- Home |

- Search Results |

- ‘This book saved my life’: How The Boy, The Mole, The Fox and The Horse became a publishing phenomenon

‘This book saved my life’: How The Boy, The Mole, The Fox and The Horse became a publishing phenomenon

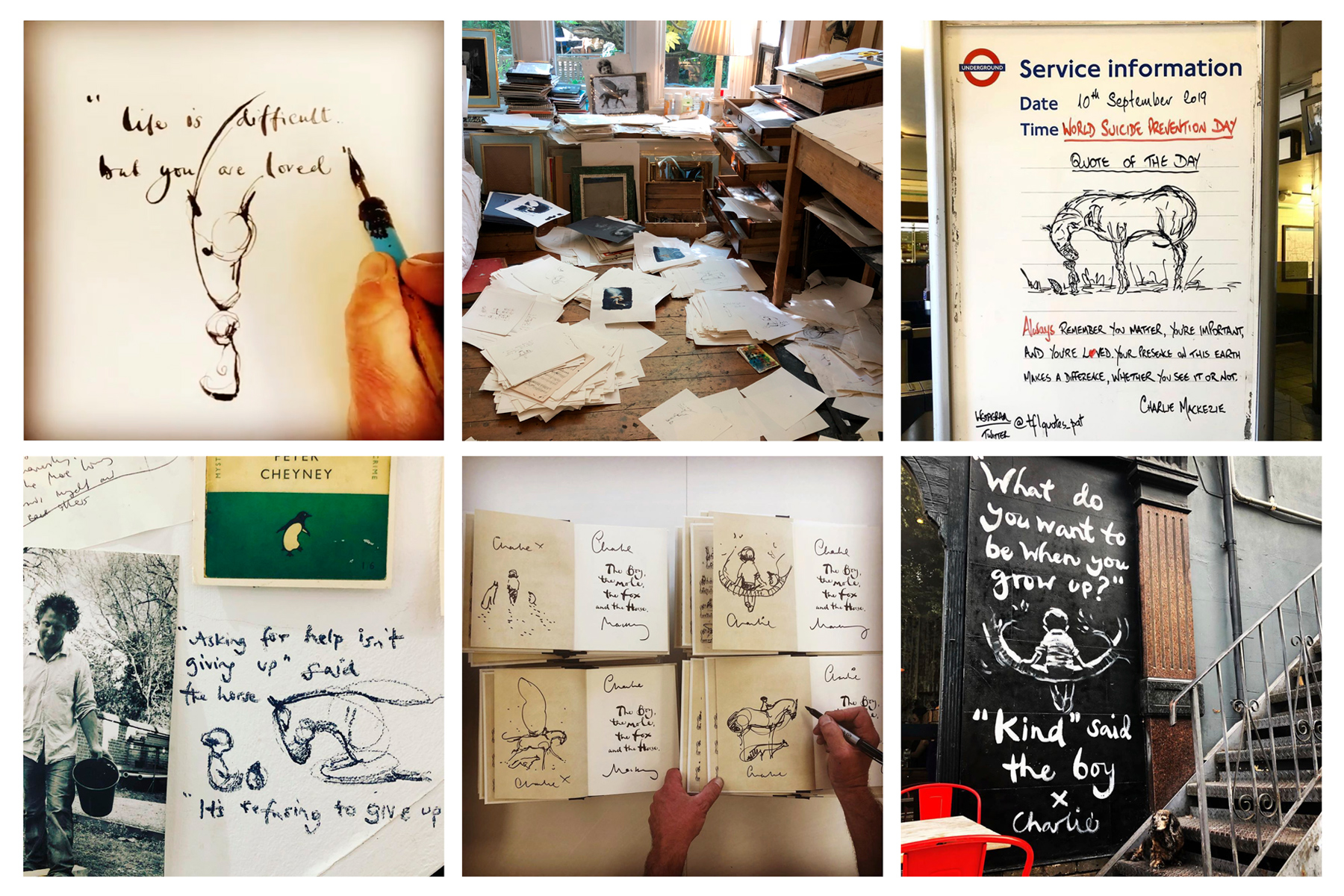

Two years after its release, artist Charlie Mackesy's quiet picture book has captured the shared longing of our troubled times. Alice Vincent reports on how it came to be, and what it means to its thousands of fans.

Three years ago, Charlie Mackesy uploaded a drawing of a boy and a mole to his Instagram account. The boy looks young, barely a toddler, barely the size of the mole, and the mole looks slightly concerned; it adds to the cuteness. ‘Tales from the underground. Another mole day I think,’ the artist captioned it.

The response was warm. Someone commented that the image took them ‘right back to the feel of my own storybook childhood’, another joked that the boy and the mole were discussing politics. What nobody realised, then, was that this was the start of what would become the surprise hit of the year. Two years after release, and Mackesy's book is the longest-running Sunday Times hardback chart-topper to date.

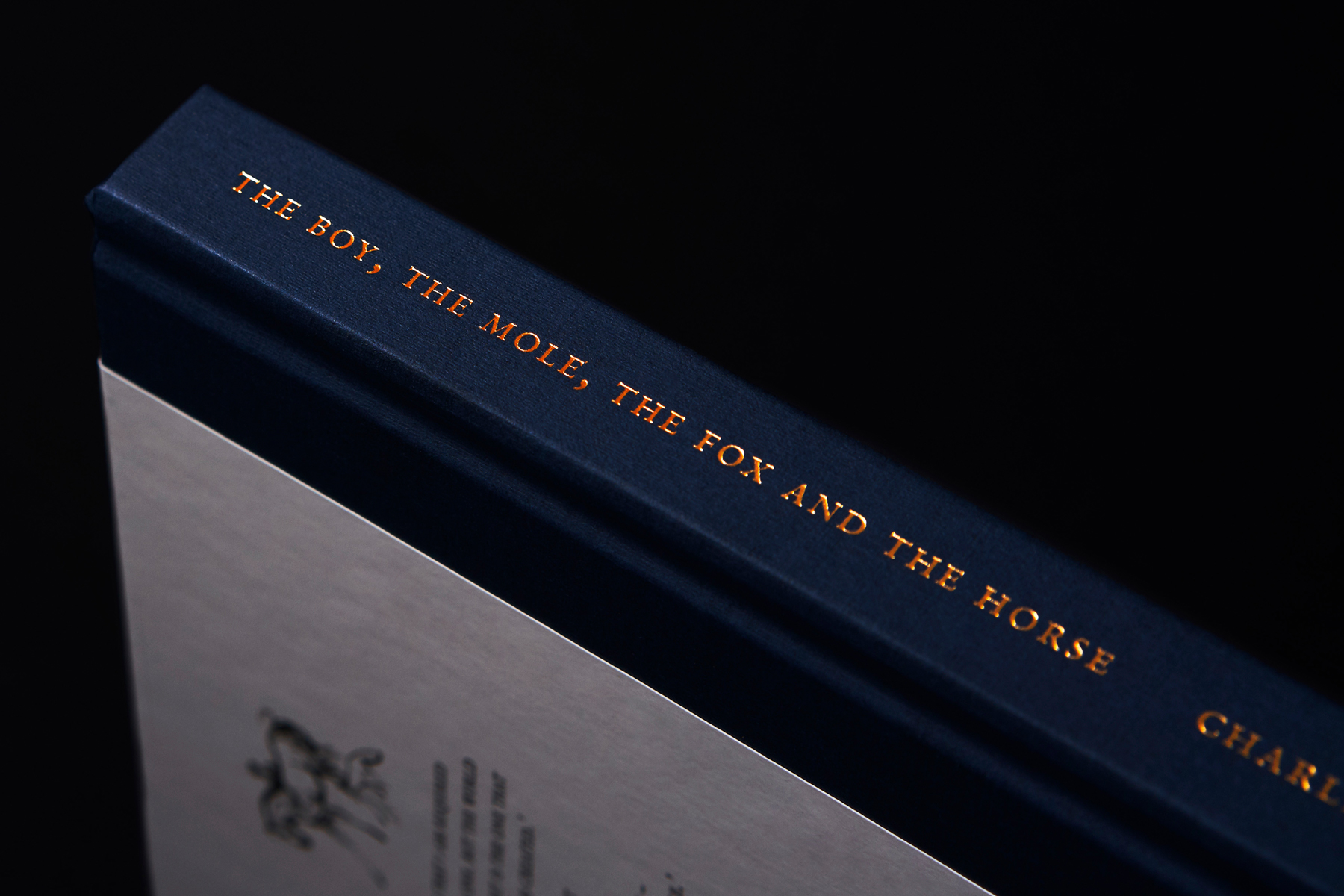

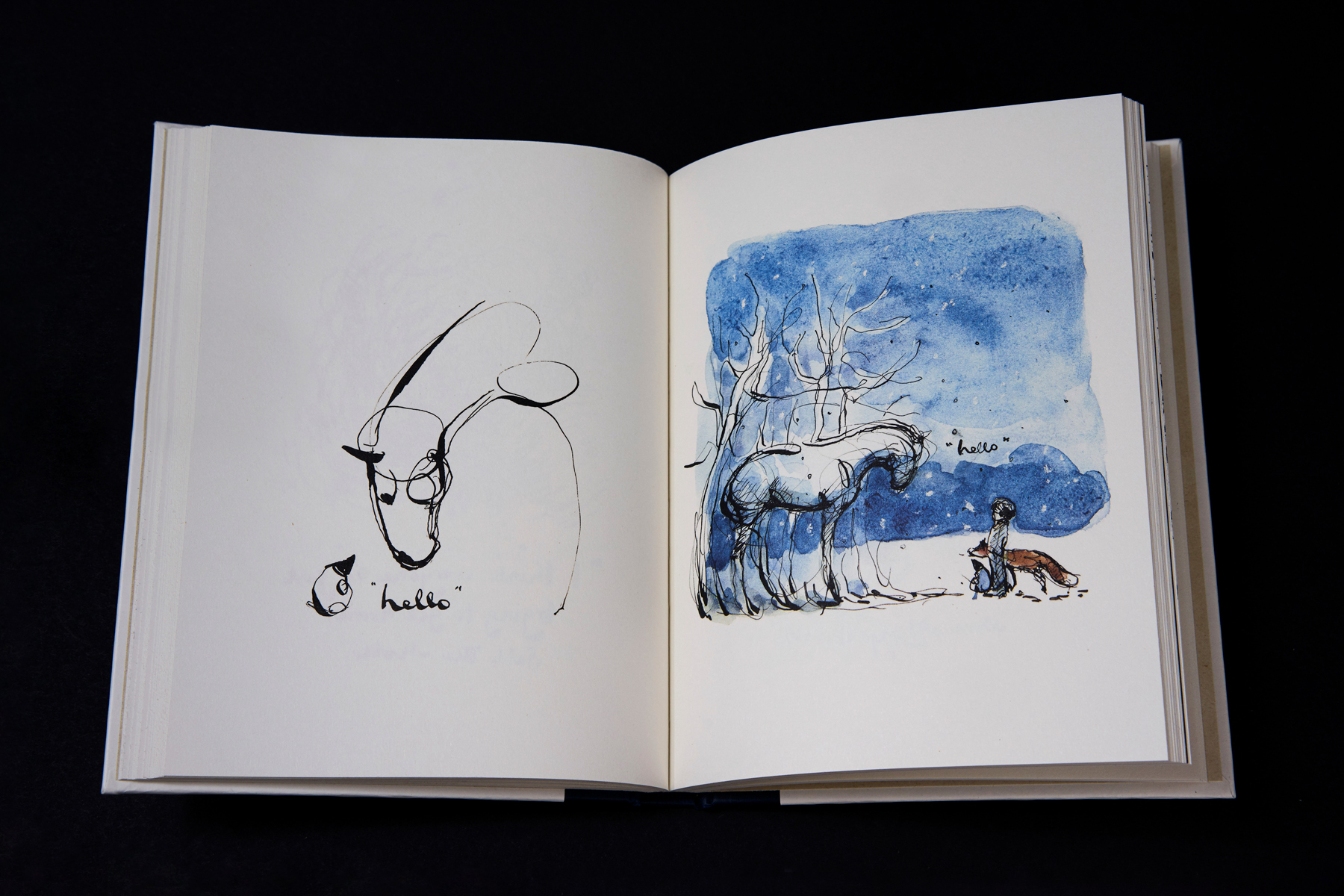

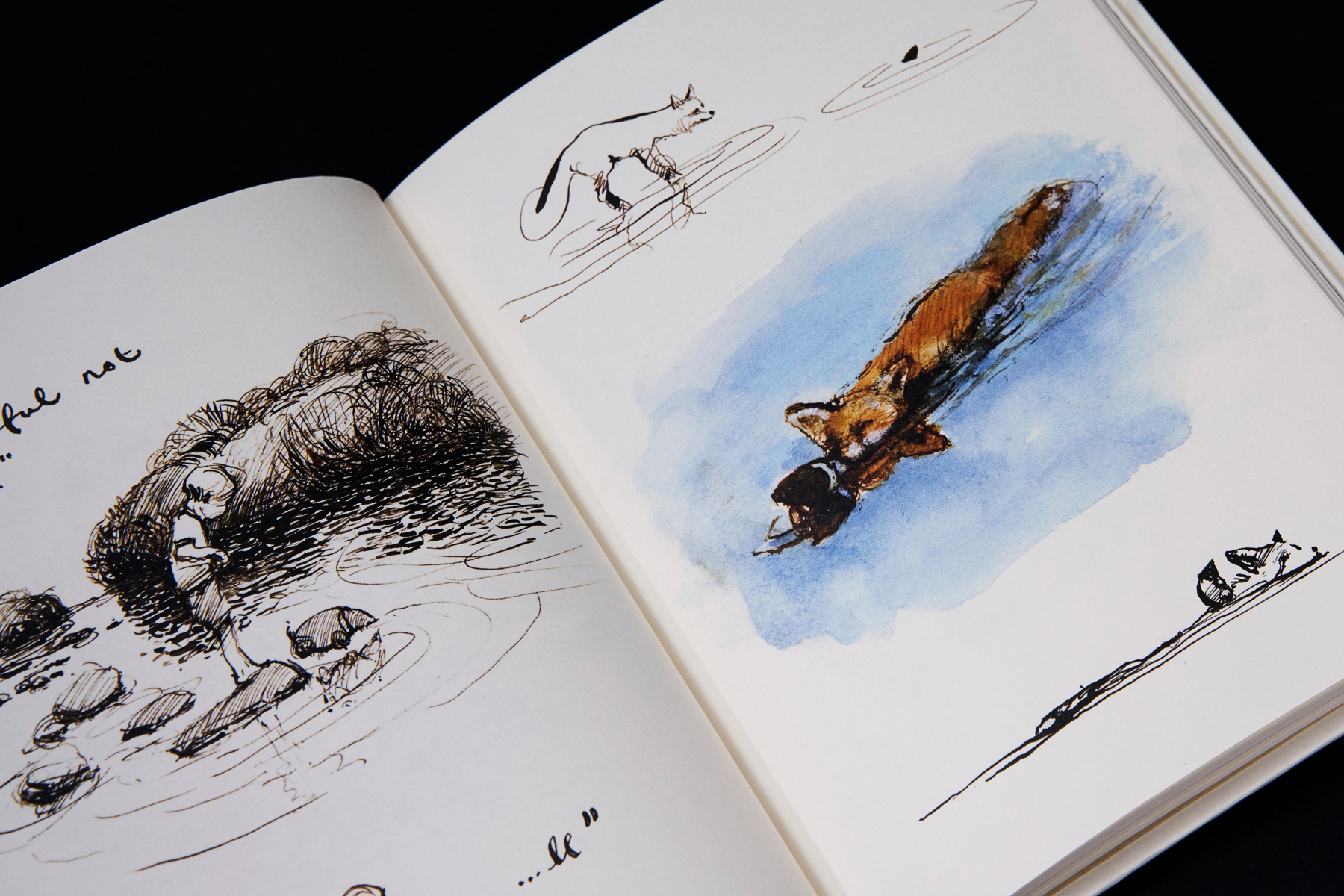

The Boy, The Mole, The Fox and The Horse isn’t a conventional picture book. Rather than a linear narrative, it’s a collection of quiet musings and conversations. The four titular characters meet one another and share each other’s confidence. It’s not aimed at any clear audience, and works as well for eight-year-olds as it does octogenarians. And yet, in the final dark months of 2019, the tremulous beginning of 2020 and the swirling chaos of the pandemic year, it offered hope to hundreds of thousands of people.

'We had to hire extra drivers to ensure copies were delivered through the night.’

It was hardly the expected outcome. The book’s editor, Laura Higginson, was introduced to Mackesy’s Instagram account by a friend, and admits to finding the drawings and words he posted there “really moving”, but The Boy, The Mole, The Fox and The Horse was still a hard sell. Mackesy had a relatively small social media following, and even the artist himself didn’t know what the plot would be. Plus, there were barely any other comparable examples in book shops.

But the team at Ebury were convinced of the book’s emotional potential. ‘Across the business, from marketing and publicity to productions, I had conversations with people who said, “Wow, what he’s doing is really beautiful,”’ Higginson tells me. Over the course of a whirlwind few months, they worked with Mackesy to capture the spirit of his work in a book.

There were late-night meetings and creative juggling as each new page was delivered. When it became clear that demand was exceeding expectations - people were pre-ordering copies in their thousands - Ebury hired extra drivers to ensure copies were delivered through the night, before the lorries immediately turned around for the next ones coming off the press.

‘The book gave me strength, encouragement, laughter in the hardest of times.’

At Mackesy’s first, sold-out signing, the queue went out the door. One woman bought 10 copies, even though she was too late to meet Mackesy and have them signed. The impact of his work was beginning to dawn on Higginson: ‘I’ve been to a few of the signings, and we’ve all ended up in tears at the end of them,’ she says. ‘The people who come queue for hours because they want to tell Charlie why they love his work and why it’s meaningful to them.’

Why Mackesy, and why his band of creatures? The artist’s name wasn’t well-known - even now, he could walk down the street and not be recognised. But his work was having an undeniable impact. While the book was being made, Mackesy’s now-recognisable painting, in which the Boy asks the Horse what the bravest thing he’s ever said, and the Horse replies, ‘help’, was being put on notice boards in schools, prisons and hospitals.

Mackesy’s drawings and words, which encouraged kindness and support, found their way onto the sides of buildings; people were getting his characters tattooed on their bodies.

People have found The Boy, The Mole, The Fox and The Horse a balm and an uplift. Lynsey Ritchie was given the book when she was half-way through 15 rounds of chemotherapy treatment for breast cancer. ‘It just touched a nerve,’ she tells me. ‘It was so refreshingly simple, uncomplicated and fresh.’

Ritchie says the book continues to help on her healing journey, and she finds herself reaching for it often. ‘It’s as if [Mackesy] manages to put into words all the jumbled thoughts I am carrying in my head and jumbled feelings in my heart,’ she says. ‘It has given me strength, encouragement, laughter and a voice in the hardest of times.’

John Fish, another reader, tells me the book has saved his life. He was experiencing suicidal thoughts having been signed off work after suffering from years of workplace harassment, but remembered the messages of Mackesy’s paintings at his 2018 exhibition. Fish cites two of the most popular images, in which the Horse and the Boy cite the power of asking for help. ‘I held those two pages [of the book] very close during the darkest moments of my life,’ Fish says.

‘Readers no longer needed the disasters explaining to them, they needed a hug.’

What we read in times of national and global turbulence can be telling. In the late-2010s, Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens experienced an unlikely sales boom, becoming a poster-child for the broader boom in high-minded, serious non-fiction that helped readers navigate a world that seemed increasingly besieged by political turmoil and climate change.

Fast-forward a few years to the end of the decade and the landscape had taken a palpable turn for the worse: beyond a global pandemic, there were threats of nuclear conflict, the #MeToo movement, the uncertainty of Brexit, international flooding and forest fires and, on a more intimate scale, a vehemently partisan social media and the disconcerting impact of online surveillance and security. Readers no longer needed the disasters explaining to them, they needed a hug.

And what The Boy, The Mole, The Fox and The Horse undoubtedly offers is comfort. Macksey’s book has racked up more than 83,000 reviews on Amazon.com, and thousands of reviews, many of them heartfelt, many of them similarly inspired. ‘I have felt quite fragile lately and this book filled me with hope’; ‘a companion to help me through all it is to be a living being in this life’; ‘it is a slice of calm in this hectic and mad world’ and ‘I've felt more at peace today having read it than I have for such a very long time’. Mackesy’s online reviewers suggest that his book is a touchstone to be returned to - they say they keep it on their bedside table for that very reason - and several compare his illustrations and outlook to that of A.A. Milne’s Winnie the Pooh books, which were originally illustrated by E.H. Shepard.

‘There are a couple of Mackesy’s pictures which are very much tributes to Shepard,’ agrees Peter Hunt, Professor Emeritus in English and Children's Literature at Cardiff University, who points out that The Boy, The Mole, The Fox and The Horse conjures the same notion of a golden world of childhood that Milne’s Pooh books did so well.

But the parallels between The Boy, The Mole, The Fox and The Horse and Winnie the Pooh extend beyond their illustrations. Like Mackesy’s debut, Milne’s first Pooh book was also released at a time of global upheaval. ‘It hit the mood when it was written,’ says Hunt. ‘It was 1926, people were back from the cataclysm of war, and what was needed was literature that was safe and comforting. Hundred Acre Wood was a very safe world, and the creatures in it were reassuring. This is what the book sold on. And it sold massively.’

Hunt also cites Jonathan Livingston Seagull, written by Richard Bach, as a similar publishing phenomenon that struck the right tone and the right time, and flew. A picture book (photographs, not illustrations) aimed at adults, it followed the philosophy of a seagull that clamours for a higher plane of living. Emerging as a magazine column in the late Sixties, by the early Seventies the book version was a US best-seller. In the midst of the disenchantment and loss of the Vietnam War, Jonathan Livingston Seagull offered a notion of self-fulfilment that gave its millions of readers hope.

As with Mackesy’s book, Bach’s baffled booksellers - would it sit in the children’s section, with the philosophy books, or even under nature? His publisher suggested it belonged next to the tills, which is exactly where you’ll find The Boy, The Mole, The Fox and The Horse in most shops.

It’s worth noting that the successes of Milne, Bach and Mackesy are rare, taking place in the 1920s, 1970s and 2020s, respectively (it’s intriguing that Pooh’s popularity dimmed in the relative prosperity of the 1950s and ‘60s). In each era, this cup-of-cocoa literature provided sanctuary from the chaos beyond their covers.

While Milne created safety and Bach spirituality, Mackesy has explored even simpler notions - and ones that, sadly, feel increasingly scarce in our online, divided lives. Love, hope, friendship and the courage of asking for help resonate deeply at a time where mental health can’t be taken for granted and kindness seems out of reach. The Boy, The Mole, The Fox and The Horse may not be able to save the world’s problems, but it has reminded thousands of people of the qualities that can.