- Home |

- Search Results |

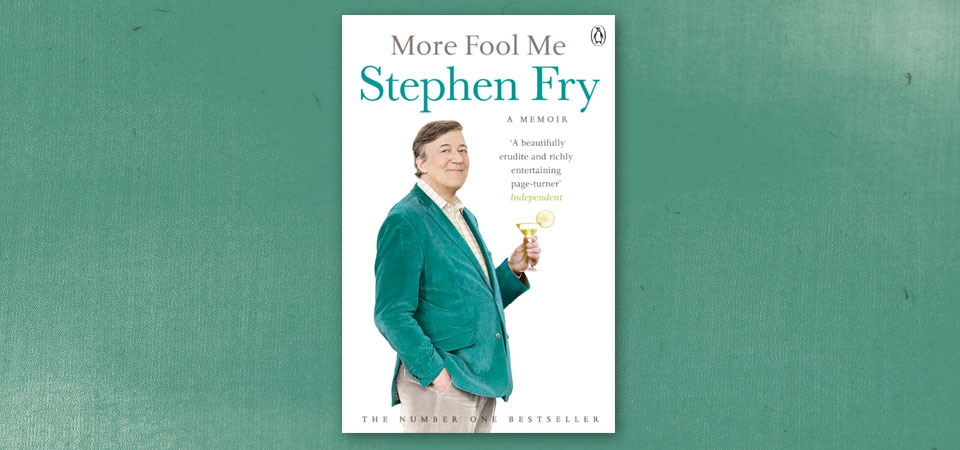

- More Fool Me by Stephen Fry

There is nothing very appealing about showbusiness memoirs. A linear chronology of successes, failures and blind ventures into new fields is dull enough. And then there is the problem of how to approach descriptions of collaborators and contemporaries:

'She was adorable to work with, incredibly funny and always intensely cheerful and considerate. To know her was to worship her.'

'I was captivated by his talent, how marvellously he shone in everything he did. There was a luminosity, a kind of transcendence.’

'She always had time for her fans, no matter how persistent they were.'

'What a perfect marriage they had, and what ideal parents they were. A golden couple.'

I could be describing actors, TV show presenters or producers with total accuracy, leaving out only their serial polygamies, chronic domestic abuse, violent orgiastic fetishes and breathtaking assaults on the bottle, the powders and the pills.

Is it right of me to be searingly, bruisingly honest about the lives of others? I am quite prepared to be searingly, bruisingly honest about my own, but I just don't have it in me to reveal to the world that, for example, producer Ariadne Bristowe is an aggressively vile, treacherous bitch who regularly fires innocent assistants just for looking at her the wrong way; or that Mike G. Wilbraham has to give a blowjob to the boom operator while finger-banging the assistant cameraman before he is prepared so much as to think about preparing for a scene. All these things are true, of course, but fortunately Ariadne Bristowe doesn't exist and neither does Mike G. Wilbraham. OR DO THEY?

The actor Rupert Everett in his autobiographical writings manages to be caustic in what you might call a Two Species manner: bitchy and catty. The results are hilarious, but I am far too afraid of how people view me to be able to write like that. Very happy to recommend both his volumes of autobiography/memoir to you, however: Red Carpets and Other Banana Skins and The Vanished Years. Ideal holiday or Christmas reading.

So I now must consider how to present to you this third edition of my life. It must be confessed that this book is an act as vain and narcissistic as can be imagined: the third volume of my life story?

There are plenty of wholly serviceable single-volume lives of Napoleon, Socrates, Jesus Christ, Churchill and even Katie Price. So by what panty-dribbling right do I present a weary public with yet another stream of anecdote, autobiography and confessional?

The first I wrote was a memoir of childhood, the second a chronicle of university and the lucky concatenation of circumstances that led to my being able to pursue a career in performing, writing and broadcasting. Between the end of that second book and this very minute, the minute now that I am using to type this sentence, lies over a quarter of a century of my milling about on television, in films, on radio, writing here and there, getting myself into trouble one way or another, becoming a representative of madness, Twitter, homosexuality, atheism, annoying ubiquity and whatever other kinds of activity you might choose to associate with me.

I am making the assumption that in picking up this book you know more or less who I am. I am keenly aware – how could I not be? – that if one is in the public eye then people will have some sort of view. There are those who thoroughly loathe me. Even though I don’t read newspapers or receive violent abuse in the street, I know well enough that there are many members of the British public, and I daresay the publics of other countries, who think me smug, attention-seeking, false, complacent, self-regarding, pseudo-intellectual and unbearably irritating: diabolical. I can quite see why they would. There are others who embarrass me charmingly by their wild enthusiasm; they shower me with praise and attribute qualities to me that seem almost to verge on the divine.

I don't want this book to be riddled with too much self-consciousness. There is a lot to say about the end of the 1980s and early 1990s, and you may find the way I go about it to be meandering. I hope a chronology of sorts will emerge as I bounce from theme to theme. There will inevitably be anecdotes of one kind or another, but it is not my business to tell you about the private lives of others, only of my own. I consider myself incompetent when it comes to the business of living life.

Maybe that is why I am committing the inexcusable hubris of offering the world a third written autobiography. Maybe here is where I will find my life, in this thicket of words, in a way that I never seem to be able to do outside the bubble I am in now as I write. Me, a keyboard, a mouse, a screen and nothing else. Just loo breaks, black coffees and an occasional glance at my Twitter and email accounts. I can do this for hours all on my own. So on my own that if I have to use the phone my voice is often hoarse and croaky because days will have passed without me speaking to a single soul.

So where do we go from here?

Let's find out.

Catch-up

I have a recurring dream. The doorbell sounds at three in the morning. I struggle out of bed and press the entryphone button.

'Police, sir. May we come in?' 'Of course, of course.'

I buzz them in. A series of charges that I cannot quite make out are chanted at me like psalms. I am arrested and cuffed. It is all very hurried and sudden but entirely good-natured. One of the policemen asks for a photograph with me.

We cut, as dreams so cinematically do, to a courtroom, where a much less sympathetic judge sentences me to six months’ imprisonment with hard labour. He is disgusted that someone who should know so much better could have committed so foolish a crime and present so ignoble an example to the young, impressionable people who might errantly look up to him. The judge wishes the sentence could be longer but he must abide by the guidelines laid down by statute.

To the sound of mingled cheers and jeers I am conducted down to the police cells and into the back of a van, which is delightfully decorated and exquisitely supplied with crystal, ice buckets and an amazing array of alcoholic drinks.

'Might as well get lashed, Stephen. Last drinks you’re going to have for some while.'

I'm at the prison. All the convicts have turned out to greet me. Their welcome is deafening and not in the least threatening.

A vast dining hall. I sit to eat in a huge wide shot like Cody Jarrett as played by James Cagney in White Heat. And then we see me in midshot, as cool and unruffled as Tim Robbins's ageless Andy Dufresne, taking my tray to the table.

It is clear that I am not in the joint for some appalling sexual or financial misdemeanour that will cause me to be beaten and tormented by my fellow convicts. I have done something that is wrong, that is disapproved of by 'society' yet which is tolerated with amusement by criminals and even police officers.

Nobody lets me see the newspapers. They will only upset me, I am told. It is all very strange.

Friends visit me. Always staying the other side of the bars. Hugh and Jo Laurie. Kim Harris, my first lover. My literary agent Anthony and my theatrical agent Christian. My sister and PA Jo. There is something they are not telling me, but I am comfortable in prison and feel sorry for them, having to leave and return to the world of bustle and business.

I am in the corridor cleaning the floor with an electric polisher. It has two rotating discs with gently abrasive pads press-studded to the base, and I enjoy holding it like a pneumatic drill, feeling its power under me, how I have to keep it from flying free of my grip as it pulls like an eager dog at the leash. The floor comes up in a glossy shine. This is the life.

An old lag walks up to me, coughing on his tightly rolled-up cigarette, which wags up and down as he speaks. He has seen a letter in the governor’s office, which he Pledges and tidies daily. My sentence is to be extended. I will never leave.

I take the news well. Very well.

I wake up, or the dream peters out or merges into something strange and silly and different.

It is easy to attempt a little oneiromancy here. My real life is a prison, so a real prison would be an escape. That would be the one-line pitch, as they say in Hollywood. I am one who, like so many Britons of a certain class and era, was born to institutions. School houses merge into Oxbridge colleges which merge into Inns of Court or the BBC as it was or into regiments or ships of the line or into one of the two Houses of Parliament or into the Royal Palaces or into Albany or the clubs of Pall Mall and St James’s. All very male, all very Anglo-Saxon (a few Jews allowed from time to time – it is vulgar to be racially obsessed), all very cosy, absurd and out of date. If you really want to have a look at this world in its last hurrah just before I was born then you should read the first eight or nine chapters of Moonraker, a Bond novel, but with an opening that is simultaneously hilarious, fantastically observed, droolworthily aspirational and skin-pricklingly suspenseful.

I observed of myself in my second book of memoirs, The Fry Chronicles, and earlier in my first, Moab is my Washpot, that I seem always to be obsessed with belonging. Half of me, I wrote in Moab, yearns to be part of the tribe; the other half yearns to be apart from the tribe. All the clubs I belong to – six so-called gentleman’s clubs and goodness knows how many more Soho-style media watering-holes – are vivid testament to a soul searching for his place in British society. Maybe prison is the ultimate club for people like me. 'That's institootionalized,' as Morgan Freeman’s Red puts it in The Shawshank Redemption, the world's favourite film.

I am wary of interpretations. I refuse to interpret my life and its motives because I am not qualified. You may choose to do so. You may find me and my history repugnant, fascinating, indicative of an age now long gone, typical of a breed whose time is up. There are all kinds of ways of looking at me and my story.

If you want to bore someone, tell them your dreams. I seem to have got off on the wrong foot. I plead forgiveness for, while I would not claim that there is anything experimental about this memoir, I would ask you to be ready for a flitting backwards and forwards in time. The experience of writing about this period in my life has had some of the qualities of a dream: unexpected, freakish, disgusting, frightening, incredible and at one and the same time crystal clear and maddeningly occluded.

It is my job, I suppose in this far from divine comedy, to be Virgil to your Dante, guiding you as straightforwardly and tenderly as I can through the circles of my particular hell, purgatory and heaven. In the following pages I will try to be as truthful as I can; I will leave interpretation and, generally speaking, motivation, to you.