- Home |

- Search Results |

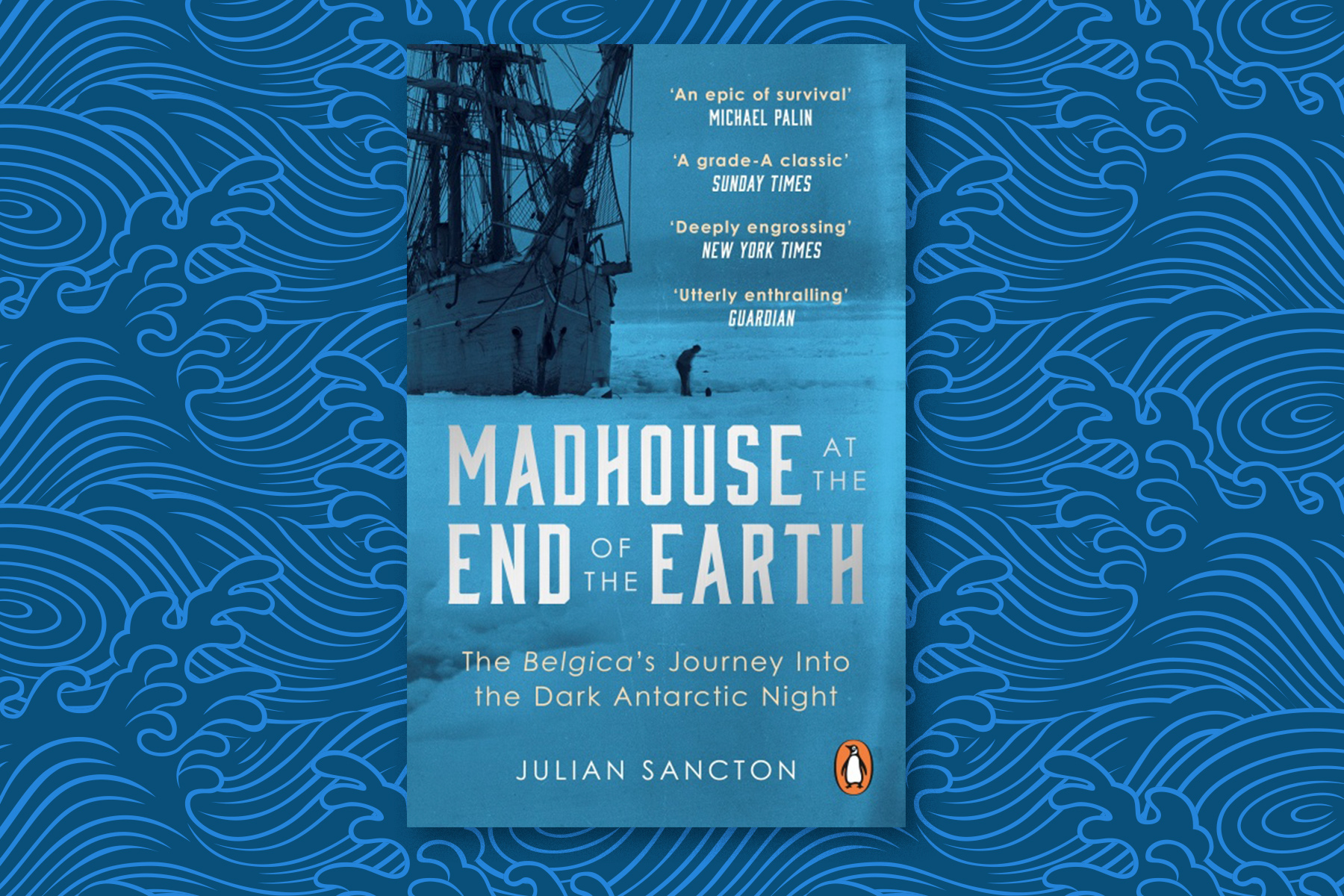

- Eating penguins at the end of the earth

Eating penguins at the end of the earth

A little-known Antarctic expedition in which 'everything that could go wrong, went wrong' has been brought to life in a celebrated new book called Madhouse at the End of the Earth. Here author Julian Sancton shares how he completed his voyage.

In 1897, an expedition led by a young Belgian called Adrien de Gerlache set sail from South America with a simple objective: to reach the end of the earth.

It was a grand era of polar exploration and the crew of the Belgica were determined to make their mark on history. But the harsh Antarctic weather, and a series of costly onboard mistakes, led them to a very different fate: months trapped afloat in the frozen darkness, with nothing to do but descend slowly into madness.

There have been many fine works of narrative nonfiction written about polar adventures, from 1922 classic The Worst Journey in the World by Apsley Cherry-Garrard to The White Darkness, David Grann’s masterful account of British explorer Henry Worsley’s fateful solo trip across The Ice in 2015. But even the most intrepid fans of the genre are unlikely to know the story of the Belgica.

'It sounded like Edgar Allan Poe or Coleridge.'

Journalist Julian Sancton – whose debut book Madhouse at the End of the Earth brings the tale vividly to life, and has earned rave reviews from the New York Times, among others – stumbled over the story when reading a New Yorker article seven years ago.

“It was about NASA's plans for a manned mission to Mars,” he recalls, “and the studies they had done into the effect extended confinement and isolation in extreme circumstances could have on astronauts.

“Part of the background to the story mentioned this polar expedition from 1897 in which everything that could go wrong, did go wrong. To me it sounded like Edgar Allan Poe or [Samuel Taylor] Coleridge. Something clicked.”

Sancton, who has written for the New Yorker himself as well as Esquire and Departures magazine, set to work. His greatest fear – that the reason no one had told the story of the Belgica yet may be that too few details had survived – proved thrillingly incorrect.

“It turned to be one of the best documented expeditions of the heroic age,” he says. “Of the 19 men who left South America aboard the Belgica, 11 wrote some kind of day-to-day firsthand account. It was a historian’s dream.”

The dream had to be turned into cold, hard copy, and so Sancton’s own personal voyage began: several years of research, the highlight of which was a trip to Belgium in 2018.

“I met with a great grandson of Adrien de Gerlache, who very generously opened up his family archives to me. He lived in a house that reminded me of Captain Haddock’s chateau; model ships everywhere, an Arctic sled that belonged to [American explorer] Frederick Cook under the stairs.

'The almost terse poetry of these log entries recorded everything.'

“He pulled out these two giant logbooks from a trunk, and we flipped through the pages together. They were full of this beautiful handwriting his great grandfather had used to record the day-to-day activities of the Belgica. The almost terse poetry of these log entries recorded everything, from seemingly boring details like temperature and the consistency of the ice to encounters with animals. It made the story come alive for me."

The diaries of the men aboard provided Sancton with the meat of his story, but there was still the almost inconceivable scenery of the Arctic to try and conjure into words.

“I wanted to know how this environment looks and sounds and smells,” he says, “and there was just no way to do that without checking it out for myself. So I went to the Antarctic Peninsula and, luckily enough, the weather permitted us to get to the exact same sublime, 100-mile channel that that is actually named after Adrien de Gerlache now.”

No writer can know at the beginning what sort of world their book will eventually emerge into. But there is a particular poignance, after a year in which we have all faced our own versions of an isolation nightmare, to Sancton’s meticulous and sympathetic retelling of the ill-fated Belgica crew.

“Obviously, for those of us who didn't lose a loved one [in the pandemic], it was not as extreme as what the men on board experienced. We were watching Netflix and perfecting our sourdough recipes while they were battling scurvy and eating penguin," he says.

"But the book does explore the deadening, soul-crushing effects that confinement and fear can have. Seeing the same faces at the breakfast table, even if you love them, for 70 days in which the sun doesn’t rise definitely has psychological consequences.”

Not, Sancton insists, that the journey was all bad.

“For the first part of their trip, they had three blissful weeks sailing through somewhere like no other place on Earth,” he says. “Maybe that part will inspire a little wanderlust.”

What did you think of this article? Email editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk and let us know.

Image credit: Ryan MacEachern/Penguin