- Home |

- Search Results |

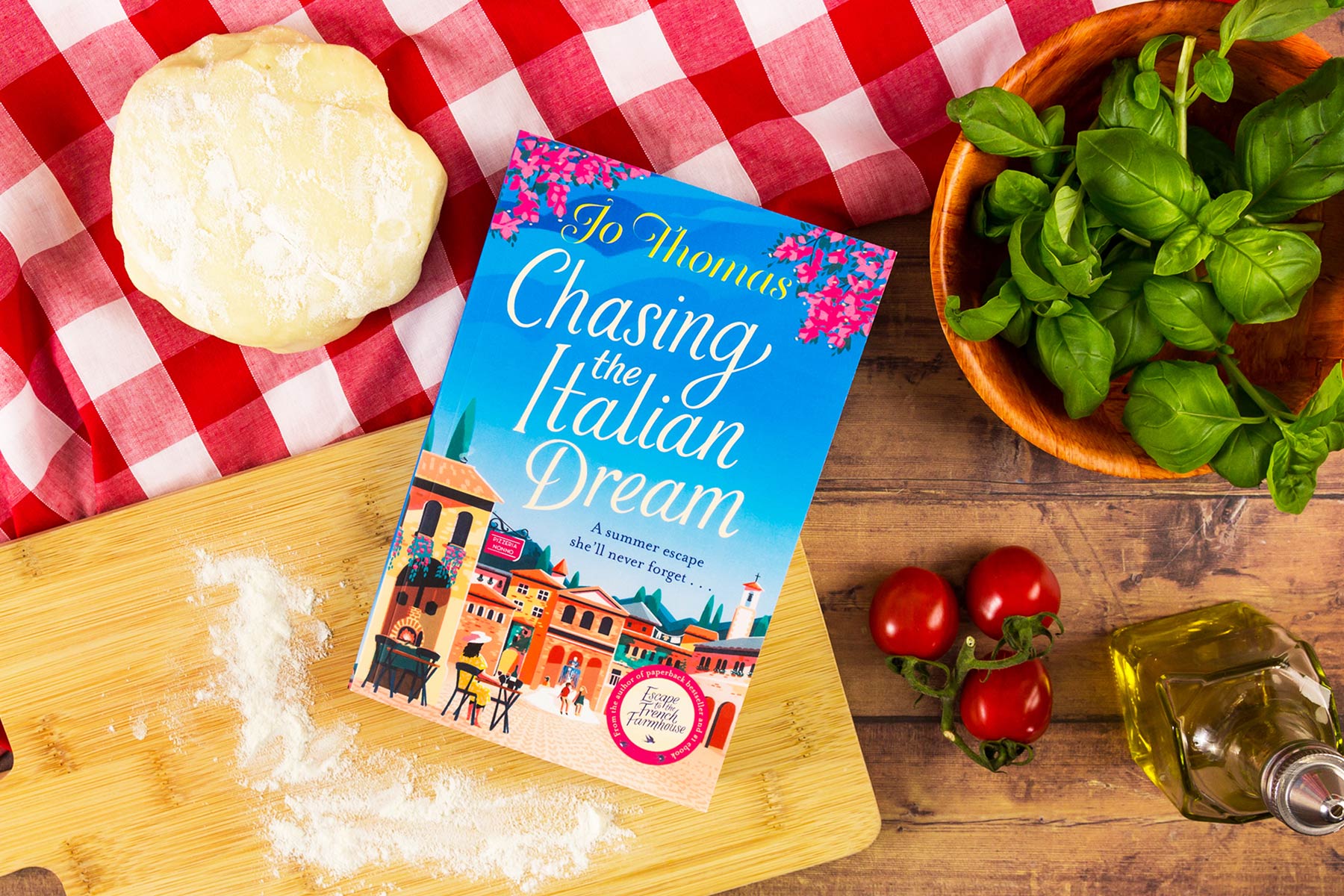

- Chasing the Italian Dream by Jo Thomas

The scent of the tangy tomato sauce hits my nostrils, head and heart before I even taste it. My nostrils tingle, my head practically pops with joy, and my heart is so full it feels like it might explode.

I don’t rush it. I take a moment to savour the joy it brings me. I breathe in deeply, the rich, garlicky sauce, the aroma of peppery olive oil, shut my eyes and let my world recentre itself. I open my eyes and twist tagliatelle, smothered in the familiar sauce, onto my fork. I put it into my mouth, and it’s like coming home to the comfort of the hug that awaits me every year.

‘You look like you never eat!’

‘Oh, Nonna, of course I do. It’s just that nothing tastes like your cooking.’ It’s true. I never have time to cook. I barely notice what I’m eating. It’s all pop in the microwave and ping. Nothing tastes as good as this.

'Nothing feels like having the ones we love here to cook for.'

She puts down the pan she’s drying, comes over and kisses the top of my head. ‘And nothing feels like having the ones we love here to cook for.’ She beams, puts a finger under my chin and lifts it. And although I’m turning thirty-three and it makes me feel like a child again, I love it.

‘You look tired. You’re working too hard,’ she tells me, letting go of my chin.

‘I know, I know. But when I get this promotion it’ll be worth it, Nonna. It’s what I’ve worked for. I’ve dreamt of partnership since I started college. Business law is what I love to do. I want to help people set up their business, live their dreams. Be a part of their goals and the lives they make for themselves.’ Mind you, with the rate at which I’ve been working lately, I wouldn’t say I love it at the moment. But once I get the partnership, I’ll feel all the hard work has been worth- while. Or, at least, that it’s been recognized. I’ve invested as much of myself as my clients have. Given up any social life.

I spin my fork again in the pasta, scoop it up and let the flavours reach into the corners of my mind. It’s as if I’m reacquainting myself with my family home.

I spin my fork again in the pasta, scoop it up and let the flavours reach into the corners of my mind. It’s as if I’m reacquainting myself with my family home. I’m back. I sigh and smile. I’m back.

‘Where’s Nonno? I thought he’d be here, resting. Did the doctor say it was okay for him to be up and about?’

Nonna puts more bread into the basket in front of me and tops up my glass with red wine as I sit at the same kitchen table I’ve sat at every summer since I was a child. No matter how many people are in the house, it accommodates us all. It’s not a fancy kitchen, with the same tiles on the wall that have always been there, the worn work surface, and the huge bottle of olive oil from the few hectares of land where Nonno cares for his olive trees and used to grow vegetables. On Sundays we often went out to the olive grove to picnic, or Nonna would cook on the old forno, the outside oven, among the olive and walnut trees. I loved those Sundays. There’s a big jar of olives on the side too: we ladle them into a bowl at aperitivo time when we sit on the balcony overlooking the street, the café and the apartments opposite. Caged birds get a daily outing on the balconies, and washing hangs like bunting from the sides.

Outside on the street I can hear children playing in the late-evening sunlight, just as we did. Parents are calling them in, but they’re pleading to stay out a little longer. I remember not wanting the day to end until the sun finally went to bed. I know, too, that teenagers will be in the square, hanging around the bocce pitch. And Nonno will tut at the rubbish they leave when he goes there to play. I remember being one of those teenagers and not wanting our evening to end. Especially not when I had a boyfriend. I wanted it to go on and on, and in some ways it did, for years. But that seems a lifetime ago. And the older groups of young people will be gathering in the cafés around the square, drinking coffee and talking until the heat has gone from the day. I remember wanting to be a bilingual businesswoman, spending my time between here and London, the best of both worlds. That was when I thought anything was possible. Before I discovered it wasn’t.

‘He’s at the restaurant,’ Nonna says, putting the big pan away, ready for it to come out in the morning. Everything in its place, as it always has been. The pans hanging by the big oven. The chipped jug beside it with wooden spoons and ladles.

‘At the restaurant? What’s he doing there?’ I stop eating, fork held in mid-air, tagliatelle and sauce dripping from it.

‘He had a few customers tonight. He didn’t want to let them down. Old customers.’ She looks up at the clock on the wall and I can see she’s worrying.

‘Eat, eat,’ she tells me, patting my shoulder.

I put my fork into my mouth, chew and swallow. ‘But surely he shouldn’t be working. He’s only been out of hospital for a week or so.’

'You know what Nonno is like. That restaurant is his lifeblood.'

She shrugs. ‘But 1 He hates to shut it. Besides, he is doing much better. Even playing bocce again!’

‘Bocce!’ I can see him now, with the same group of friends he’s been playing with for as long as I can re- member. Under the big olive tree in the square, with the metal bench under it, in front of the entrance to the narrow cobbled street where the restaurant is. A big round sign, ‘Pizzeria Nonno’, hangs out from the old stone wall over the metal gates leading into the restaurant courtyard. He likes playing bocce in the town square so he can keep an eye on his domain just down the street.

‘Have they agreed which rules to play by yet?’ I ask, still smiling.

‘No,’ says Nonna matter-of-factly. ‘I don’t think they ever will!’

I scoop up another mouthful. ‘I’ll go down to the restaurant and help him finish up,’ I say.

Nonna stops what she’s doing, a little misty-eyed. ‘Nonna, are you okay?’

‘Yes, yes.’ She waves a tea towel and looks at me.

‘You’re a good girl, Lucia.’ She cups my face and kisses me, like only a grandmother can, with pure love, leaving her lips on my forehead long enough for me to know how she feels. Those kisses say everything.

I take a big sip of wine.

‘Don’t rush. Finish your food,’ she instructs. ‘There’s more if you want it.’ She points to the pot on the big old cooker. Then she sighs. ‘The stove is getting old, like me and Nonno.’

‘You’re not old, Nonna.’ I laugh but there’s a hint of sadness in her eyes. ‘You never change. Never any older.’ And it’s true. I don’t remember her ever looking any different. Nothing here changes, and that’s why I love it. Just the way it is.

She laughs, her chest wobbling with her chins. ‘But it would be nice if I had a cooker that worked better!’

I’m so full I can barely move, and happy, really happy. I can feel my shoulders dropping and the tension easing in my neck.

I finish my pasta, wipe out the inside of the bowl, noting its familiar worn pattern, with a piece of ciabatta and pop it into my mouth. I’m so full I can barely move, and happy, really happy. I can feel my shoulders dropping and the tension easing in my neck.

‘I’ll go and meet Nonno,’ I say, standing and picking up my bowl.

Nonna takes it from me. ‘He’ll love that,’ she says, turning back to the sink, where I think she has probably stood all her married life. ‘Just be careful walking through the square. Those youngsters can be boisterous. And walk back with Nonno.’

‘I’ll be fine, Nonna,’ I say, kissing her again and grabbing my bag.

I leave the apartment and cross the piazza, the town square, and walk towards the cobbled street leading off it. The piazza has stone arches all the way around it, under which people sit and eat in the more expensive tourist restaurants. Not that Castel Madrisante is teeming with tourists, but those who arrive in Naples and are looking for some countryside often head out here in search of a rural idyll. Well, it may have been rural once, but it’s not now. More and more people moved out of Naples for the countryside and it’s grown into a busy little town, with apartments built up around the main piazza. The ones above the arched terraces go for huge amounts of money these days, mostly to city people wanting a weekend retreat.

‘Nonno!’ I call, as I open the gates to the courtyard at the front of the restaurant. It’s a sight I will never tire of, with the lemon trees in the pergola and fairy lights. I see him on the covered terrace to the side of the court- yard. A terracotta roof, on whitewashed pillars, stands over a worn terracotta-tiled floor, leading into the restaurant and the kitchen beyond. He’s holding two empty plates and talking to a couple of customers. Candles are flickering on the tables, giving the terrace an orange glow. The air smells of citrus from the lemon trees, with a hint of woodsmoke. Nonno looks up, his face suddenly full of delight. It’s just him working and the one table of customers. Very quiet.

‘Lucia!’ he calls. ‘You remember my granddaughter!’ he says excitedly, to the couple at the table, holding out a welcoming arm to me.

‘Sì, your Welsh granddaughter! Of course!’ They turn to smile at me.

‘Ciao, Lucia! We haven’t seen you for a long time. You’ve grown!’

I wonder how to take that. I’m a thirty-three-year- old woman. Do they mean I’ve put on weight?

‘Ciao, ciao.’ I smile at them both. It feels good to be speaking the language again.

I fall into his arms, squeezing my eyes tight shut, breathing in the smell of woodsmoke from his chef’s whites.

‘Come here, let me see you! Come and hug Nonno!’ He turns and puts down the plates on an empty table as I run over the courtyard to the terrace, as if I’m twelve years old again. I fall into his arms, squeezing my eyes tight shut, breathing in the smell of woodsmoke from his chef’s whites.

Eventually I pull away.

‘You look tired,’ we say at the same time, taking in each other, and laugh.

‘I’m fine,’ we say, and the customers laugh with us. ‘Here, I’ve come to help. You sit down. I’ll finish up.’ He starts to protest.

‘Join us, Enzo,’ say the customers, offering him a glass of wine.

‘Well . . .’ Nonno looks at me, and I know he’s tempted.

‘Va bene Nonno! It’s fine. I know where everything goes, unless you’ve had a sudden change around while I’ve been away.’

He chortles. ‘Well, it’s been a long time. Too long!’ he scolds, wagging a finger. ‘A whole year.’

‘I know, I know, but I’m here now. Siedeti! Sit down.’ I put my hand on his shoulder and push him gently into a chair.

‘But no changes.’ He smiles up at me, his eyes crinkling in his round face. His grey hair is nearly all white now.

‘Bene! Good, now stay there,’ I tell him.

‘Maybe just for a while, and a little wine,’ he concedes, and picks up the glass.

‘Er, are you allowed? Did the doctor say it was okay?’ I say, concerned.

‘Lucia, this is Italy you are in now, not Wales!’ he reminds me, as his customers pour him a glassful and congratulate him on their fabulous pizza.

On the walls I see photographs of Nonno and his father before him … standing in the courtyard in front of the old forno.

I pick up the plates and walk into the cool whitewashed restaurant, where the tables are set with red and white checked cloths and the lights are low. On the walls I see photographs of Nonno and his father before him, holding the pizza peel, the flat paddle, standing in the courtyard in front of the old forno, long since retired. […]

I wash up the plates and clear up the kitchen, turning off the lights. As I return to the terrace, the customers are wishing Nonno goodnight and thanking him for a wonderful meal as always. Nonno walks them from the terrace, across the courtyard to the gates and sees them out, waves, then pulls the bolt across the gates. […]

‘It’s good to have you here, Lucia.’ He smiles and gazes out over the courtyard. ‘The nights are warm, maybe too warm.’

‘It’s good to be here, Nonno. Semplicemente bellissimo.’

‘It’s always like this at this time of year, Nonno. It’s the same every time I come back.’ And it is. I come for the same two weeks every year, the first fortnight of August.

‘It’s good to be here, Nonno. Semplicemente bell issimo.’ A wave of contentment floods over me.

He smiles.

‘Casa dolce casa. Home sweet home!’

And as we sit in the darkening courtyard, I can make out the outlines of the gates at its far side and the buildings beyond in the narrow street, just as they’ve always been. It is so good to be here.