- Home |

- Search Results |

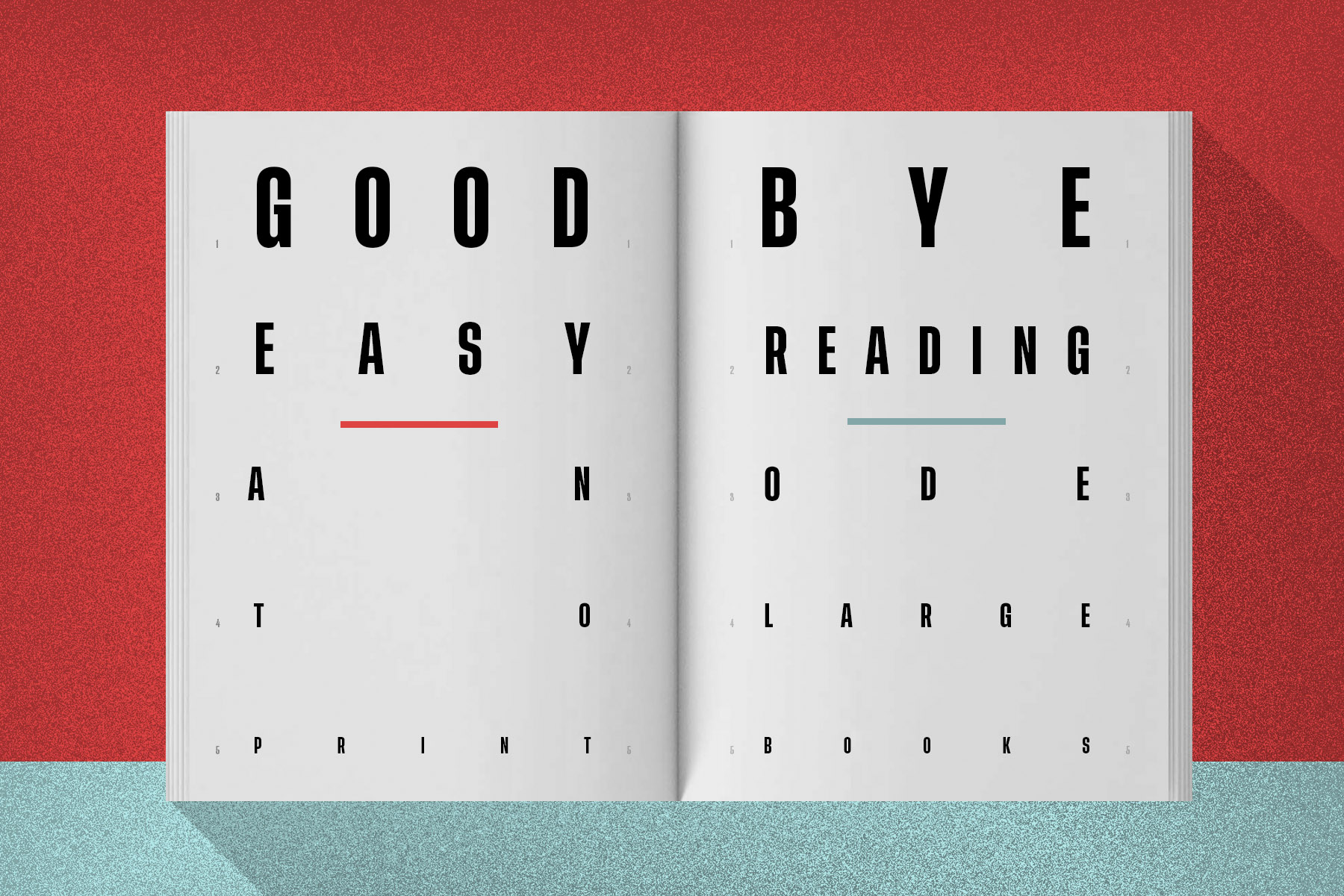

- Saying a sad farewell to large print books

In the cut and thrust world of publishing, it’s reassuring to know that there are still a few things that are impervious to the march of time.

This morning, I typed the phrase ‘large print books’ into Google to see what would emerge. The auto-complete function immediately made a confident plump for what my next typed words would be.

They were, as any visually impaired reader could probably guess by now, ‘Danielle Steele’.

It brought back vivid memories of my early life as a reader with a visual disability. Because, as a teenager with a voracious appetite for prose, there was, I long believed, some kind of establishment plot to force me, upon pain of illiteracy, to never read anything other than Going Home or No Greater Love for as long as I had a library card.

'I suspected that the librarians of Chester in the mid-1990’s hated me'

At first, I despised reading large print books. Not because they were so ludicrously heavy (I actually found carrying four large print novels in my school bag was a more than adequate replacement for a gym membership) but because the scope and range of titles published in this form were never intended for an adolescent who craved to explore the fantastical minds of Burroughs, Camus, Mailer and Trocchi.

I really shouldn’t have been surprised. Because for every one visually impaired teenager with a lust for the drug-addled avant-garde end of literature, there were seventy-dozen pensioners with an equal ardour for the kind of romantic fiction that involved yachts, horses, housewives, errant millionaires and phrases such as "swept off her feet".

I suspected that the librarians of Chester in the mid-1990’s hated me nearly as much as the fiscal bean-counters at the town hall. Whoever it was in council offices who looked after local library budgets must have danced a less-than-dignified jig of joy when I moved to university in the North East at the age of 18.

'I managed to get a large print copy of London Fields by Martin Amis delivered to my local library around the time of my GCSEs.'

Why? Because, stubborn devotee of the written form that I was, I simply pestered, demanded, begged and whimpered until large print versions of the books I wanted were ordered (at considerable expense) to be lent out to absolutely nobody except myself.

There have been many literary moments of euphoria in my life but I can’t think of one that gave me more joy than when (on the recommendation of Damon Albarn in an interview I caught on Channel Four), I managed to get a large print copy of London Fields by Martin Amis delivered to my local library around the time of my GCSEs.

This isn’t the time and place for me to rhapsodise about the blistering, scabrous, grotesque and beautiful prose of what is still my absolute favourite novel of all time. But my vanity very much enjoyed having a huge print version of Amis’ masterpiece.

Suddenly, I found that the best way to carry the large print slab was to have it nonchalantly tucked under my arm and placed indiscreetly on pub and college canteen tables. It was a (notably successful) siren call to the kind of girls who were a bit tired of hanging out with lads whose reading tastes never extended beyond Shoot magazine.

'The lending of large print books by members has slumped from 11,000 in 2017 to under 3,000 in 2020'

This was all a quarter of a century ago however. So it was with no surprise whatsoever that the RNIB Library informed me that the lending of large print books by members has slumped from 11,000 in 2017 to under 3,000 in 2020.

With Kindle, e-books and audiobooks all so easily accessible, coupled with the impressively high level of tech-savvy among aging baby-boomers, the large print novel, like teletext and flocked wallpaper, seems about to disappear down one of those myriad social alleyways for good.

My hunch was confirmed when, while writing this, the RNIB informed me that they are closing their giant print library in two months’ time. RNIB Head of Services David Clarke said:

“We understand the decision will disappoint some customers who still use the service, however borrowing numbers have been steadily falling, and the cost to run the service has continued to rise.”

'It’s an inevitable move, albeit one tinged with sadness for a format of book that has a history dating all the way back to 1910'

With membership of the library down to barely a thousand across the UK, it’s an inevitable move, albeit one tinged with sadness for a format of book that has a history dating all the way back to 1910 when the first large print books were published in the USA.

Yet the RNIB informed me that, even after January, if a visually impaired reader contacts them and wants a novel transcribed into a large print format then they will continue to offer the service on a bespoke basis.

It’s a noble vow, but one that I’m pretty sure I won’t be requesting from them.

Because, like vinyl LPs and Aga stoves, the strange aesthetic beauty (and concomitant nostalgia) for large print books will always be trumped by convenience and storage space.

So, looking around my bookshelves I’m realising that this might be my last chance to offload a few large print remnants. If anyone wants a 24 point type ‘preloved’ copy of Naked Lunch then please do let me know...

Image: Ryan MacEachern/Penguin.

What did you think of this article? Let us know at editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk for a chance to appear in our reader’s letter page.