- Home |

- Search Results |

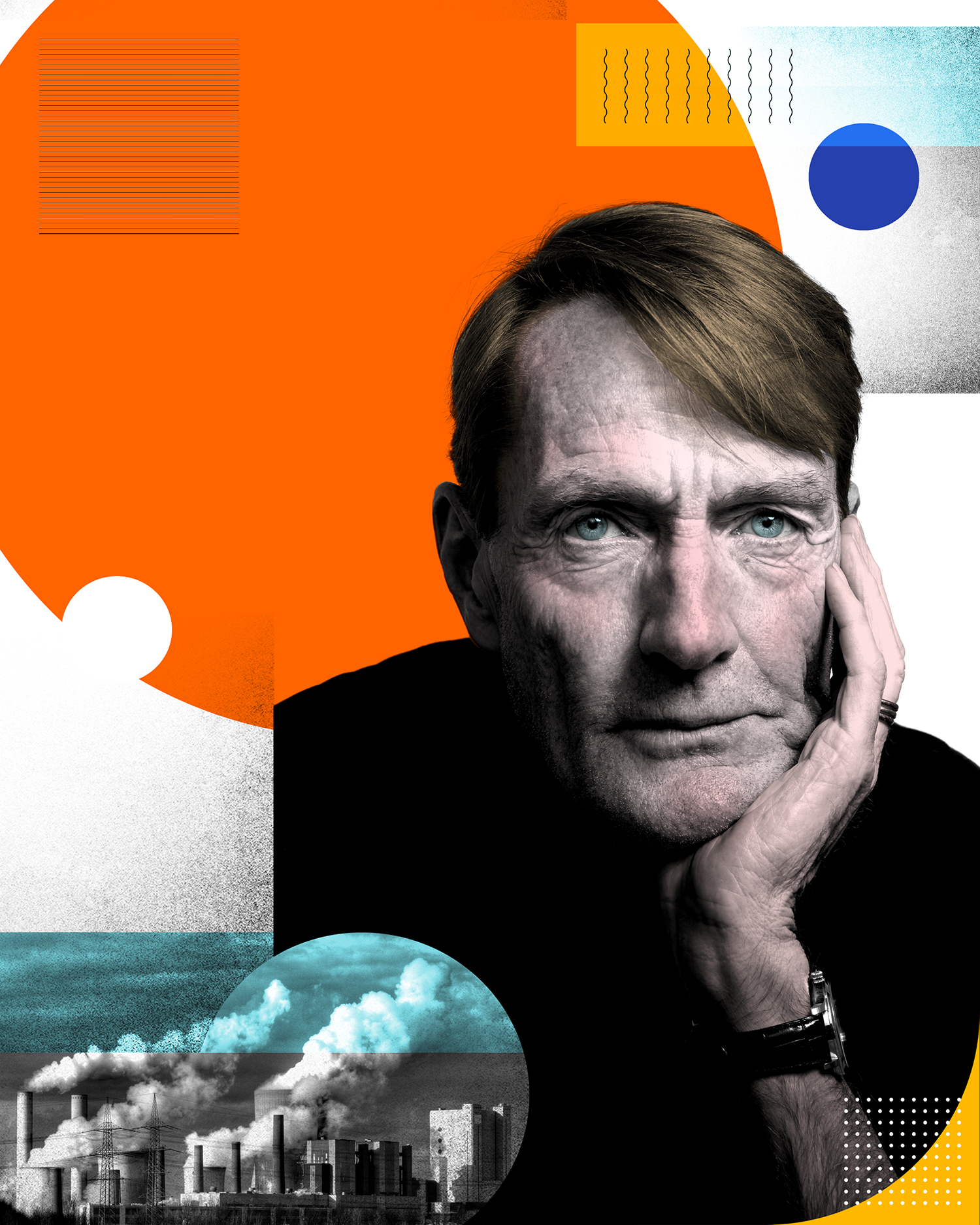

- Lee Child: ‘We will look back and think how lucky we were’

Our daughter was born forty years ago, in Manchester, England. When she was three months old, we flew her to New York to visit with her American grandparents. If we repeated that journey today, our trip would be one metre longer than it was back then. I first went to Australia twenty years ago, to promote my new book. If I went for this year’s book, my trip would be a metre and a half shorter than it was back then. Continents are always drifting, some getting closer, some farther apart.

Naturally we don’t notice. Our brains are tuned to live at human speed, starting with split seconds – the pounce of a predator, Lionel Messi’s swerve in the box – and continuing through minutes and hours – bread rising, meat cooking – and then days and years and lifetimes. I knew my parents and grandparents, and had some idea of their lives and their circumstances, but further back than them I see nothing but vague, gray antecedence. I know I had ancestors, but I know nothing about them, and can’t picture them going about their business. History to me, instinctively, is about a hundred years long. Maybe a hundred and fifty. The future extends maybe another fifty – my baby girl, getting older, going gray, getting aches and pains, getting by on her pension. Call it two hundred years in total, of small human dramas, all played out against a solid and unchanging landscape.

Except the landscape isn’t solid and unchanging at all. When my grandfather was born, New York was three and a quarter metres closer to London than it is today – the width of your kitchen. Sydney was more than nine metres further away – two family cars end to end. If we could find a vantage point, and if we could re-tune our brains and scale them up so we could watch ninety thousand years – or ninety million, or nine hundred million – like we watch ninety minutes of Messi playing for Barcelona, we would see a roaring, grinding, howling, tumultuous planet exploding through one huge change after another, full of constant incident. A blast of heat, a sudden chill, a mountain range thrown up miles in the air, an ocean emptying, a valley flooding, continents floating like blundering rafts on boiling magma, giant beasts flourishing, then disappearing, earthquakes wrenching, volcanoes discharging. It would be like a July Fourth firework show, with rapid stuttering explosions coming thick and fast, too many to count, but each one of them changing everything for ever.

'What happens next depends on how soon the next crisis arrives'

Our re-tuned vision would see faltering prototype populations, of plants and animals and early humans, sometimes flourishing, sometimes struggling, periodically killed off by heat or cold or floods or disasters, one after the other, a rapid-fire parade, rushing on and off the stage. Most of all we would see tsunamis of disease racing back and forth across the globe, constantly, like raking machine-gun fire. Our scaled-up brains would see the Black Death of the fourteenth century, and again in the seventeenth, and the Spanish flu of the twentieth – bang-bang-bang, with barely a pause between.

All of those worst scourges were caused by viruses, tiny insignificant bundles of RNA, never exactly alive, and therefore never exactly dead. Those that did their dirty work a million years ago – or ten million, or a hundred – are still there, most decomposed and useless, but some still preserved, deep in the permafrost, deep in the soil, just waiting. Meanwhile the planet is warming, quite naturally – just a blink of an eye ago, to our re-tuned vision, what we now know as our nations and countries were crushed rock under a trillion tons of ice, until the glaciers receded and survivors emerged and began to build the modern world, which added an unnatural component to the warming, and built a runaway trend. Now the permafrost is softening, and snuffling animals are rooting around, and immense human populations are eating the animals, and now we have our fourth pandemic crisis in seven hundred years.

What happens next depends on how soon the fifth crisis arrives. It seems clear that our current lockdown can’t continue indefinitely. People will be out and about before the Covid virus is gone altogether. It will go endemic, and become a low-level but permanent concern. We’ll get used to it. Maybe a degree of social distancing will endure for a spell, and maybe the Asian habit of wearing masks as a matter of course will become standard practice everywhere. Life will return to some kind of normal. If the next virus waits a few decades, we might respond the same way we did this time. But if it comes sooner, we won’t. We won’t have the will or the patience. Or perhaps the capability – huge populations will be drifting away from the equator, because of climate, displacing failed farmers, who in turn will be moving north and south, toward the poles. And so on. The next virus – and the next, and the next – will have a field day. That’s our future – the same as our past, with tsunamis of disease racing back and forth. We will have no choice but to accept an ancient degree of mortality. In rare moments of repose we will look back and think how lucky people were, to perch briefly on a few thousand years of stability, amid the planet’s four billion years of raging chaos.

Perspectives is a series of essays from Penguin authors offering their response to the Covid-19 crisis. A donation of £10,000 towards booksellers affected by Covid-19 has been made on behalf of the participants. Read more of the essays here.