- Home |

- Search Results |

- A trip through the landscapes of communism

ZIL Palace of Culture, Moscow

Designed by the trio of Vesnin brothers – Viktor, Leonid and the avant-garde painter and set designer Alexander, this is the largest of all the Constructivist buildings of the immediate post-revolutionary era. Designed in 1930 and not finished until 1938, by which time such buildings were officially condemned, this cultural complex was built for the workers of the ZIL automobile factory, on the site of a partially destroyed monastery. Its flowing, generous spaces and its mix of facilities – library, concert hall, planetarium, cafes, crèches, among others – make it an example of what Constructivists called a 'social condenser', which would encourage a harmonious communist existence. Currently, it's carved up between a pleasant, faintly hipstery refurbishment and kitsch cafes with blaring, big-screen Russian music TV.

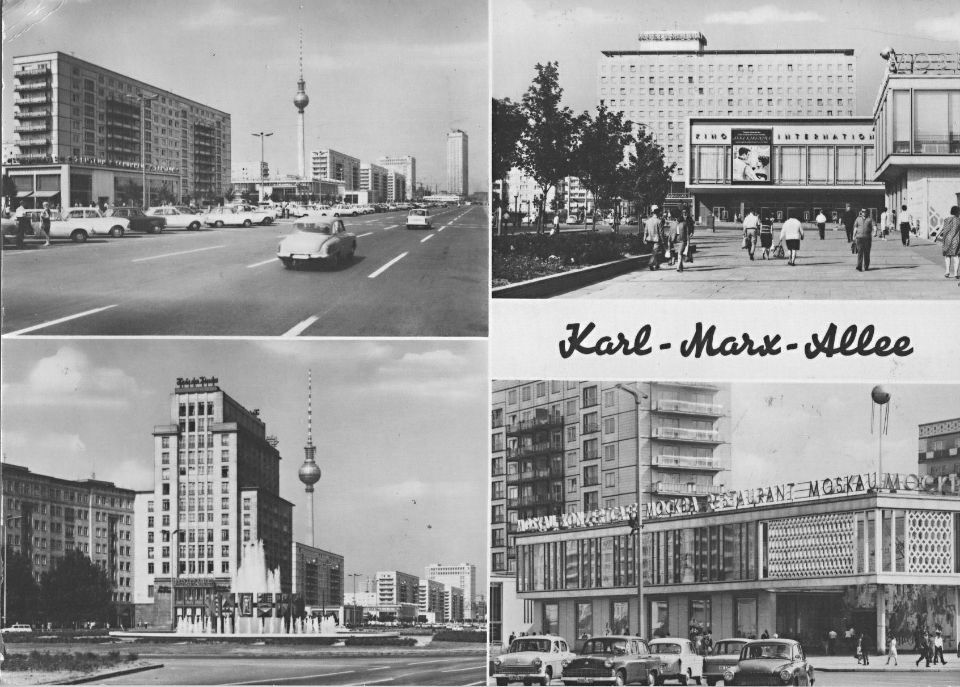

Karl-Marx-Allee, Berlin

The workers constructing this grand boulevard – originally, Stalinallee – downed tools in June 1953, sparking off an uprising that was suppressed with Soviet tanks. The events elicited Bertolt Brecht's poem 'The Solution', where he imagines the East German government 'dissolving the people and electing another'. The eventual boulevard works both as a symbol of the dubious claims to 'socialism' of the regime and of the grandeur of its ideas. An exhilarating, cold rush, lined with tile-clad neoclassical workers' palaces, and enlivened by later, futurist structures such as the dramatic Kino International and the light, elegant Cafe Moskau.

Line A, Prague Metro

Spacious, generous, palatial and imaginative Metro systems are the one typology that was genuinely done much, much better in the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact countries. Beginning with the astonishing living Museum of Stalinism that is the Moscow Metro, and progressing through nearly as awe-inspiring systems in St Petersburg, Kiev, Kharkov, Tbilisi, Dnepropetrovsk, Nizhny Novgorod, Bucharest and Warsaw (among many others), the results are a breathtaking vindication of public space. Along Line A of the Prague Metro, opened in 1978 – between Hradčanská and Želivského - you can find a shimmering amalgam of Moscow's neo-Tsarist underground palaces and the aesthetics of the international space station. It can also get you around.

Linnahall, Tallinn

The former V.I Lenin Palace of Culture in the Estonian capital, built in the early 1980s, is not so much a 'building' in the traditional sense as it is a piece of landscape, a concrete and limestone platform growing out from the grassy bastions of the medieval city and jutting out into the Baltic sea. On top of it, Tallinn youth drink cheap booze, hang out and admire the view towards Finland. Inside is a concert hall and an ice rink, and although these are disused, the building is still used as offices, so if you ask nicely you can see the gorgeous, futuristic main auditorium. The architect, Raine Karp, also designed the slightly more traditional but similarly elemental Estonian National Library, also in Tallinn, which has superb medieval-Brutalist interiors.

Shipyards, Gdansk

In one line of post-communist mythology, this is the place where the system was decisively shaken, when a massive strike wave threw up the independent trade union Solidarity, which took power after the first semi-free elections in a Warsaw Pact country in 1989. The site of the shipyard workers' revolt, with its mostly German-built, red brick halls, metal sheds and towering cranes, is threatened with development, and plays host to artistic interventions, such as model of Tatlin's Monument to the Third International. The current state of the place, loomed over by the huge, steel and concrete anchor and cross monument built as a memorial to workers killed in an earlier wildcat strike in 1970, is a good place to discover the fate of the working class in 'workers' states' – half-derelict, mostly privatised, soon to have a supermarket buit on top. At the entrance is the original board with Solidarity's demands; almost none of them have been fulfilled.