- Home |

- Search Results |

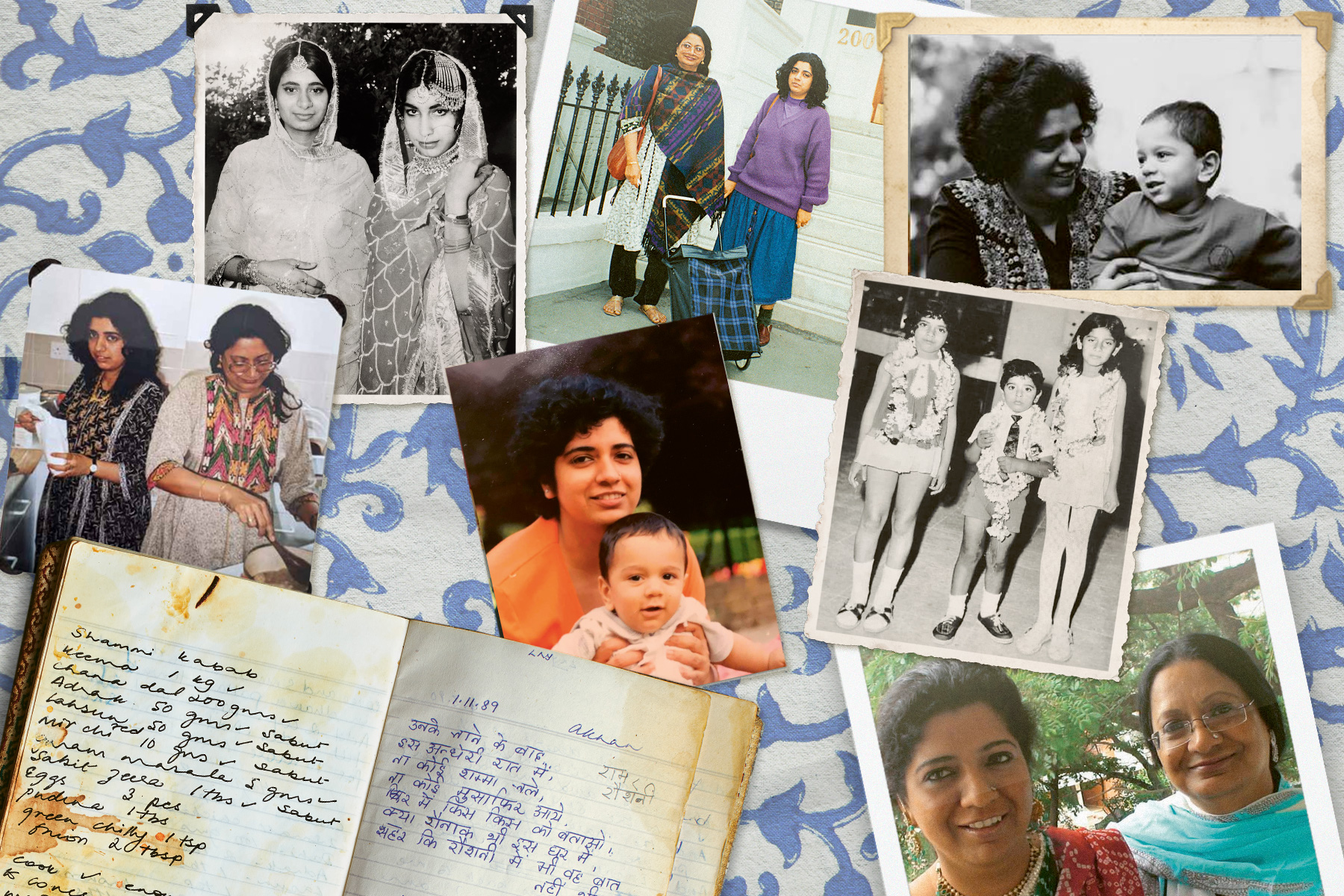

- Asma Khan on food, legacy and the lessons her mother gave her

Asma Khan is sorry that the chai “isn’t ready”. We’re meeting on a wet Wednesday afternoon, a few hours before dinner service in her restaurant, Darjeeling Express. The tea, I’m told, is still brewing. She delivers the unfortunate news in a marigold-yellow Indian suit and a slash of kohl eyeliner that seems to underline her no-nonsense gaze.

Darjeeling Express started as a supper club in Khan’s West London home. Within five years of launching it, she’d opened a small but buzzy restaurant in Soho, staffed with an all-female team of home cooks. The Kolkata-born, London-based Khan was the first British chef to feature on Netflix’s documentary series Chef’s Table, in 2019. Unlike the 35 other chefs that were profiled before her, Khan insisted on bringing the entire Darjeeling Express team into the limelight with her, making sure the producers included each woman’s name and the village she came from. “In my culture, ‘naam’ is ‘name’; it’s also ‘fame’,” she says. “We don’t have either. We are nameless, faceless women who cook every day of our lives,” she explains. Not any more. The restaurant’s popularity skyrocketed; a bigger space was needed.

We are sitting in the dining room of its new location, a gorgeous Grade II listed building in Covent Garden. It had been open for just 10 days when the lockdown hit, in March 2020. Stuck at home, Khan found herself in a reflective mood, time-travelling back to her childhood. The 52 year-old started to write Ammu: Indian Home-Cooking to Nourish Your Soul, a memoir that captures five decades of her life – who she was at each stage, and importantly, what she ate. Its recipes range from the comfort food of her childhood to the dishes that taught her how to cook, celebration feasts, and the sorts of meals she now makes for her sons. She writes as she speaks: with warmth, generosity and a startling directness.

My mother would never ask me ‘How are you?’ or say ‘I love you’. It was, ‘What will you eat?’

“My mother would never ask me ‘How are you?’ or say ‘I love you’. It was, ‘What will you eat?’” says Khan. It seems fitting then, that she has written a tribute to her mother in the form of a cookbook. Its title, Ammu, is a word for ‘mother’ used in South Asian Muslim homes. “It was very important for me to, in her lifetime, write this book,” she says. “I did not want to write it later.”

Khan writes in vivid detail about moving from the bustling Kolkata to damp, dreary Cambridge as a new bride, back in 1991 with her husband Mushtaq, an academic. The experience was something of a culture shock. “In Kolkata, I’d never in my life eaten a single meal alone. I’d never slept in a room alone! There were always so many people around. Everybody ended up staying at our house, because the food was so nice!” she remembers. She had enjoyed a lively childhood, filled with chatter and food made by her mum, the family’s nanny, Ma, and their cook, Islam.

When she moved to the UK, she found herself surrounded by silence. She describes her struggle to navigate her way around an unfamiliar city. “I didn’t know the names of streets! All the houses looked the same to me. Going into a Tube station was traumatic for me, because I didn’t know all the exits. It felt very disorienting,” she says. Khan had been uprooted, and she was lost.

Once every two weeks, she would ring her parents, who remained in India. “I would have this three-minute call where I was speaking to the whole household. Everyone would want to say hello to me,” she says. But for Khan, those brief conversations weren’t meaningful. “There was no way of telling my mother how hard it was. She didn’t give me that space in the conversation to tell her how I was dying, I was so lonely. She didn’t wanna know.” Khan had to figure out how to “break out of the darkness”. And so she learned how to cook. Through mini lamb koftas, machher mamlet (fish omelette), and aloo gobi mattar (potatoes with cauliflower and peas), she found a way home.

From her early supper clubs, to the women without professional training working in her restaurant’s kitchen today, home cooking has been at the heart of Khan’s career. In Ammu, her mother describes the key ingredients of a good meal as the cook’s “generosity and patience”. Anyone who has eaten at Darjeeling Express (or cooked from her 2018 cookbook Asma’s Indian Kitchen) will know this to be true. “I am not impressed by chefs in stainless steel empires,” she says with fiery conviction. The home cook is more impressive, catering for a variety of difficult audiences. “Your family, sullen kids, difficult elders, day in, day out. That patience, that love, that deep sense of duty and service. This is what makes home cooks remarkable, but they are so uncelebrated.” Khan’s ethos is about scooping up and spotlighting those who have not been celebrated. It’s a spiritual practice she inherits from her mum.

Ammu was a businesswoman, too. In a traditional Muslim family like Khan’s, this was not conventional. She describes her mother as a mix of softness and steel. “She was not gonna bend, she was not gonna allow people to knock her over, and she would stand there, protecting others. Possibly, I have that as well.”

Ammu started a catering business in Kolkata in the late 1970s, when Khan was a young girl. In the book, she writes about how Ammu would hire “fallen” women – women who had been abandoned by their husbands, and banished from their family homes. “When my mother would hear of cases where there had been a big blow-out and he had walked off, or left her for some other woman, she would go to the market and stand there and say, ‘She’s gonna work with me from tomorrow. I don’t want anyone to approach her.’” Khan was barely 10, and terrified. Yet what lingered was not her own sense of fear, but the flash of respect she witnessed in the eyes of the other women watching.

“No one dared say anything,” she says. “She was showing them how to live. That you can actually understand your privilege, and make a difference to the lives of others who are not so privileged.”

“Everyone was like, you need to have professionals,” she continues. What she needed was a team of people who could cook with estimates, ratios, and their senses. “It is everything – our sight, aroma, touch, feel, even the sound of the sizzling of the spices. The popping of the mustard seeds. The crackling of the whole cumin seeds. We cook by feelings and emotions.” It wasn’t always easy for Khan to translate those feelings and stories into measurements.

The secret? Her son. He would film her as she cooked, making notes of the exact quantities as Khan continued, as is customary, to measure with her hands and her eyes.

“Mothers are like this!” she says, chuckling. It is a problem she has encountered attempting to get recipes from Ammu, who is due her first visit to Darjeeling Express in May. As per her mother’s instructions, she added “one cup of water”. To her horror, the entire dish burnt. It’s comforting to know that even the professionals are capable of getting it wrong. “She said, ‘You should put one cup’. I said, ‘What cup?’” Ammu pointed to a cup on her windowsill. “The cup on her window was a bloody jug! It’s yellow and this big,” she says, gesturing.

“‘I said, ‘Why did you say cup?!’ She said, ‘Yeah it’s my cup.’”

What did you think of this article? Email editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk and let us know.

Image: Urszula Sołtys