- Home |

- Search Results |

- Your data’s being sold to undermine society’s well-being; here’s how to get it back

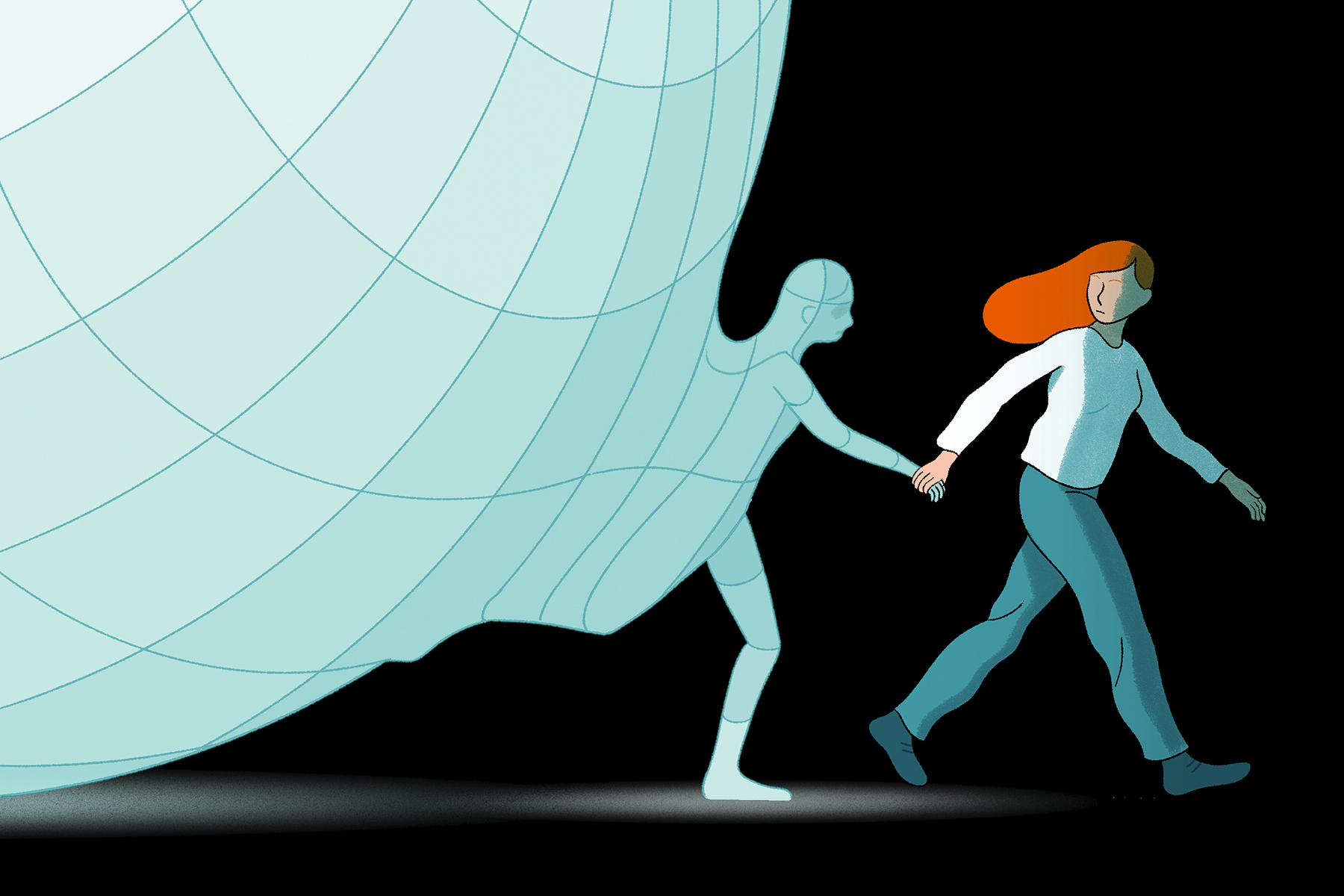

Your data’s being sold to undermine society’s well-being; here’s how to get it back

Every night, your phone sends your personal information to corporations around the world. The impact of the 'data economy' has been catastrophic, both personally and politically. Here the author of Privacy Is Power explains how you can start to take the power back.

You might not know this, but last night, while you were sleeping, the apps on your phone were sending off information about you to dozens of corporations. The information might have included your phone number, email, your exact location, whom you were lying next to, and even whether you had a restful night’s sleep.

Why does this matter? Because most of the problems that tech has brough into our lives –screen addiction, cyberbullying, fake news, and biased algorithms, among others – are the product of an economic system based on mass surveillance.

Much of the internet is funded by the collection, analysis, and trade of personal data: the data economy. Tech companies that earn money primarily through personal data either sell the data to other companies (like data brokers, who compile a file on you and go on to sell it to whoever wants to buy it), or they use the data to sell personalised ads. In other words, either your data is for sale, or your attention is for sale; either way, you are not their customer, and what these companies want is to keep you online as much as possible, so they can collect as much data as possible from you.

Data vultures know all kinds of things about you: who your friends and family are, where you live, whether you are having an affair, your sexual orientation and fantasies, your political tendencies, how fast you drive, your credit history and purchasing power, your illnesses, whether you are thinking of changing jobs, how much you drink, even your weight.

Data vultures often use this data against you. They can show you ads that might lure you into a bad deal, like ads for gambling or expensive payday loans. They might sell your secrets to your insurance company, or your prospective employer, or your government. You might get denied a job, a loan, or an apartment on the basis of data that is sometimes inaccurate – but you will never know about it.

The logic of the data economy is a perverse one: mine as much personal data from people as possible, at any cost. And we are paying too steep a price for digital tech. We are no longer treated as equals; we are each treated according to our data. We don’t see the same content, we don’t pay the same price for the same product, and we are not offered the same opportunities. The data economy is undermining equality.

Tech is making us vulnerable to chronic distraction and cyberbullying of a magnitude never seen before. It is not surprising that there might be a connection between the rise in social media use and the rise in teenage self-harm and suicides. The data economy is hurting our wellbeing, and costing lives.

And tech is hacking our societies, pitting us against each other with inflammatory content, deceiving us with fake news. The data economy is destroying democracy.

Data vultures know all kinds of things about you: your friends and family, whether you are having an affair, your credit history and purchasing power

But tech doesn’t have to trade in our personal data to work well; the data economy is just a business model. Tech can be good.

Good tech is there to help you achieve your own goals, as opposed to tech’s goals. Good tech tells it to you straight: no fine print, no under-the-table snatching of your data, no excuses, and no apologies. ProtonMail, for example, is an email provider that offers encrypted email – no data collection, no tricks.

The surveillance society has transformed citizens into users and data subjects. Those who have violated our right to privacy have abused our trust, and it’s time to pull the plug on their source of power: our data.

Privacy is not a personal preference; it is a political concern and a civil duty. Because of the way our lives are intertwined, we are partly responsible for each other’s privacy. Your data contains data about other people. When you expose your genetic details, you are exposing your siblings, parents, children, and even distant kin. When you expose your location data, you are exposing your co-workers, flatmates, and neighbours.

We need to take personal data off the market. Even in the most capitalist societies, we agree that some things (votes, and the result of sport matches, among others) should not be for sale; personal data shouldn’t be for sale either. The trade in personal data, as well as personalised ads, should be banned. No one should be able to profit from the knowledge that you have a disease, or that you’ve been the victim of a crime. That we allow it to happen is outrageous.

The trade in personal data and personalised ads should be banned.

There is much you can do to take back control of your data. Think twice before sharing; consider how that information could be used against you. Respect others’ privacy; ask for consent before you post pictures on social media. Say ‘no’: don’t consent to the collection of your personal data on websites and apps. Block cookies in your browser. Stop using Google as your main search engine. (DuckDuckGo is a great alternative.) Contact your political representatives and tell them about the privacy policies that you support.

Public pressure will lead to regulation. The Wild West of the internet needs to go through a civilising process similar to the ones that happened to regulate medicinal products, or food, processes that improved society’s health and welfare.

Personal data is like a toxic substance, and it is poisoning individual lives, institutions, and society. Having such little privacy is dangerous. It is time to apply the necessary pressure to end the data economy.

The essay is part of penguin.co.uk's 'Small idea, big impact' series.

What did you think of this article? Let us know at editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk for a chance to appear in our reader’s letter page.

Illustration: Bianca Bagnarelli for Penguin