- Home |

- Search Results |

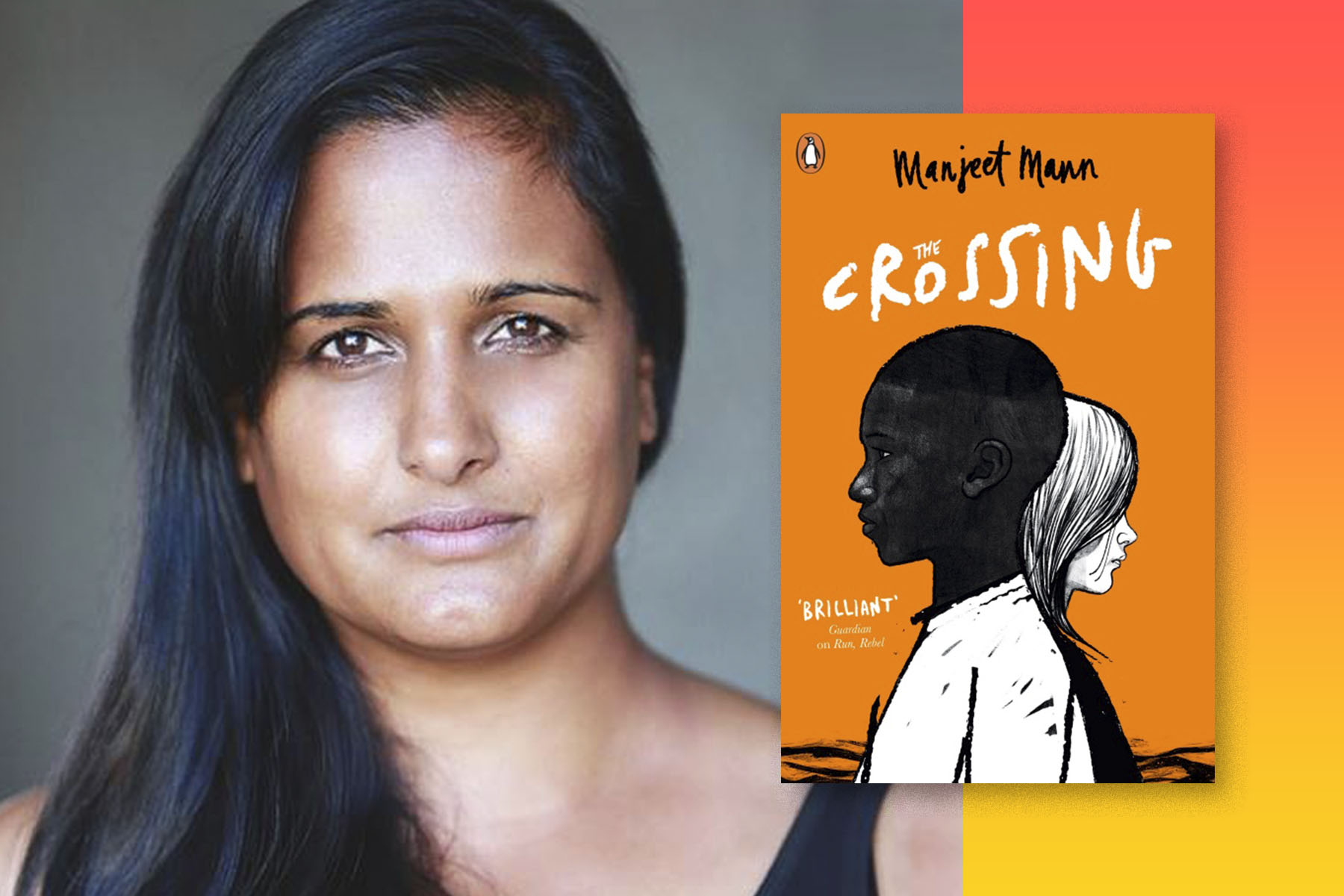

- Lightbulb moments: Manjeet Mann on writing The Crossing

Lightbulb moments: Manjeet Mann on writing The Crossing

The author of The Crossing, a novel about two young people on opposite ends of the refugee crisis, on how channel-swimmers from England and Eritrea inspired her book and how writing can be an act of empathy.

Sometimes, the act of writing a novel is inspired; for Manjeet Mann’s second novel, The Crossing, it feels closer to say she was compelled.

Surrounded by world events beyond her control – specifically the refugee crisis, particularly as it unfolded near her new home in Folkestone and nearby Dover – the actress, playwright, screenwriter and director felt an urgent desire to say something: “I wanted to make sense of what I was seeing, and I wanted to do something that would help build empathy and understanding.”

So, Manjeet began writing The Crossing, the follow-up to her Carnegie Medal-shortlisted Run, Rebel. Aimed at young people and adults alike, the novel tells the stories of Natalie, a teenager from Dover, and Sammy, a teenage refugee from Eritrea – and, eventually, the ways their worlds collide. Their fateful meeting uncovers and explores themes of grief and hope, and asks questions of what such a meeting might mean to the world beyond them. Written in verse, it’s a creative and captivating story that brings crucial empathy to the global refugee story.

To mark the novel’s release, we asked Manjeet about the book’s beginnings, its characters, and why telling the story from a teenage perspective felt so critical.

The idea for The Crossing was motivated by the refugee crisis. What made you want to tell a story about that?

I feel the seeds of the idea were sown in 2015 when I moved to the seaside town of Folkestone, a small town with growing tensions around refugees, unemployment and DFL’s (Down From London people) causing gentrification. The unease was tangible, and easily taken advantage of by right-wing political parties. This reached a crisis point in 2018, when the number of refugees seeking safety coincided with a spate of far-right protests around the UK. Boats arriving on the shores of Folkestone and Dover were a daily occurrence, and the protests in Dover turned violent and brought the town to a standstill.

I have also worked with refugee groups running drama projects for about five years, and was running two such community groups around this time. The focus was on storytelling, and I would try to purposefully steer clear of talking about upsetting things, but I soon found out that the group wanted to share their stories. After the protests in Dover and Birmingham, the sombre atmosphere within the groups was palpable.

Folkestone also has, understandably, a huge channel-swimming community, and in 2018 a small festival in the town was showing a series of channel-swimming films. This juxtaposed with stories of desperate people arriving in boats after crossing the same stretch of water, and police reports into the far-right protest had my head swimming. I wanted to make sense of what I was seeing, and I wanted to do something that would help build empathy and understanding.

Why did it feel important to tell this story from the perspective of young adults?

Because I wanted to appeal to a YA audience. I believe teenage years are when a person is at their sensitive best, willing and ready to learn about new people, places and things. Witnessing the negativity around all the social issues that are presented in The Crossing, there was no question that the book had to be told from the perspective of two teenagers. As I said earlier, I wanted to help build empathy and understanding around subjects where that is perhaps lacking, and appealing to a YA audience, I felt, would be a good place to start.

At what point did you choose to write in verse rather than prose, and why?

I’m not sure it was a conscious choice to be honest. When I sat down to write my first verse novel, Run, Rebel, it just came out that way. I’m a real fan of verse novels, so I’m sure that had something to do with it – and I’d also just finished touring a spoken word, one-woman show around the UK, so I guess at the time performing and writing in verse was on my mind.

I found writing in verse quite liberating; It was easier to deal with big emotional subjects by getting straight to the heart of the issue and saying more with very little. I also like playing with structure, and I like how verse novels can bring words to life on a page with the use of white space and by playing with key phrases. It forces you to want to speak the words out loud, which I think appeals to the actress in me.

Are your protagonists mostly imagined, or a composite of real-life people?

I researched The Crossing for about four years before I put pen to paper. I interviewed people who had fled Eritrea, and I spoke to teenagers in my town about their thoughts and feelings around what was happening in the town: the protests, gentrification etc. It was an eye-opening time. The narrative threads in The Crossing are based on stories I was told, although the characters themselves are not based on any ‘real’ person. I feel Nat, Sammy and Ryan are an amalgamation of all the people I spoke to over that time.

What did you think of this article? Let us know at editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk for a chance to appear in our reader’s letter page.