- Home |

- Search Results |

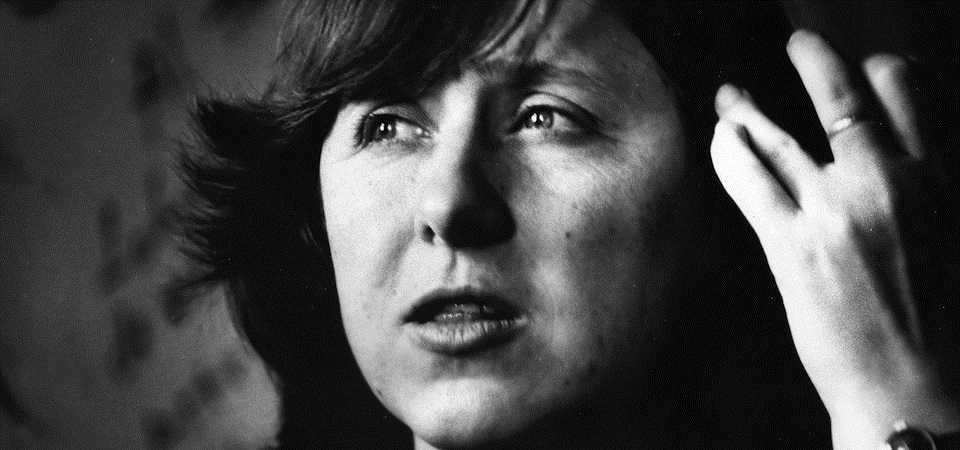

- On the Battle Lost by Svetlana Alexievich

On the Battle Lost by Svetlana Alexievich

Starting out as a journalist, Alexievich developed her own non-fiction genre, which brings together a chorus of voices to describe a specific historical moment. This is an extract from the lecture she delivered after winning the Nobel Prize for literature in 2015, along with the opening of her book, Chernobyl Prayer

I do not stand alone at this podium ... There are voices around me, hundreds of voices. They have always been with me, since childhood. I grew up in the countryside. As children, we loved to play outdoors, but come evening, the voices of tired village women who gathered on benches near their cottages drew us like magnets. None of them had husbands, fathers or brothers. I don't remember men in our village after World War II: during the war, one out of four Belarusians perished, either fighting at the front or with the partisans. After the war, we children lived in a world of women. What I remember most, is that women talked about love, not death. They would tell stories about saying goodbye to the men they loved the day before they went to war, they would talk about waiting for them, and how they were still waiting. Years had passed, but they continued to wait: 'I don't care if he lost his arms and legs, I'll carry him.' No arms ... no legs ... I think I've known what love is since childhood ...

Here are a few sad melodies from the choir that I hear ...

First voice:

'Why do you want to know all this? It's so sad. I met my husband during the war. I was in a tank crew that made it all the way to Berlin. I remember, we were standing near the Reichstag – he wasn't my husband yet – and he says to me: "Let's get married. I love you." I was so upset – we'd been living in filth, dirt, and blood the whole war, heard nothing but obscenities. I answered: "First make a woman of me: give me flowers, whisper sweet nothings. When I'm demobilized, I'll make myself a dress." I was so upset I wanted to hit him. He felt all of it. One of his cheeks had been badly burned, it was scarred over, and I saw tears running down the scars. "Alright, I'll marry you," I said. Just like that ... I couldn't believe I said it ... All around us there was nothing but ashes and smashed bricks, in short – war.'

Second voice:

'We lived near the Chernobyl nuclear plant. I was working at a bakery, making pasties. My husband was a fireman. We had just gotten married, and we held hands even when we went to the store. The day the reactor exploded, my husband was on duty at the firе station. They responded to the call in their shirtsleeves, in regular clothes – there was an explosion at the nuclear power station, but they weren't given any special clothing. That's just the way we lived ... You know ... They worked all night putting out the fire, and received doses of radiation incompatible with life. The next morning they were flown straight to Moscow. Severe radiation sickness ... you don't live for more than a few weeks ... My husband was strong, an athlete, and he was the last to die. When I got to Moscow, they told me that he was in a special isolation chamber and no one was allowed in. "But I love him," I begged. "Soldiers are taking care of them. Where do you think you're going?" "I love him." They argued with me: "This isn't the man you love anymore, he's an object requiring decontamination. You get it?" I kept telling myself the same thing over and over: I love, I love ... At night, I would climb up the fire escape to see him ... Or I'd ask the night janitors ... I paid them money so they'd let me in ... I didn't abandon him, I was with him until the end ... A few months after his death, I gave birth to a little girl, but she lived only a few days. She ... We were so excited about her, and I killed her ... She saved me, she absorbed all the radiation herself. She was so little ... teeny-tiny ... But I loved them both. Can you really kill with love? Why are love and death so close? They always come together. Who can explain it? At the grave I go down on my knees ...'

Third Voice:

'The first time I killed a German ... I was ten years old, and the partisans were already taking me on missions. This German was lying on the ground, wounded ... I was told to take his pistol. I ran over, and he clutched the pistol with two hands and was aiming it at my face. But he didn't manage to fire first, I did ...

It didn't scare me to kill someone ... And I never thought about him during the war. A lot of people were killed, we lived among the dead. I was surprised when I suddenly had a dream about that German many years later. It came out of the blue ... I kept dreaming the same thing over and over ... I would be flying, and he wouldn't let me go. Lifting off ... flying, flying ... He catches up, and I fall down with him. I fall into some sort of pit. Or, I want to get up ... stand up ... But he won't let me ... Because of him, I can't fly away ...

The same dream ... It haunted me for decades ...

I couldn't tell my son about that dream. He was young – I couldn't. I read fairy tales to him. My son is grown now – but I still can't ..."

Translated by Jamey Gambrell.

Read on here.

Chernobyl Prayer

A Lone Human Voice

I don’t know what to tell you about. Death or love? Or is it the same thing. What should I tell you about?...

We were just married. We’d still hold hands walking down the street, even if we were going to the shops. We were together the whole time. I used to say, ‘I love you.’ But I couldn’t imagine just how much I loved him. I had no idea. We lived in the hostel for the fire station where he worked. On the first floor. Lived there with three other young families. We all shared a kitchen. The fire engines were below us, at ground level. Red fire engines. It was his work. I always knew where he was, what he was up to. In the middle of the night, I heard some noise. There was shouting. I looked out the window. He saw me and said, ‘Shut all the windows and go back to bed. The power station’s on fire. I won’t be long.’

I never saw the explosion itself. Only the flames. Everything was kind of glowing. The whole sky ... There were these tall flames. Lots of soot, terrible heat. I was waiting and waiting for him. The soot was from burning bitumen, the roof of the power plant was covered in it. He told me later it was like walking on hot tar. They beat back the fire, but it was creeping further, climbing back up. They kicked down the burning graphite. They didn’t have their canvas suits on, they left just in the shirts they were wearing. Nobody warned them. They were just called out to an ordinary fire.

It was four o’clock. Five o’clock. Six o’clock. At six, we were planning to visit his parents. We were going to plant potatoes. From our town of Pripyat to Sperizhye, the village where his parents lived, was forty kilometres. He loved planting and tilling. His mum often spoke of how they never wanted him to leave for the town. They even built him a new house. He was called up, served in the Moscow firefighting troops, and when he came back, it was only the fire brigade for him! There was nothing else he wanted to do. (She falls silent.)

Sometimes it’s like I’m hearing his voice. Like he’s alive ... Even the photos don’t get at me the way his voice does. But he’s never calling me. Even in the dreams. It’s always me calling him.

Seven in the morning. At seven, they told me he was in the hospital. I rushed over, but there was a police cordon round the hospital, they weren’t letting anyone in. Only the ambulances were let through. The police were warning us not to go near the ambulances. The Geiger counters were going berserk! I wasn’t the only one. All the wives rushed over, everyone whose husband had been at the power plant that night. I ran to look for my friend. She was a doctor at the hospital. I grabbed her by her white coat as she was coming out of an ambulance. ‘Let me in there!’ ‘I can’t! He’s in a terrible state. They all are.’ I wouldn’t let go of her: ‘I just want to look at him.’ ‘All right, then,’ she says, ‘but we’ll have to be quick. Just fifteen or twenty minutes.’ So I saw him. He was all puffed up and swollen. His eyes were almost hidden. ‘He needs milk, lots of it!’ my friend told me. ‘They need to have at least three litres of milk.’ ‘But he doesn’t drink milk.’ ‘Well, he will now.’ Later, lots of the doctors and nurses in the hospital, and especially the orderlies, came down sick. They died. But back then, nobody knew that would happen.

At ten in the morning, Shishenok, one of the plant’s operators, died. He was the first. On that first day. We heard another was trapped under the rubble: Valery Khodemchuk. They never got him out. He was buried in concrete. We didn’t know at that time they were only the first.

I said, ‘Vasya, what should I do?’ ‘Get out of here! Just go away! You’re having a baby.’ I was pregnant. But how could I leave him? He begged me: ‘Get out! Save the baby!’ ‘First I need to bring you some milk, and then we’ll see.’

My friend Tanya Kibenok came rushing over. Her husband was in the same ward. She was with her father. He’d brought her by car. We jumped in and drove to the nearest village to get fresh milk. It was three kilometres out of town. We bought lots of three-litre jars of milk. We got six, so there’d be enough for everyone. But the milk just made them violently sick. They kept losing consciousness all the time. They were put on drips. For some reason, the doctors kept insisting they’d been poisoned by gas, no one said anything about radiation. And the town filled up with these army vehicles, they blocked off all the roads. There were soldiers everywhere. The local trains and the long-distance ones all stopped running. They were washing down the streets with some sort of white powder. I was worried about how I’d get to the village the next day to buy fresh milk. Nobody said anything about radiation. It was just the soldiers who were wearing respirators. People in town were taking bread from the shops, buying loose sweets. There were pastries on open trays. Life was going on as normal. Only they were washing down the streets with that powder.

In the evening, they wouldn’t let us into the hospital. There was a whole sea of people. I stood outside his window, he came over and was shouting something to me. Shouting desperately! Somebody in the crowd heard him: they were being moved to Moscow that night. The wives all huddled together. We decided we were going with them. ‘Let us see our husbands!’ ‘You can’t keep us out!’ We fought and scratched. The soldiers were pushing us back, there were already two rows of them. Then a doctor came out and confirmed they were being flown to Moscow, but he said we needed to bring them clothes – what they were wearing at the power station had all got burned. There were no buses by then, so we ran, all the way across town. We came running back with their bags, but the plane had already gone. They had done it to trick us. So we wouldn’t shout and weep.

The whole street was covered in white foam. We were walking over it, cursing and crying.

It was night. On one side of the street were buses, hundreds of them (they were already preparing to evacuate the town), on the other side were hundreds of fire engines. They’d brought them in from everywhere. The whole street was covered in white foam. We were walking over it, cursing and crying.

On the radio, they announced: ‘The town is being evacuated for three to five days. Bring warm clothes and tracksuits. You’ll be staying in the forests, living in tents.’ People even got excited: a trip to the countryside! We’ll celebrate May Day there. That’ll be something new! They got kebabs ready for the trip, bought bottles of wine. They took their guitars, portable stereos. Everybody loves May Day! The only ones crying were the women whose husbands were ill.

I don’t remember how we got there. It was like I woke up only when I saw his mother: ‘Mum, Vasya’s in Moscow! They took him away in a special plane!’ We finished planting the vegetable plot with potatoes and cabbage, and a week later they evacuated the village! Who could have guessed? Who knew back then? That evening, I began throwing up. I was six months pregnant. I was feeling so awful. At night, I dreamed he was calling my name. While he was still alive, I’d hear him in my dreams: ‘Lyusya! My Lyusya!’ But after he died, he never called my name. Not once. (She cries.) I got up in the morning with the idea of going to Moscow on my own. ‘Where are you off to in your state?’ his mother asked, so upset. They decided his father should get packed too: ‘He’ll go with you.’ They took out all their savings. All their money.

I don’t remember the trip. It’s gone from my memory. In Moscow, we asked the first policeman we found for the hospital the Chernobyl firemen were in, and he told us. I was quite surprised, because they had been scaring us, saying, ‘It’s a state secret, top secret.’

It was Hospital No. 6, at Shchukinskaya metro station.

It was this special radiation hospital and you couldn’t get in without a permit. I slipped the receptionist some money, and she told me to go on in. She told me which floor. I asked someone else, I was begging them. Then there I was, sitting in the office of Dr Guskova, the head of the radiation department. At the time, I didn’t know her name, couldn’t hold anything in my mind. All I knew was I had to see him. Had to find him.

First thing she asked me was: ‘You poor, poor thing. Have you got children?’

How could I tell her the truth? I realized I needed to hide my pregnancy. Or they wouldn’t let me see him! A good thing I was skinny, you couldn’t tell by looking at me.

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘How many?’

I thought: ‘I’ve got to say two. If I say one, they still won’t let me in.’

‘A boy and a girl.’

‘As you’ve got two, you probably won’t be having any more babies. Now listen: the central nervous system is severely affected, the bone marrow too.’

‘So, all right,’ I thought, ‘he’ll become a bit excitable.’

‘And another thing: if you start crying, I’ll send you straight out. No hugging or kissing. You mustn’t get close. I’ll give you half an hour.

But I knew I wouldn’t be leaving this place. I wasn’t going anywhere without him. I swore it to myself!

I went in. They were sitting on the bed, playing cards and laughing.

‘Vasya!’ they called to him.

And he turns round and says, ‘Oh no, guys, I’m done for! She’s even found me here!’

He looked so funny, had these size forty-eight pyjamas on, though he was a fifty-two. The sleeves and legs were too short. But the swelling had gone down on his face. They were giving them these fluids by a drip.

‘What’s all this, eh? Why are you done for?’ I asked.

He wanted to hug me.

‘Sit right back down.’ The doctor wouldn’t allow him near me.

‘No cuddling here.’

Somehow we turned it into a joke. At that point everyone came running over, even from the other wards. All our guys from Pripyat. Twenty-eight of them had been flown here. They wanted to know what was happening back home. I told them they’d begun an evacuation, the whole town was being moved out for three to five days. The guys went quiet. There were two women as well. One had been on reception duty the day of the accident, and she started crying. ‘Oh my God! My children are there. What will happen to them?’

I wanted to be alone with him, just for a minute or two. The guys picked up on it, each made some excuse and they went out into the corridor. Then I hugged him and kissed him. He backed away.

‘Don’t sit near me. Use the chair.’

‘Oh, all this is silly,’ I told him, waving it off. ‘Did you see where the blast was? What happened? You were the first ones there.’

‘Most likely sabotage. Somebody must have done it deliberately. That’s what all the guys reckon.’

It was that everyone was saying. What they thought at the time.

When I came the next day, they were all in separate rooms. They were strictly forbidden to go out in the corridor or mill about with each other. So they tapped on the walls: dot-dash, dot-dash, dot. The doctors explained that each person’s body reacts differently to radiation exposure, and what one person can take would be too much for another. Inside their rooms, even the walls were off the scale. To the left, the right and the floor below they moved everyone out, not one patient stayed. The floors above and below them were empty.

I stayed three days with some friends in Moscow. They told me to take a pot, a bowl, to help myself, not be shy. Amazing people! I made turkey broth for six men. Six of our guys. Firemen on the same shift, the ones on duty that night: Vashchuk, Kibenok, Titenok, Pravik and Tishchura. I picked up toothpaste, toothbrushes and soap for them all at the shops. They had none of that in the hospital. I bought them some little towels. Looking back, I’m amazed at my friends – of course they were frightened, they had to be, what with all the rumours flying, but they still said to take what I needed. They asked how he was doing, how all of them were doing. Would they live? Would they . . . (She is silent.) At the time, I met so many good people, can’t even remember them all. The whole world shrank to a dot. There was just him. Nothing but him . . . I remember one orderly, she taught me: ‘Some illnesses are incurable. You just have to sit and stroke their hands.’

Early in the morning, I’d set out to the market, then back to my friends to boil up some broth. Grated everything, chopped it fine, ladled it out into portions. One man asked me to bring him an apple. I had six half-litre jars to carry to the hospital. Always for six men! Stayed there till the evening. And then back again to the other end of town. How long could I keep it up? But on the fourth day, they told me I could stay in the hotel for medical staff in the hospital grounds. My God, what a blessing!

‘But there’s no kitchen. How will I cook for them?’

‘You won’t need to do any more cooking. Their stomachs have started rejecting food.’

He began changing: every day, I found a different person. His burns were coming to the surface. First these little sores showed up inside his mouth and on his tongue and cheeks, then they started growing. The lining of his mouth was peeling off in these white filmy layers. The colour of his face … The colour of his body … It went blue. Red. Greyish-brown. But it was all his precious, darling body! You can’t describe it! There are no words for it! It was too much to take. What saved me was how fast it was all happening, I didn’t have time to think or cry.

I loved him so much! I had no idea how badly I loved him! We were just married, couldn’t get enough of each other. We’d walk down the street and he’d grab me in his arms and spin me round. And cover me in kisses. The people passing would smile.

He spent fourteen days in the Clinic for Acute Radiation Sickness. It takes fourteen days to die.

On that first day in the hotel, they took readings from me. My clothing, bag, purse, shoes – they were all ‘scorching’. So they took the lot away from me on the spot. Even my underwear. They only left me my money. They gave me a hospital gown to put on instead, but it was a size fifty-six – I’m a forty-four – and the slippers were size forty-three, not my thirty-seven. They said I might get my clothing back, or maybe not, they doubted it could be ‘cleaned’. So I showed up looking like that. It gave him a fright: ‘My God, what’s happened to you?’

I came up with a way to cook broth. I put an electric water heater in a glass jar and threw in tiny pieces of chicken. Very finely chopped. Then someone gave me a pot. I think it was the cleaning lady or the hotel attendant. Someone gave a chopping board, which I used for cutting parsley. In that hospital gown I couldn’t go to the market, so someone bought me the parsley. But it was all a waste of time, he couldn’t even drink. Couldn’t swallow a raw egg. And I wanted to give him something tasty! As though it might help him.

I ran to the post office: ‘Please, ladies, I have to call my parents in Ivano-Frankovsk urgently. My husband is dying.’ Somehow they guessed right away where I was from and who my husband was and they put me straight through. My father, sister and brother flew to Moscow the same day. They brought me my things and some cash.

It was 9 May. He’d always said to me: ‘You have no idea how beautiful Moscow is! Specially on Victory Day, when they have the fireworks. I want to show it to you.’ I was sitting next to him in the room, he opened his eyes: ‘Is it day or night?’

‘Nine in the evening.’

‘Open the window! The fireworks will be starting!’

I opened the window. We were on the eighth floor, the whole city spread out before us! A bouquet of fire shot into the sky. ‘Wow, that’s something!’

‘I promised that I’d show you Moscow. I promised that I’d always give you flowers for every holiday.’

I turned round and he pulled three carnations from behind his pillow. He’d given some money to a nurse to buy them.

I ran over and kissed him. ‘My darling! My true love!’

He grumbled, ‘What did the doctors say? No hugging me! No kissing!’

They’d forbidden me to cuddle him or stroke him. But I lifted him and positioned him on the bed. Smoothed the bed sheets for him, took his temperature, brought the bedpan, then took it away. Wiped him down. All night long, I was close by. Watching over every move he made, every sigh.

It’s a good job it happened in the corridor and not in his room. I started feeling dizzy and grabbed on to the windowsill. A doctor was walking past, he took hold of my arm. And suddenly he asked: ‘You’re pregnant?’

‘No, no!’ I was terrified that someone would hear us.

‘Don’t pretend,’ he said, with a sigh.

I was so shaken that I didn’t manage to ask him to keep quiet.

The next day, I was called to the head of the department.

‘Why did you trick us?’ she asked harshly.

‘I had no way out. If I’d told you the truth, you’d have sent me home. It was a little white lie!’

‘What on earth have you done!’

‘But I’m by his side . . .’

‘You poor, poor thing!

Till my dying day, I’ll be grateful to Dr Guskova.

The other wives also came, but they weren’t allowed in. The mothers were with me: they let the mothers in. Vladimir Pravik’s mother kept begging God, ‘Take me instead.’

Dr Gale, this American professor. He did the bone marrow transplant. He comforted me, saying there was hope, maybe not much, but with his strong body, such a hefty guy, we still had a chance. They sent for all his family. Two sisters came from Belarus, and his brother from Leningrad, where he was serving in the army. Natasha, the younger one, was just fourteen, she was crying a lot and frightened. But her bone marrow was the best match. (She falls silent.) I’m able to talk about it now. Before, I couldn’t. I kept quiet for ten years. Ten years . . . (She is silent.)

When he found out the bone marrow would be from his little sister, he flat out refused: ‘No, I’d rather die. Leave her alone, she’s just a kid.’ His older sister, Lyuda, was twenty-eight, she was a nurse and knew what she was going into. ‘I just want him to live,’ she was saying. I watched the operation. They were lying side by side on the table. The operating theatre had a big window. It lasted two hours. When they’d finished, Lyuda was worse off than him, she had eighteen puncture holes in her chest and had a rough time coming round. And she’s in poor shape now, she’s registered disabled … Used to be this beautiful, strong woman. She never got married. So I was rushing from one ward to the other, from his bedside to hers. By then, he wasn’t in an ordinary ward, they’d put him in this special pressure chamber, behind a see-through plastic curtain, which you weren’t allowed past. It was specially equipped so you could give injections and insert catheters without having to go behind the plastic. It was all sealed off with locks and velcro, but I worked out how to open them up. I’d quietly move aside the plastic and sneak in to see him. In the end, they just put a little chair for me by his bed. He got so bad that I couldn’t leave his side. He kept calling my name: ‘Lyusya, where are you? My Lyusya!’ He called over and over. The pressure chambers for the rest of our guys were being looked after by soldiers, because the orderlies were refusing and demanding protective clothing. The soldiers took out the bedpans, they mopped the floors, changed the sheets. Took full care of them. Where had these soldiers come from? I didn’t ask. I only saw him. Nothing but him . . . And each day I’d hear: ‘This one’s died, that one’s died.’ Tishchura died. Titenok died. ‘Died …’ It was like a hammer hitting your head.