- Home |

- Search Results |

- Underground Airlines by Ben H. Winters

“Listen. Just—I am a free man, as you see, sir, legally so,” I said, then charging on before he could interrupt. “Manumitted fourteen years ago, thanks to the good Lord in Heaven and my master’s merciful will and testament. I have my papers, my papers are in order. I got my high-school equivalency and I’m working, sir, a good job, and I’m in no kind of trouble. It’s my wife, sir, my wife. I have searched for years to find her, and I’ve found her. I tracked her down, sir!”

“Yes,” said Father Barton, grimacing, shaking his head. “But—Jim—”

“She is called Gentle, sir. Her name’s Gentle. She is thirty-three years old, thirty-three, thirty-four. I—” I stopped, blinking away tears, gathering my dignity. “I’m afraid have no photograph.”

“Please. Jim. Please.”

He spread his hands. My mouth was dry. I licked my lips. The fan turned overhead, disinterested. One of the cops, the white one, thick-necked and pink skinned, reared back and slapped the table, cracking up at something his black partner had said.

I held myself steady and let my eyes bore into the priest’s. Let him see me clear, hear me properly.

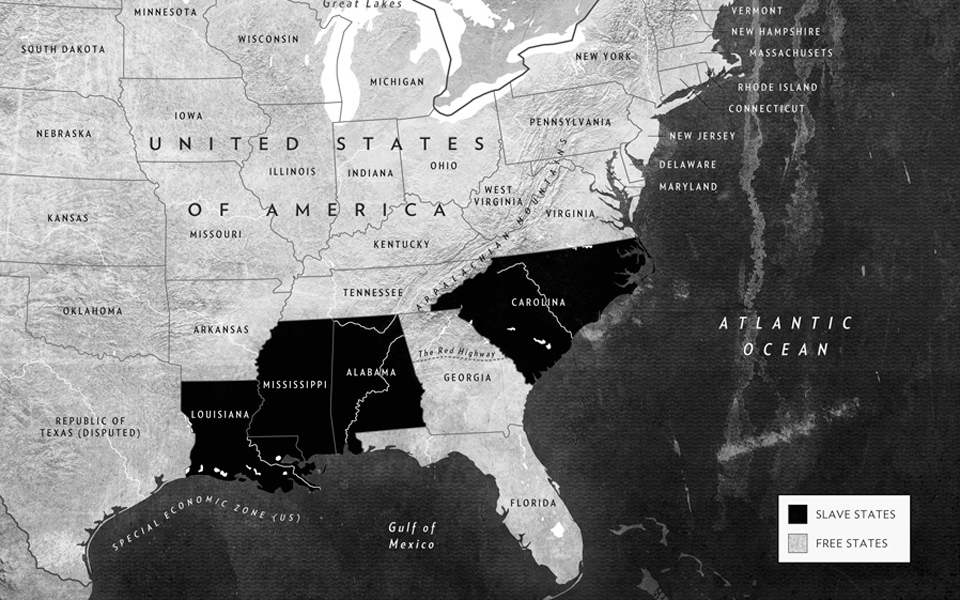

“Gentle is at a strip mine in western Carolina, sir. The conditions are of the utmost privation. Her owner employs overseers, sir, of the cruelest stripe, from one of these services, you know, private contractors. And now this mine, I’ve been looking, Father, and this mine has been sanctioned half a dozen times by the LPB. They’ve been fined, you know, paid millions in these fines, for treatment violations, but you. . . . you know how it is with these fines, it’s a drop in the—you know, it’s a drop in the bucket.”

Barton was shaking his head, gritting his teeth emphatically, but I wouldn’t stop—I couldn’t stop—my words had become a hot rush by then, fervent and angry. “Now, this mine, this is a bauxite mine, and a female PB, one of her age and, and her weight, you see? According to the law, you see—”

“Please, Jim.”

Father Barton tapped his fingertips twice on the table, a small but firm gesture, like he was calling me to order or calling me to heel. The compassionate glow in his voice was beginning to dim.

“You need to listen to me now. We don’t do it. I know what is said of me and of my church. I do. And I believe in the Cause, and the church believes in the Cause, as a matter of policy and faith. I have spoken on it and will continue to speak on it, but speaking is all that I do.” He shook his young head again, looked quickly at me and then away, away from my frustration and my grief. “I feel deeply for your situation, and my prayers are with you and with your wife. But I am not her savior.”

I was silent then. I had more words but I swallowed them. This was a bitter result.

I got through our brief supper as best I could, keeping my eyes on my plate, on my fish sandwich and cole slaw and iced tea. God only knows what I’d been expecting. Surely I had not imagined that this man, this child, would be so moved by the plight of my suffering.

Gentle that he would leap to his feet and charge southward with pistols bared; that he would muster up a posse to kick in the doors of a Carolina bauxite mine; that he would take out his cell phone and summon up the army of abolition.

For one thing, there is no such army. Everybody knows that.

Everybody with sense, anyway. No such thing as the Underground Airlines, not really, not in any grand organized sense. No command center in the deserts of New Mexico, like in that movie they did a few years ago, no paramilitary force with helicopters and !ash bombs, waiting on the orders of a mighty antislavery general to rush into motion.

And now here I was, helpless, watching him eat a hamburger with a paper napkin tucked into his clerical collar, fussily dabbing ketchup from the corners of his mouth

There are rescues, though. There are saviors. It’s piecemeal, it’s small-group action, teams of northerners, daring or crazy, making pinprick raids into the Hard Four, grabbing people up and hustling them to freedom. There are ad-hoc efforts, small organizations, cells, each running their own route of the Airlines. You just gotta know the right people. And this man, this Father Barton here, he was supposed to be the right people. The man to get with. Everything I had heard, all the information I had collected, it all said that here in Indianapolis, in Central Indiana, Father Barton up at St. Cat’s—this was supposed to be the man.

And now here I was, helpless, watching him eat a hamburger with a paper napkin tucked into his clerical collar, fussily dabbing ketchup from the corners of his mouth. Listening to him assuring me in his soft voice, “to allay any concerns,” that everything on the menu had been certified by the North American Human Rights Association, a Montreal-based outfit that inspects supply lines. I nodded blankly. I murmured “oh” into my coffee. “Oh, good.” Like it mattered. Indiana was like most states, a “Clean Hands” state, with a law on the books barring places of public accommodation from serving anything out of the Four. All of the rest of it, all the Canadian supply-chain auditors, all the independent inspectorates and “cruelty-free” certification programs, well, that’s all marketing. Fancy-sounding words to gin up donations for the antislavery non-profits. But Father Barton, he pointed his skinny finger at the little gold seal on my menu like it was some kind of consolation prize.

I can’t get your beloved out of shackles, you poor bastard, but I can assure you that your tomatoes weren’t harvested by a shackled line.

When dinner was done, Barton took out his wallet and I put out my hand and laid it over his.

“Hold on, now.” A little tremor rolled through my voice. “I’m gonna get this.”

“Oh, no.” Father Barton shook his head and didn’t pull away his hand, and we held that pose like an artwork: white hand on a brown wallet, black hand on the white hand. “I can’t let you do that.”

“Come on, now.” I peered at him through my spectacles. “I wanna thank you for taking the time, that’s all. It was good of you to take the time.”

The priest exhaled, nodded slightly, slowly removing his hand from our little pileup. Here’s what he was thinking right then, he was thinking go on and let the man pick up the check—it’s a gift to him, to let him feel he’s done something. I do not want to sound crazy or something, but I do believe that I have this strange power, in certain situations. To read minds, I mean. Not to read thoughts, not exactly, but to read feelings. To read people. To know how people feel.

I dug a few crumpled bills from my coat pocket and smoothed them out on top of the check. Then I pushed a piece of paper across the table, a smudged scrap of napkin. “Here, though. That’s my mobile phone number right there. Just in case you change your mind.”

Father Barton stared at the napkin.

“Please, Father,” I said. “Would you please just take it?”

He took it, and he rose and adjusted his collar, and for a split second, I hated this man, this confident boy. And I believe in the Cause . . . as a matter of policy and faith . . .Go to hell, son, I was thinking, just for a moment, just a bare half of a moment. With your pity for me and your stiff collar and your alabaster cheeks. You go to hell. I didn’t say it, though. Nothing of the sort. I did not raise my voice or bang a closed fist on the table. Anger wouldn’t help.

All it would do maybe was draw the attention of those two cops, the white one with the thick neck and his laughing black partner, maybe cause them to amble over here in that slow cop way, and ask Father Barton if everything was OK. Ask me if I wouldn’t mind providing my paperwork for them to have a peek at, if it wasn’t too much trouble.

I excused myself to use the bathroom, and hurried away, just barely keeping it together.

Once I saw a businessman on TV, the owner of a Midwestern football franchise, and this very wealthy man was proclaiming his personal abolitionist sentiment, while defending his use of the infamous “temporary suspension of status” to add PB muscle to his defensive line. “Do I like the system?” the man had said, shaking his head, in his thousand-dollar suit, his hundred-dollar haircut. “Well, of course I don’t. But I’ll tell you what, this is an opportunity or these boys. And I love ’em. It’s a bad system, but I love my boys.”

I hated that man so much, watching him talk, and I hated Father Barton the same way there in the diner. Slavery was a game to this child, as it was for that slick team owner, as it is for all the football fans who tsk-tsk about the black-hand teams, but watch every Sunday in the privacy of their living rooms. Declaring hatred for slavery was easy for a man like Father Barton, not only easy but useful—gratifying—satisfying. And of course its cold and terrible grip could never fall on him directly.

My anger swelled and then it drained, as anger does. By the time he hugged me consolingly at the door of the diner, by the time the priest was on his way to his car, by the time he stopped to cast a troubled glance back toward me—as I had predicted he would, as I had known he would—that glance found me standing perfectly still in the doorway, a humble man, broken by pain.

I had taken off my glasses and there were tears slipping slowly one at a time down my weathered cheeks. The waitress poked her head out, reminded me that she had the rest of my supper for me, all boxed up, and I could barely hear her, so busy was I composing this face of grief.