- Home |

- Search Results |

- How the rich and powerful are ‘making the world a better place’

In January 2005, on a stage at the World Economic Forum in Davos, one of the original conferences on the MarketWorld circuit, where corporate types paid vast sums of money to mingle with political leaders and others of similar social position, Clinton announced the Clinton Global Initiative. It would, he said, be like Davos, except it would require the rich and powerful people it brought together to commit, as a condition of showing up, to tangible projects for the global good. “I’m a big supporter of Davos, but the world leaders of the rich and the poor countries and everybody in between come to the UN every year in September,” Clinton said, according to Conason, adding, “So what I thought we would do this year is to have a somewhat smaller version of what we do at the World Economic Forum, but that it would be focused very much on specific things all the participants could do.” Decisions and actions, the actual solving of problems, would be the distinguishing feature of CGI. “Everybody who comes needs to know on the front end that you’re going to be asked your opinion about what we should do on AIDS, TB, malaria; what the private sector can do about global warming,” he said. Moreover, “you’re going to be asked to participate in very specific decisions about that and to make very specific commitments.”

The first CGI got many warm reviews. Tina Brown, the veteran magazine editor, wrote, “Clinton seems to have found his role as facilitator-in-chief, urging us to give up our deadly national passivity and start thinking things through for ourselves.” She made a pointed comment about CGI as an alternative to the public, governmental way of solving problems, in light of the colossal state failure exposed by Hurricane Katrina the month before. “Commandeering the role of government through civic action suddenly feels like a very empowering notion—the alternative being to find oneself stranded in a flood waving a shirt from a rooftop,” she wrote.

It would, he said, be like Davos, except it would require the rich and powerful people it brought together to commit to tangible projects for the global good”

Indeed, as CGI developed, it brought together a growing number of people interested in “commandeering the role of government”: investors, entrepreneurs, social innovators, activists, entertainers, philanthropists, nonprofit executives, protocol-equipped consultants, and others, who came to brainstorm new double-bottom-line funds, plot against malaria, and also, since they were in town and so was everyone else, cut their own deals. And with every passing year, their growing presence seemed to shift the center of gravity of UN Week.

Two words came to define CGI: partnerships and commitments. Clinton invited people from various sectors—entrepreneurs, philanthropists, political leaders, labor unions, civil society—to work together on initiatives for societal betterment, and to make public promises about what they planned to achieve.

Early on, Clinton wondered if people would pay money to attend an event whose purpose was to get them to contribute more money, and volunteer on top of that. “I mean, who’s ever heard of paying a membership fee to be asked to spend more money or spend more time?” he joked.

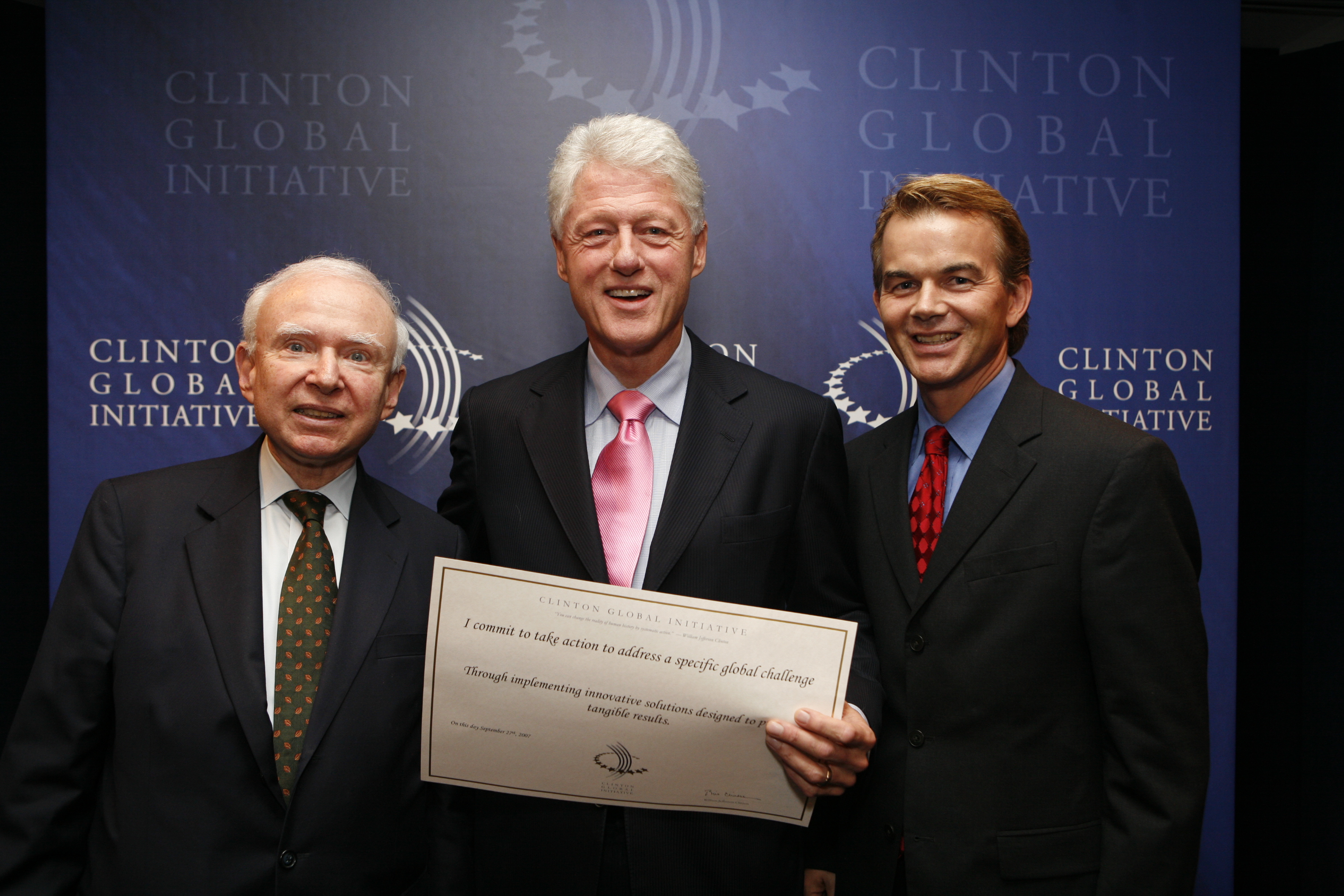

He underestimated himself. The commitments brought rewards. If you worked for a consumer products company and committed to making water filters available to millions, or a foundation that committed to restore some hearing to hundreds of thousands, you might be invited to come up to the CGI stage. There Bill Clinton would stand beside you and read your commitment to the room and praise you. This moment would become, among the doing-well-by-doing-good set, the coveted capstone to a career: People who were influential and/or rich but relatively unknown would bask in the celebrity-like glow. It was also a good way to get your face before a lot of rich and powerful people if, say, you were seeking investors for your new fund. If you owned a plane and had a lot more money where that charitable commitment came from, as the Canadian mining magnate Frank Giustra did, you could soon find yourself trotting the planet with Bill Clinton as your door-opener and bro. You would help him with his foundation, and he might let you into his inner circle, and being in his inner circle might benefit you the next time you bid on a mining project.

By Clinton’s count, the twelve CGI meetings had inspired some 3,600 commitments. The organization claimed that these commitments had improved more than 435 million lives in 180 countries—a figure that was as impressive as it was hard to verify, since this new mode of world-saving was private, voluntary, and accountable to no one. One commitment, titled “Creating Prosperity with Major Corporations,” was put forward by TechnoServe, the antipoverty consulting firm, in partnership with companies such as Wal-Mart, Coca-Cola, Cargill, McDonald’s, and SABMiller; it later submitted a progress report claiming to have implemented a “business plan competition program for entrepreneurs at the ‘bottom of the pyramid.’”

If you owned a plane and had a lot more money where that charitable commitment came from, you could soon find yourself trotting the planet with Bill Clinton as your door-opener and bro”

The new UN Week lived at “this intersection of doing well and doing well by doing good.” Darren Walker credited Clinton, whose event Ford was sponsoring, with the change. “It really was through the vehicle of CGI that so many new actors were mobilized and so many different modalities like impact investing—all of these other things started.” Clinton had used his extraordinary powers of convening to bring improbable partners together, and creative solutions to poverty and suffering had been born. However, Walker said, it was also the case that “philanthropists and commercial enterprises saw in CGI a platform that they could leverage for both doing good and building their brands.” As a result, self-service flirted dangerously with altruism at CGI, in Walker’s view. Why were all these CEOs flying in? “They fly here because they see investment opportunities; they see branding opportunities,” Walker said. Clinton’s brilliance had been in using his gathering “as a way to give people a profile” if they agreed to help people. But this had, by Walker’s lights, clouded the motives of the giving that CGI unleashed. Now others were following its example of barnacling themselves onto UN Week, and “hundreds of side events,” as Walker put it somewhat exaggeratedly, had come into being. “The risk in this is the potential canceling out,” he said. “It’s this idea that you can support a health initiative in Nigeria on the Niger Delta to reduce disease or diarrhea or whatever, and you can also make an investment in a company that is a polluter in the Niger Delta.” These various events—Bill Clinton’s and the raft of other corporate-sponsored world-saving gatherings that benefited from his example—amounted to a kind of parallel UN Week, centered on MarketWorlders.

The privateness of the Clinton Foundation’s endeavors had attracted criticism over the years. Who exactly was giving money? What exactly were their motives? Were they giving at least in part to secure influence or jobs in a future Hillary Clinton administration? Thanks in part to these criticisms—and to the expectation that Hillary would soon win, making the criticisms even more menacing—the conference that had done so much to transform UN Week was meeting for the twelfth and final time. And so there was nostalgia in the air at the Sheraton that week—but also worry. A seething rage was engulfing many societies, fed by the perception that the kind of world-traveling elites meeting at CGI had done a better job of protecting their own interests in recent years than of making the world a better place.