- Home |

- Search Results |

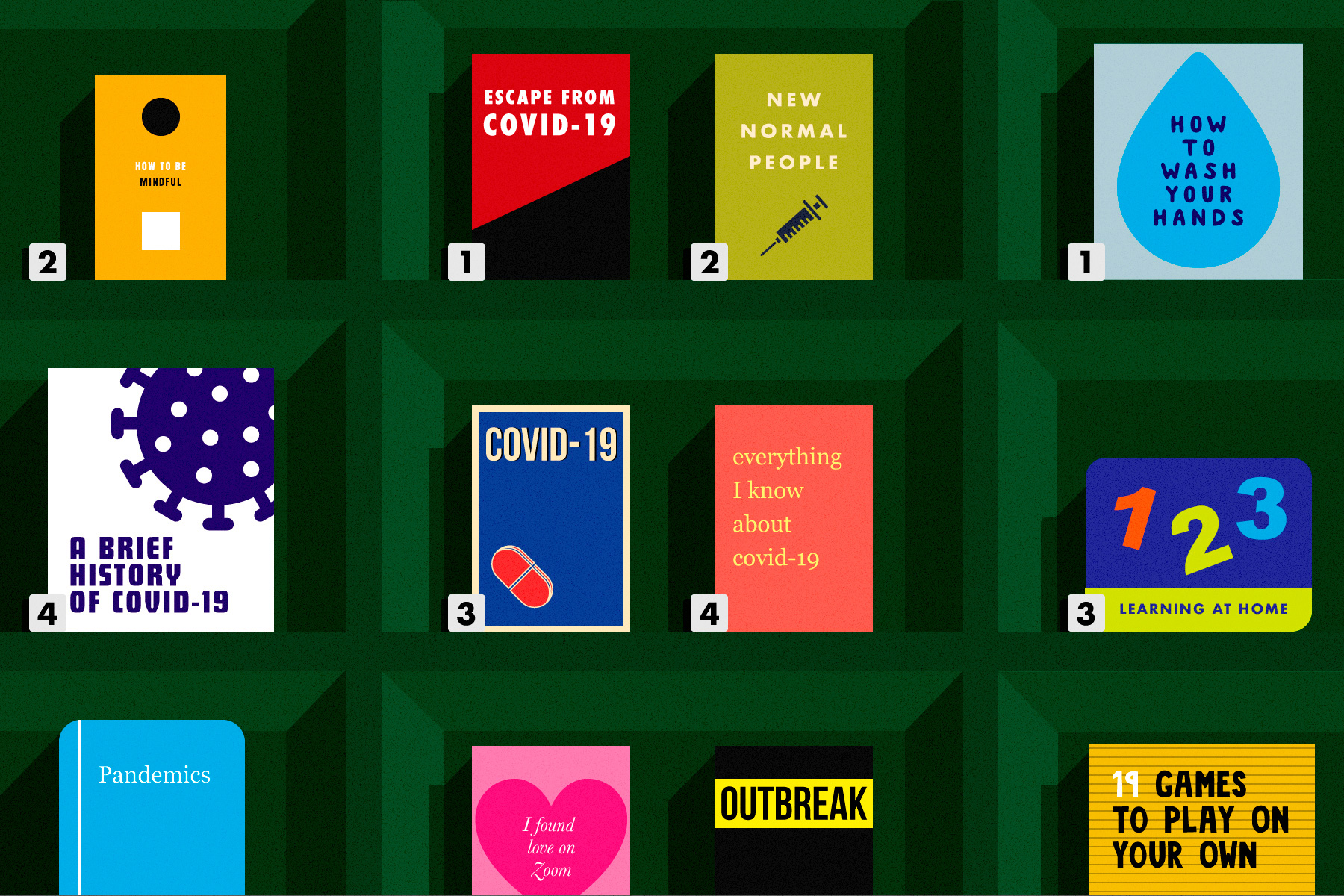

- Will we ever be ready for the Covid-19 novel?

In the early weeks of lockdown, when many people’s days were stripped of commutes and school-runs, lunch breaks and gym sessions, it seemed like a good time to crack on with writing a novel. Or at least, it did until it didn’t: when we realised that most of the world was scrolling, cast adrift in a sea of uncertainty, the news only a rising count of worrying numbers.

Between the middle of March and the middle of April, headlines flip-flopped between whether lockdown was a brilliant time to write a book, or a terrible one. “What happens when every writer on the planet starts taking notes on the same subject?” author Sloane Crosley wondered in the New York Times. “Will we all hand in our book reports simultaneously, a year from now?”

It’s a worthwhile question. Literature reflects our times. The past five years have seen novels emerge out of the EU Referendum vote – Ali Smith’s Seasonal Quartet will conclude in August with Summer, four years after the country chose to leave; a Brexit novel, Middle England, won Jonathan Coe a Costa award – before that, Jonathan Safran Foer was among many authors to tackle 9/11 with Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. Nella Larson and Ishmael Reed responded to the Civil Rights Movement with novels. War, and its long tail, have traditionally proved painful muses.

How, then, will fiction reflect Covid-19 and the seismic hold it has clasped on the world? A century on from that transformative literary movement – Modernism – could we be facing another breaking of form? A determination to “Make It New” once again? Or will readers want to batten down the hatches and find another way to process a grief we never knew to expect?

'All over the country, works-in-progress were being pulled out of drawers and dusted down'

It starts, of course, with the writing. All over the country, as people were furloughed or saw freelance work dry up, works-in-progress were being pulled out of drawers and dusted down, given another edit and sent in on a wing of opportunity.

“There was definitely a big spike in submissions,” says Juliet Mushens, literary agent at Mushens Entertainment. “A lot of agents have said that in the early weeks of lockdown there were a lot of pandemic-based novels submitted. Like, a lot of pandemic-based novels. My instinct was that many of those were not new, but novels people had maybe shopped a year ago, and then thought, ‘hang on, it’s timely now, I’ll give it a polish and send it again’.”

Within weeks, acquisitions were being made. Crime writer Peter May sold a 15-year-old manuscript to publisher Quercus. Entitled Lockdown, it was rushed to release within a month. Six weeks later, author Chloe James secured a deal for Love in Lockdown, a story about “meeting the right person at the wrong time”. It will be released in the autumn.

Writing books is all well and good – impressive, even, given the circumstances. But they need readers. People’s reading habits have been yet another surprising element of lockdown, ranging from those who have battled with a complete inability to concentrate on printed matter, to those tackling some of the canon’s heftiest tomes. In May, a survey by Nielsen Book UK found that 41% of people were reading more since lockdown was imposed, with many turning to crime novels and thrillers for “comfort”.

“Right at the beginning of the lockdown it seemed to be that people were reading a lot of novels from other times; for example, dedicating a lot of time to Middlemarch,” literary agent Emma Paterson says – I concur, knowing at least two people in my immediate circle who tackled the George Eliot epic. “It seemed to me something that lots of people were doing,” she continues. “I sense there was a desire to read outside the current moment.”

While Albert Camus's The Plague – about the reaction of the citizens of a town that has succumbed to a deadly illness – has experienced a remarkable resurgence in popularity, dystopian fiction has been more popular in recent years than it has in 2020. When Donald Trump took office four years ago, bleak classics such as Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Nineteen-Eighty-Four by George Orwell ratcheted up the charts as people anticipated the worst. Yet, now we’re in the midst of a globally compromising pandemic, people don't necessarily want to read about unpleasant possibilities of the near-future. “The appeal of dystopia was the ‘what if’,” Paterson says. “Given that bits of that were actually happening, people no longer wanted to read about it speculatively.”

'Many people might call it a simple book, but so many things are going on in it'

I’ve called Outka up because, in a fit of timing she herself calls “uncanny”, she released a book last year about how the influenza outbreak of 1918 impacted on Modernist literature. Viral Modernism: The Influenza Pandemic and Interwar Literature has proved doubly illuminating given the events that followed its publication, not least because, as Outka outlines, the losses of the influenza pandemic (between 50 and 100 million) were considerably overshadowed by those, albeit numerically smaller ones, of World War One. “People in 1918 felt guilty and disloyal somehow if they got sick with influenza, so they lied about it and how people died,” Outka explained, citing Arthur Conan Doyle as one example who covered up the true cause of his son’s death.

As a result, the pandemic appeared to disappear from the radically different literature that emerged in the 1920s. For nearly a century, academics and readers have cited the devastation of the war and the undoing of Victorian tradition as reasons behind Modernism’s playing with form. But, Outka argues, traces of influenza’s legacy can be found in literature never previously associated with the pandemic.

She traces it in W B Yeats’s poem ‘The Second Coming’ (which he wrote just weeks after his pregnant wife nearly succumbed to the disease) and T.S Eliot’s The Waste Land (both he and his wife caught the flu). Virginia Woolf, who suffered with outbreaks of flu throughout her adolescence, poured her experience of illness into Mrs Dalloway’s titular character, as well as the bells which mark the passing of the day in which the novel was set (in an era when bells would toll to mark death, the influenza outbreak meant the air was near-incessantly filled with them). “These are difficult texts, but this is a moment where you could see that they do match our mood,” Outka has said.

Fast-forward a decade, to the Thirties, and a small flurry of books arrive that are more clearly about the influenza outbreak. Curiously, all are American (Outka points out that the US troops joined World War One far later, and therefore the country was less heavily impacted by it than the UK), and relatively obscure today: Katherine Anne Porter’s Pale Horse, Pale Rider; One of Ours by Willa Cather, They Came Like Swallows by William Keepers Maxwell Jr, and Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel. These texts variously depict the domesticity, the quiet magnitude of personal loss and the uniquely unpleasant symptoms of the 1918 influenza in a way British texts, by this point approaching the Second World War, were unable to.

What can this tell us about the writing Covid-19 might create? Well, for one, that grief takes time to assert itself in literature, especially one disrupted and difficult as that the 2020 pandemic has wrought, in which gatherings and funerals have been outlawed and people must bid goodbye to their loved ones through a screen. But also that people make art to cope with the most extraordinary of circumstances.

“We’re going to have a huge reckoning, and I think that literature can help us do that,” says Outka. “We’re going to need literature to process all this grief that is being felt but not resolved.”

The Covid-19 novels, then, will come. Outka believes there will be a shake-up of form, just as there was a century ago, when War, illness and much-needed changes in society erupted in a tidal wave of brave and brilliant art. As for what they will be, we won’t know for a while. But what we can perhaps guarantee is that they will help us to feel better.