- Home |

- Search Results |

- Terrifying tales: Jay unearths a family secret at her childhood home…

Terrifying tales: Jay unearths a family secret at her childhood home…

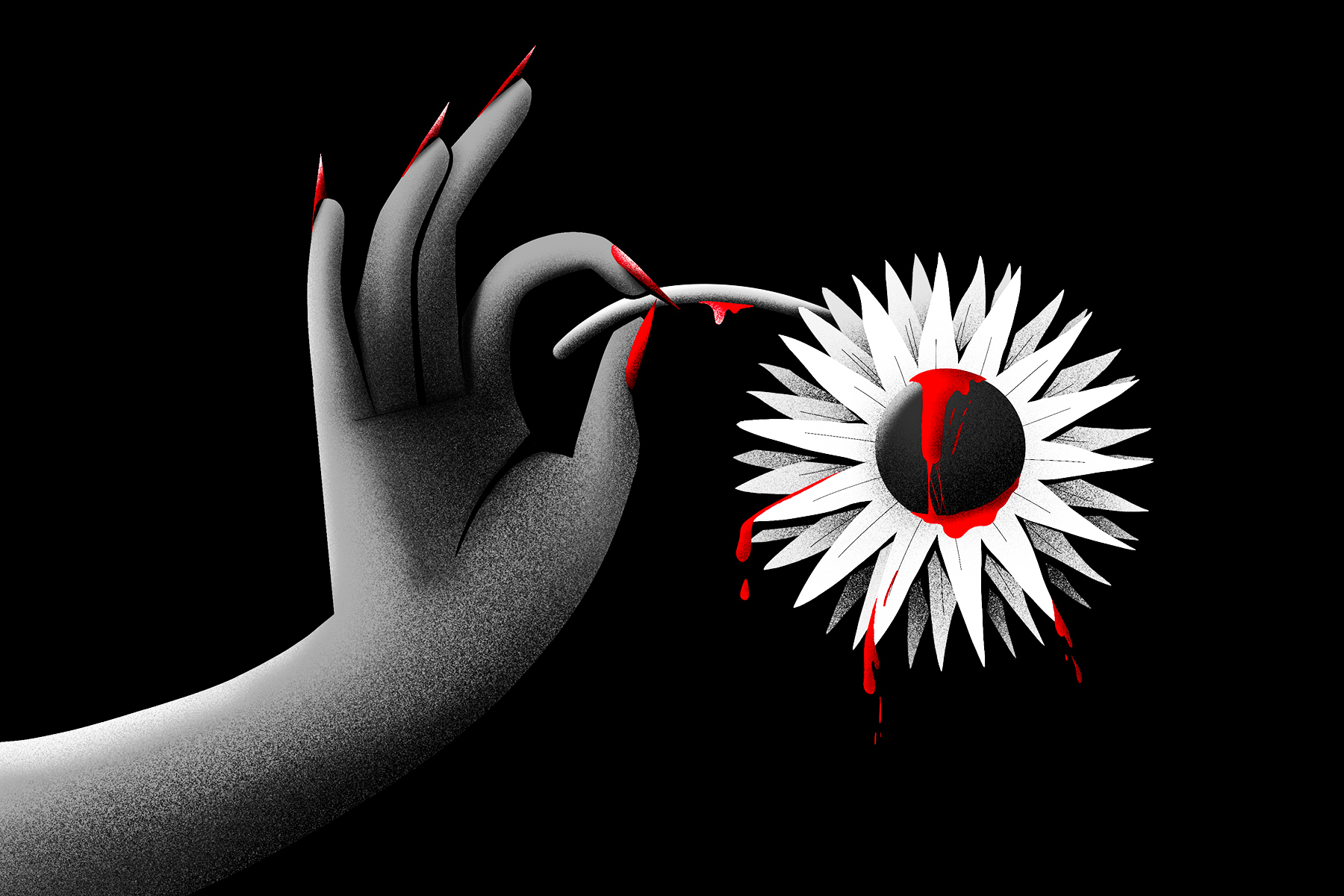

In this short story from her collection Things We Say in the Dark, titled ‘My House is Out Where the Lights End’, author Kirsty Logan ponders: Is there anything scarier than the idea that even those closest to us are unknowable?

Everyone said that sunflowers couldn’t grow this far north and they were right, they couldn’t and wouldn’t, until finally, one day, they did. Pop always said it was because of his Secret Method. He said it in capital letters to make it sound scientific and complicated, but Jay and Yara watched him in secret from Jay’s bedroom window and knew exactly what his method was: he sang to the sunflowers.

She drives up to the old farmhouse with her sunglasses on and the radio off. In her memory it looms so huge, so loud and technicolour, that she’s sure it will overwhelm everything else. But the bright painted boards are faded and rain-dragged, and the tin roof is rusted through in places, and the driveway is overgrown with weeds. She pulls the car to a jolting stop and sits there, watching the empty house as if waiting for someone to come out and get her. No one does.

She climbs out of the car and walks round to the back of the house, where in her memory miles of sunflowers gleam brighter than the sun. She finds a field of withered grey stalks, bent under the weight of their dead heads. The ground is heaving with black seeds, piled thick, gleaming like insect shells. She kicks at them and listens to them sift, an uncomfortably sensual sound. For many seasons the field must have grown wild, alone all summer, then sunk back on itself through autumn, only to repeat the whole thing again next year. A ghost harvest.

Jay goes to the back door of the house. it doesn’t even have a keyhole; it’s just a brass housing and a handle, like on an internal door. Everything is rotted to hell; the wood is soft and yielding under her hand, and the door creaks open easily. The floor is more dirt than lino. The sink, the oven, the cabinets: everything ripped out and taken away.

More Terrifying Tales for Halloween:

- Margaret is overcome by the impulse to kill her husband in this Shirley Jackson classic

- There's a figure out Nate's back window in this Chuck Wendig tale... but is it human?

- On a remote Scottish island, Elspeth is seeing things in this Rebecca Netley novel...

- Between Bram Stoker and certain death, there’s only a door in this Dracula retelling by Stoker's great-grandnephew

The scratch of the straw against her skin as she hoisted the bodies up, the straw hands stroking the nape of her neck, the moans that she knew must be the wind but sounded closer and more alive, the booted legs bumping against her calves and trying to wrap around her ankles, the warmth of them. Pop telling her higher, lift higher, and she strained her arms as much as she could because they were heavy, much heavier than she thought they could be, and finally Pop got them tied to the crossbar and Jay could go inside.

'Jay looks out to the field of rotted sunflowers and straight away she’s thrown back into the past'

At bedtime Jay would wait for Pop to come and tuck her in, which she desired and feared in equal parts, but she shouldn’t have bothered because since he planted the sunflowers he was rarely ever in the house at all. When the moon came up and licked the world silver, Jay opened her window and anchored her feet against the bedstead and rested her belly on the splintery sill and closed her eyes and leaned right out so that she could hear Pop singing to the flowers and imagine that he was singing to her.

One night, driving home with Pop, the rain lashing and his breath steaming the windows and the smell of hops and fart filling the car – Jay didn’t know whether to make a joke about that or just keep quiet – and the country lanes were winding hairpins and the hills left her tummy behind like a roller coaster. The trees seemed closer to the road than usual, like they were raising their arms to scoop her in and whisper secrets. Branches blatted along the roof of the car and wet leaves stroked Jay’s window, and she wanted to roll it down, and she turned her eyes front to ask Pop if she could and a big black shape loomed up fast and smack against the car’s front bumper and thuck over the bonnet and Jay screwed up her eyes so she wouldn’t accidentally see anything in the wing mirror. The next second she snapped her eyes open and turned round in her seat but the road had doglegged and she couldn’t see behind them.

A deer, Pop said, hands tight on the wheel.

But, Jay said.

A fucking deer, Jay, he said, it shouldn’t have been on the road.

And perhaps that should have changed everything; perhaps she should have felt differently about her father then. Scared of him, or suddenly sure that he was a monster; or reassured, even, more trusting that she was a kid and he was a grown-up and he knew what was and was not a deer. But it didn’t change anything. Why would it? They lived in the country, and it’s all nature there. In nature, things die.

'She digs a little way into the dry earth. Her nail catches on something hard and she pulls it out.'

Jay goes back downstairs and through the kitchen and out of the house. She ducks her head and covers the back of her neck with her linked hands to protect it from skittering seeds and she goes into the sunflower field.

There are four crucifixes in the field but she only checks one. She digs a little way into the dry earth, feeling it stick under her nails and settle on her tongue. Her nail catches on something hard and she pulls it out.

A tooth.

It’s big, a molar maybe. No filling.

It could be hers, or Yara’s; sacrificed to the Tooth Fairy and buried out here for some reason. She digs further and finds another hard object; she scoops at it and her palms come up full of teeth, more than ever came out of her and Yara’s mouths combined.

She puts her hand back and her fingers close around a hank of hair and she tugs it from the earth, thinking it still could be hers, it could be Mam’s, remnants from a hairbrush or – the hair comes free and there’s scalp attached, a rough square the size of a tea bag.

Everything is spinning and she hears the dead seeds clacking and the sunflowers creaking and the empty crucifixes leaning down towards her and she digs, she digs, and all the way down it’s teeth and hair and bones and teeth and hair and bones and teeth and hair and...

What did you think of this article? Email editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk and let us know.

Illustration: Alexandra Francis for Penguin