- Home |

- Search Results |

- David Attenborough explains what we can learn from the Chernobyl disaster

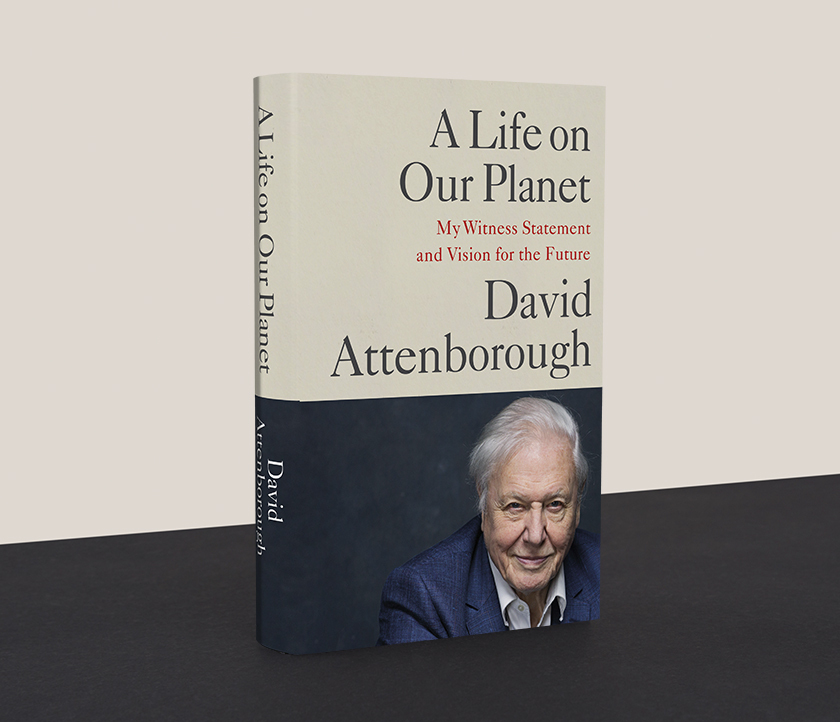

David Attenborough defined his legacy as a natural historian and broadcaster in his book, A Life on Our Planet.

Described as David Attenborough's "masterpiece", A Life On Our Planet explores how we can avoid a future of devastating biodiversity loss, as well as reflect upon a life spent exploring and protecting the natural world. In this extract, Attenborough explains what we can learn about nature's ability to heal from the 1986 Chernobyl disaster.

Surrounding the town’s cultural and commercial centre, are the apartments. There are 160 towers, built at specified angles to a well-considered grid of roads. Each apartment has its own balcony. Each tower its own laundry. The tallest towers reach almost 20 storeys high, and each is crowned with a giant iron hammer and sickle, the emblem of the town’s creators.

Pripyat was built by the Soviet Union, in one busy period of construction in the 1970s. It was the designed, perfect home for almost 50,000 people, a modernist utopia to suit the very best engineers and scientists in the Eastern Bloc, together with their young families. Amateur film footage from the early 1980s shows them, smiling, mingling and pushing prams on the wide boule- vards, taking ballet classes, swimming in the Olympic-size pool and boating on the river.

Yet no one lives in Pripyat today. The walls are crumbling. Its windows are broken. Its lintels are collapsing. I have to watch my step as I explore its dark, empty buildings. Chairs lie on their backs in the hairdressing salons, surrounded by dusty curlers and broken mirrors. Fluorescent tubes hang down from the super- market ceiling. The parquet floor of the town hall is ripped up and scattered down the length of a grand, marble staircase. Exercise books litter the floors of school rooms, neat Cyrillic handwriting scoring their pages in blue ink. I find the pools emptied. The seats of sofas in the apartments have dropped to the floor. The beds are rotten. Almost everything is motionless – paused. If something is stirred by a gust of wind, it startles me.

With each new doorway you enter, the lack of people becomes more and more preoccupying. Their absence is the truth that is most present. I’ve visited other post-human towns – Pompei, Angkor Wat and Machu Picchu – but here, the normality of the place forces your attention on the abnormality of its abandonment. Its structures and accoutrements are so familiar that you know their disuse cannot simply be due to the passing of ages. Pripyat is a place of utter despair because everything here, from the noticeboards that are no longer looked at, to the discarded slide rules in the science classroom, to the shattered piano in the café, is a monument to the capacity of humankind to lose everything it needs, and everything it treasures. We humans, alone on Earth, are powerful enough to create worlds, and then to destroy them.

On 26 April 1986, reactor number 4 of the nearby Vladimir Ilyich Lenin Nuclear Power Plant, known to everyone today as ‘Chernobyl’, exploded. The explosion was the result of bad planning and human error. The design of Chernobyl’s reactors had flaws. The operating staff were not aware of these and, in addition, were careless in their work. Chernobyl exploded because of mistakes – the most human explanation of all.

Four hundred times more radioactive material than that expelled by the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs combined was sent over much of Europe on high winds. It fell from the skies in raindrops and snowflakes, entered the soils and waterways of many nations. Ultimately it broke into the food chain. The number of premature deaths caused by the event is still disputed but estimates range into the hundreds of thousands. Many have called Chernobyl the most costly environmental catastrophe in history.

Sadly, this isn’t true. Something else has been unfolding, everywhere, across the globe, barely noticeable from day to day for much of the last century. This too is happening as the result of bad planning and human error. Not one hapless accident, but a damaging lack of care and understanding that affects everything we do. It didn’t begin with a single explosion. It started silently, before anyone realised it, as a result of causes that are multi- farious, global and complex. Its fallout cannot be detected by a single instrument. It has taken hundreds of studies across the world to confirm that it is even happening. Its effects will be far more profound than the contamination of soils and waterways in a few unfortunate countries – it could ultimately lead to the destabilisa- tion and collapse of everything we rely upon.

This is the true tragedy of our time: the spiralling decline of our planet’s biodiversity. For life to truly thrive on this planet, there must be immense biodiversity. Only when billions of different indi- vidual organisms make the most of every resource and opportunity they encounter, and millions of species lead lives that interlock so that they sustain each other, can the planet run efficiently. The greater the biodiversity, the more secure will be all life on Earth, including ourselves. Yet the way we humans are now living on Earth is sending biodiversity into a decline.

We are all culpable but, it has to be said, through no fault of our own. It is only in the last few decades that we have come to under- stand that every one of us has been born into a human world that was always inherently unsustainable. But now that we do know this, we have a choice to make. We could carry on living our happy lives, raising our families, busying ourselves with the honest pursuits of the modern society that we have built, whilst choosing to disregard the disaster waiting on our doorstep. Or we could change.

This choice is far from straightforward. It is, after all, only human to cling tightly to what we know, and discount or fear what we don’t. Every morning, the first thing the people of Pripyat would have seen on drawing back the curtains in their apartments was the giant nuclear power station that would one day destroy their lives. Most of the inhabitants worked there. The remainder relied on those who did for their livelihoods. Many would have understood the dangers of living so close to it, yet I doubt whether any would have chosen to switch the reactors off. Chernobyl had brought them that precious commodity – a comfortable life.

We are all people of Pripyat now. We live our comfortable lives in the shadow of a disaster of our own making. That disaster is being brought about by the very things that allow us to live our comfortable lives. And it is quite natural to carry on in this way until there is a convincing reason not to do so and a very good plan for an alternative. That is why I have written this book.

The natural world is fading. The evidence is all around. It has happened during my lifetime. I have seen it with my own eyes. It will lead to our destruction.

Yet there is still time to switch off the reactor. There is a good alternative. This book is the story of how we came to make this, our greatest mistake, and how, if we act now, we can yet put it right.