- Home |

- Search Results |

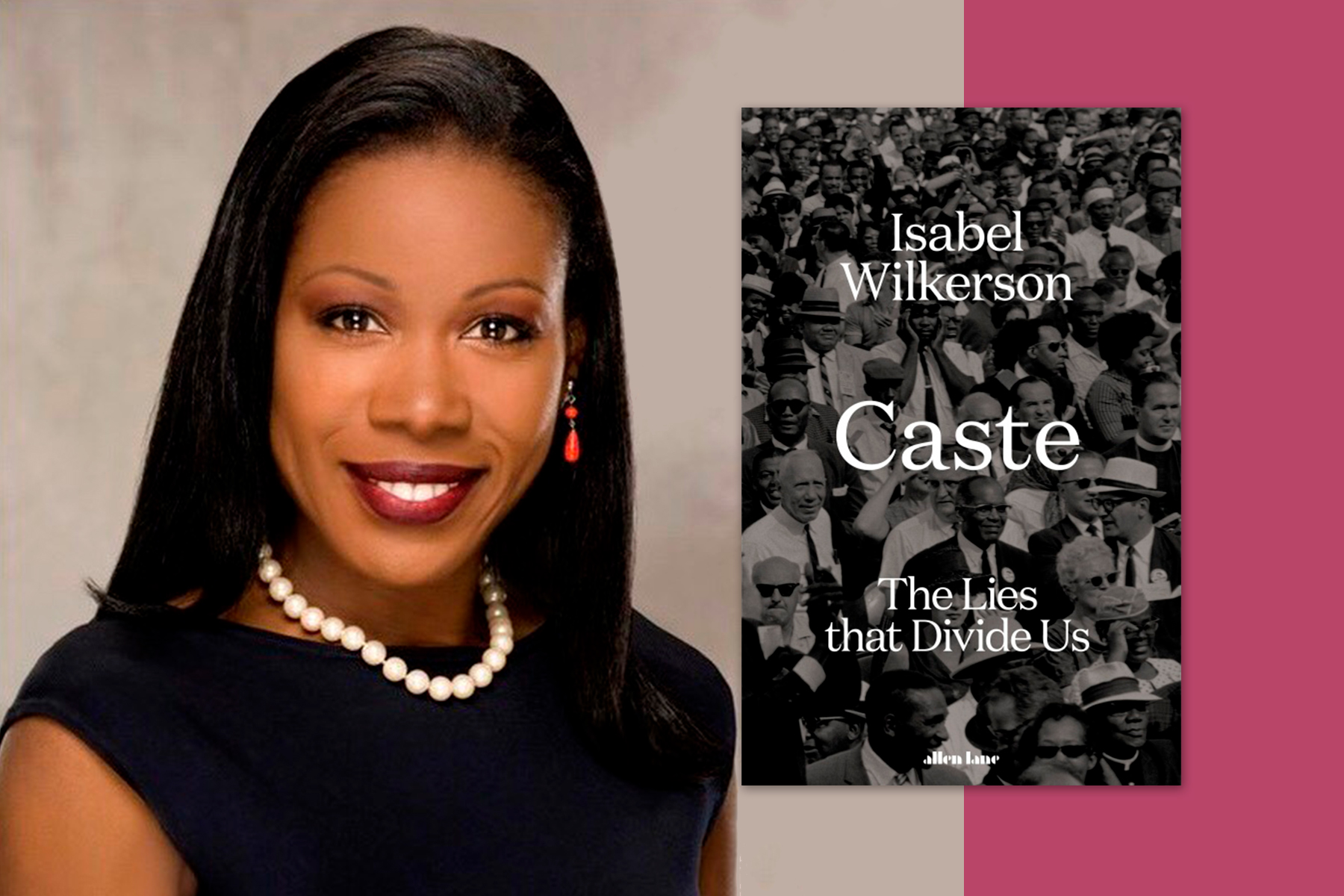

- Isabel Wilkerson on how caste emerged in America

Day after day, the curtain rises on a stage of epic proportions, one that has been running for centuries. The actors wear the costumes of their predecessors and inhabit the roles assigned to them. The people in these roles are not the characters they play, but they have played the roles long enough to incorporate the roles into their very being, to merge the assignment with their inner selves and how they are seen in the world.

The costumes were handed out at birth and can never be re-moved. The costumes cue everyone in the cast to the roles each character is to play and to each character’s place on the stage.

Over the run of the show, the cast has grown accustomed to who plays which part. For generations, everyone has known who is center stage in the lead. Everyone knows who the hero is, who the supporting characters are, who is the sidekick good for laughs, and who is in shadow, the undifferentiated chorus with no lines to speak, no voice to sing, but necessary for the production to work.

The roles become sufficiently embedded into the identity of the players that the leading man or woman would not be expected so much as to know the names or take notice of the people in the back, and there would be no need for them to do so. Stay in the roles long enough, and everyone begins to believe that the roles are preordained, that each cast member is best suited by talent and temperament for their assigned role, and maybe for only that role, that they belong there and were meant to be cast as they are currently seen.

When we are cast into roles, we are not ourselves. We are not supposed to be ourselves

The cast members become associated with their characters, typecast, locked into either inflated or disfavored assumptions. They become their characters. As an actor, you are to move the way you are directed to move, speak the way your character is expected to speak. You are not yourself. You are not to be yourself. Stick to the script and to the part you are cast to play, and you will be rewarded. Veer from the script, and you will face the consequences. Veer from the script, and other cast members will step in to remind you where you went off-script. Do it often enough or at a critical moment and you may be fired, demoted, cast out, your character conveniently killed off in the plot.

The social pyramid known as a caste system is not identical to the cast in a play, though the similarity in the two words hints at a tantalising intersection. When we are cast into roles, we are not ourselves. We are not supposed to be ourselves. We are performing based on our place in the production, not necessarily on who we are inside. We are all players on a stage that was built long before our ancestors arrived in this land. We are the latest cast in a long- running drama that premiered on this soil in the early 17th century.

Americans of today have inherited these distorted rules of engagement whether or not their families had enslaved people

Americans of today have inherited these distorted rules of engagement whether or not their families had enslaved people or had even been in the United States. Slavery built the man-made chasm between Blacks and whites that forces the middle castes of Asians, Latinos, indigenous people, and new immigrants of African descent to navigate within what began as a bipolar hierarchy.

Newcomers learn to vie for the good favour of the dominant caste and to distance themselves from the bottom-dwellers, as if everyone were in the grip of an invisible playwright. They learn to conform to the dictates of the ruling caste if they are to prosper in their new land, a shortcut being to contrast themselves with the degraded lowest caste, to use them as the historic foil against which to rise in a harsh, every-man-for-himself economy.

By the late 1930s, as war and authoritarianism were brewing in Europe, the caste system in America was fully in force and into its third century. Its operating principles were evident all over the country, but caste was enforced without quarter in the authoritarian Jim Crow regime of the former Confederacy.

“Caste in the South,” wrote the anthropologists W. Lloyd Warner and Allison Davis, “is a system for arbitrarily defining the status of all Negroes and of all whites with regard to the most fundamental privileges and opportunities of human society.” It would become the social, economic, and psychological template at work in one degree or another for generations.

It was in the making of the New World that humans were set apart on the basis of what they looked like

A few years ago, a Nigerian-born playwright came to a talk that I gave at the British Library in London. She was intrigued by the lecture, the idea that 6 million African- Americans had had to seek political asylum within the borders of their own country during the Great Migration, a history that she had not known of. She talked with me afterward and said something that I have never forgotten, that startled me in its simplicity.

“You know that there are no Black people in Africa,” she said. Most Americans, weaned on the myth of drawable lines between human beings, have to sit with that statement. It sounds nonsensical to our ears. Of course there are Black people in Africa. There is a whole continent of Black people in Africa. How could anyone not see that?

“Africans are not Black,” she said. “They are Igbo and Yoruba, Ewe, Akan, Ndebele. They are not Black. They are just themselves. They are humans on the land. That is how they see themselves, and that is who they are.”

What we take as gospel in American culture is alien to them, she said.

“They don’t become Black until they go to America or come to the U.K.,” she said. “It is then that they become black.”

It was in the making of the New World that Europeans became white, Africans Black, and everyone else yellow, red, or brown. It was in the making of the New World that humans were set apart on the basis of what they looked like, identified solely in contrast to one another, and ranked to form a caste system based on a new concept called race. It was in the process of ranking that we were all cast into assigned roles to meet the needs of the larger production.

None of us are ourselves.