- Home |

- Search Results |

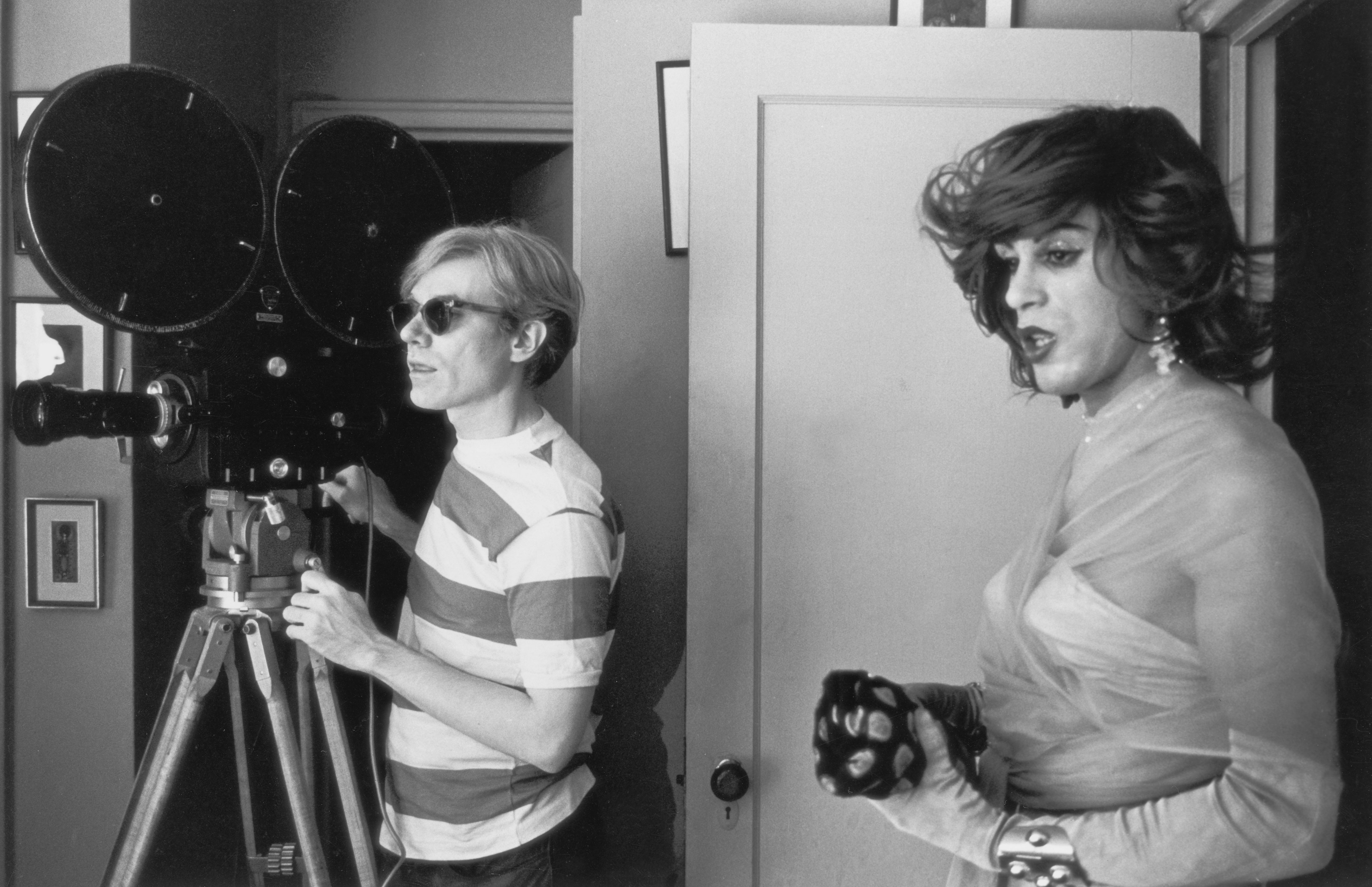

- How Andy Warhol subverted gender to radicalise modern art

How Andy Warhol subverted gender to radicalise modern art

As the Tate unveils a new retrospective of the icon’s work, Blake Gopnik, art critic and author of a new biography on Warhol, looks beyond the celebrated works to a lesser-known side of the pioneering artist.

When Andy Warhol made the 25 paintings of trans women and cross-dressed men that are starring in this spring’s Warhol exhibition at Tate Modern, the project didn’t begin as his idea.

In April of 1974, an Italian dealer offered him a lavish million dollars to create 100 paintings on ‘the subject of a travestite,’ as the dealer requested in badly Englished Italian. But as with so many of Warhol’s greatest works – his Soup Cans, his Flowers, his eight-hour film of the Empire State Building – once he’d recognised that someone else’s idea suited his particular talents, he took that idea further than any other artist might have done. His genius always lay partly in his skills as a sponge, sucking up the culture and ideas around him and putting them to his own special use.

Warhol came more ready to absorb the idea of the ‘drag-queen’ paintings (as they would have been known at the time) than the dealer could ever have imagined – he’d been playing with gender for decades.

Warhol’s gender flexibility went from social liability to commercial selling point.

In as far back as the 40s, a classmate of Warhol’s from art school in Pittsburgh remembered their class painting self-portraits and the now-lost work that Warhol came up with:

He painted his straight, blond hair as a mop of multiple ringlets à la Shirley Temple. When the likenesses were lined up along a wall in the studio, someone in the class inquired: ‘Who the hell is that? Is that your sister?’ ‘No,’ Andy replied matter-of-factly, ‘I always wanted to know what I would look like if I was a girl.’

A second, full-length self-portrait that survives seems to have caused a proper scandal in Warhol’s final year of study in 1949: It showed him full-frontal without a stitch of clothes – except for the pair of feminine Mary Janes on his feet. When Warhol painted that image he was a 20-year-old who was known to wear white nail polish – this, in a city that had just formed a police squad tasked solely with cracking down on anyone who might even appear to be homosexual. Within weeks of the squad’s creation, its cops had shot two gay men.

It wasn’t until Warhol’s graduation and move to New York later that year that his gender flexibility went from social liability to commercial selling point. He’d begun to develop a style full of ‘girlish’ curlicues and dainty hesitations, and in New York, the city’s art directors pounced on it as just what they needed in that post-war moment. After almost half a decade spent working in wartime factories, American women were expected to return to ladylike mores, and Warhol’s illustrations might just help sell them on the idea. In an ad-world still utterly dominated by male illustrators, it was every art director’s dream to find one who could channel the feminine.

As late as 1964, Life magazine could still decry the ‘social disorder’ of homosexuality.

Always acutely attuned to his clients’ needs, Warhol also understood their gender assumptions. ‘Andy had such a good feel for the delicate, the feminine,’ said one (male) art director who hired Warhol to work on a campaign for menstrual pads.

Outside of commissions and commercial work, his best-received personal project of the 1950s consisted of wildly rococo drawings of shoes, each one inscribed to a current celebrity – one of whom was Christine Jorgensen, America’s first transsexual. Warhol’s continued interest in gender extended beyond a simple presentation of feminine roles to women. He displayed curiosity in seeing men take on those roles too, at least in his leisure moments, with Warhol’s friends routinely showing up to parties in drag.

As Warhol began to experiment with Pop Art in the spring of 1961, he mostly left behind the gender play of his 1950s work and persona. It had stopped paying dividends in his commercial illustration (‘manly’ photography had recently stolen its market) and it had never been anything but a liability in finding him acceptance in fine art, or New York social circles.

It was every art director’s dream to find one who could channel the feminine.

As late as 1964, Life magazine could still decry the ‘social disorder’ of homosexuality, and how gay men were more and more set on ‘discarding their furtive ways and openly admitting, even flaunting, their deviation.’ Warhol’s gender-bending was an open admission that didn’t reap benefits.

Men in drag do appear now and then in Warhol’s underground films of the Pop era, and even Warhol’s newly virile shades-and-leather look came ‘topped,’ as it were, with a drag note: Asked why he wore his hair silver, he claimed – lied, actually – that he’d copied the look from the bleached locks of his sidekick Edie Sedgwick. ‘I wanted to look like Edie because I always wanted to be a girl’, he said.

It was only toward the very end of the 1960s that there seemed to be much room, even in vanguard culture, for men who wanted to be, or be seen as women. By the dawn of the 1970s, Warhol had taken up with the transgender pioneer Candy Darling, along with her cross-dressing colleagues Jackie Curtis and Holly Woodlawn, and cast them in movies and as members of his entourage, a move which did him no good in ‘society’ and even got him rejected from buying a country house.

Undeterred, Warhol maintained his allegiance to the gender-bent, for reasons of both aesthetics and justice. If Warhol’s life was truly his most avant-garde creation, as the longstanding cliché would have it, then there was no way that life could conform to standard gender expectations.

Warhol by Blake Gopnik is out now.