- Home |

- Search Results |

- Take a walk with Rob Cowen on a chilly February evening

Take a walk with Rob Cowen on a chilly February evening

Rob Cowen’s Common Ground was recently featured on BBC's Winterwatch when it was chosen as one of the nation's favourite nature books, just behind Fingers in the Sparkle Jar by Chris Packham and Tarka the Otter by Henry Williamson. Walk alongside Rob on a chilly February evening in this stunning excerpt.

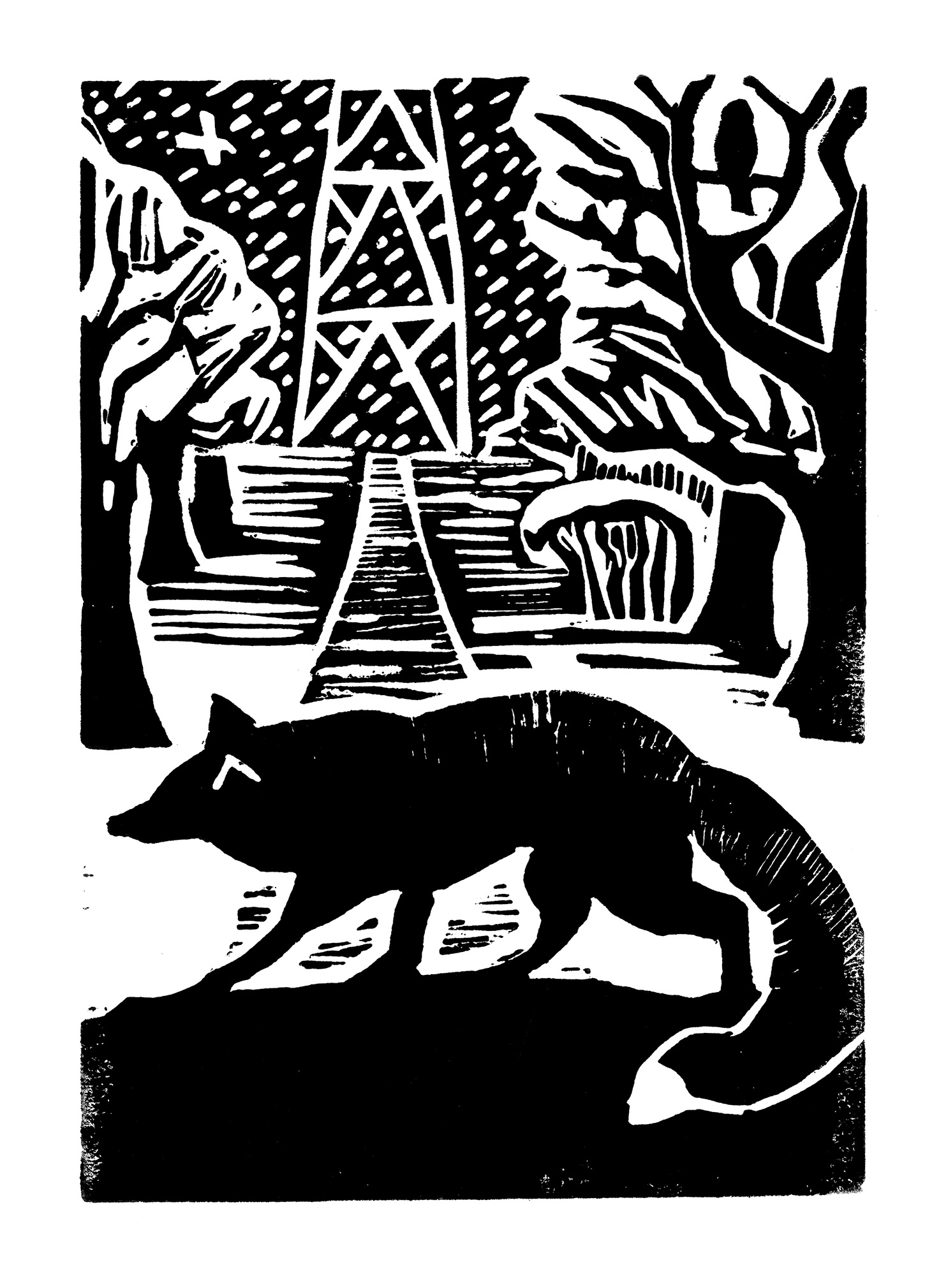

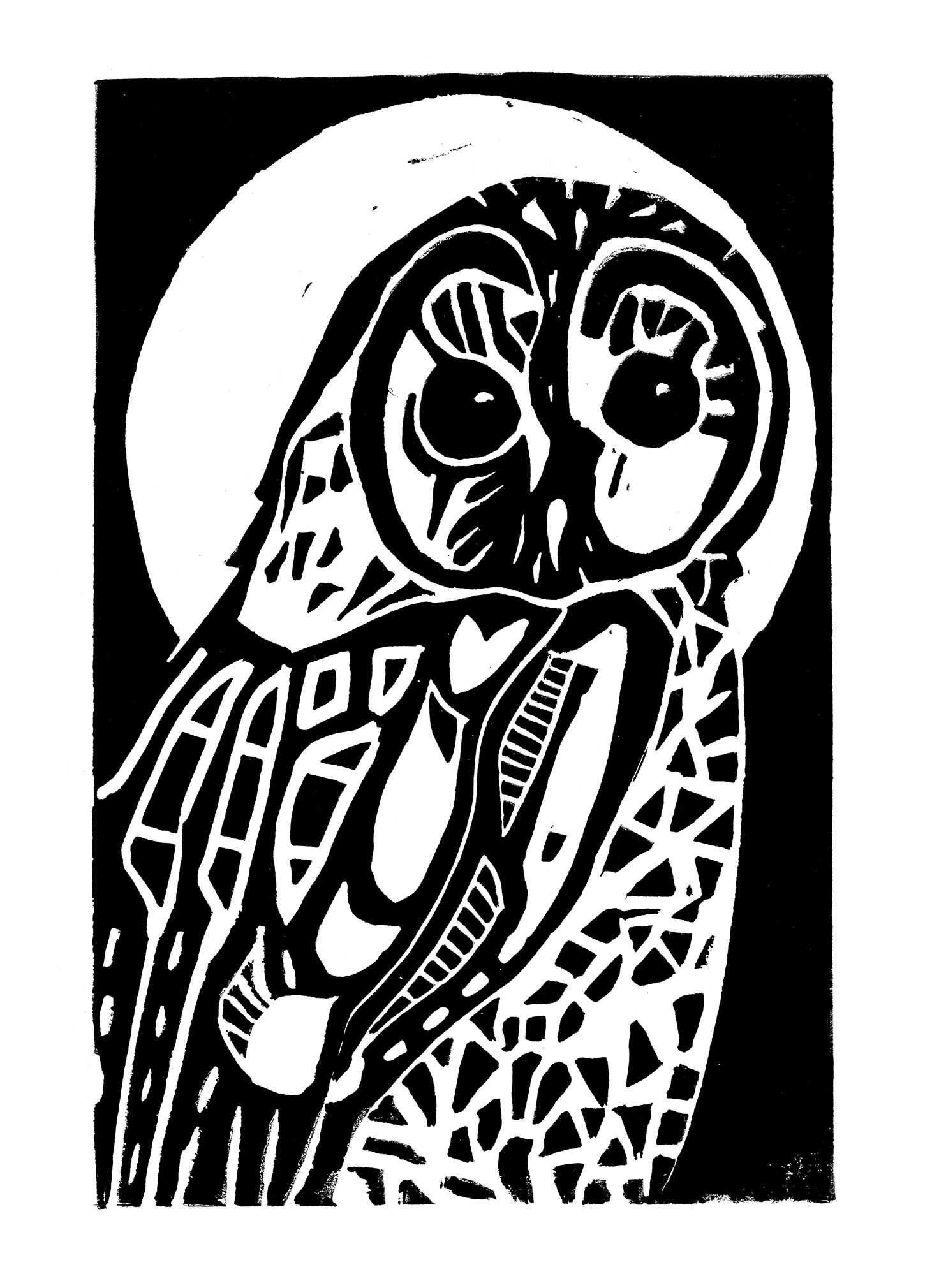

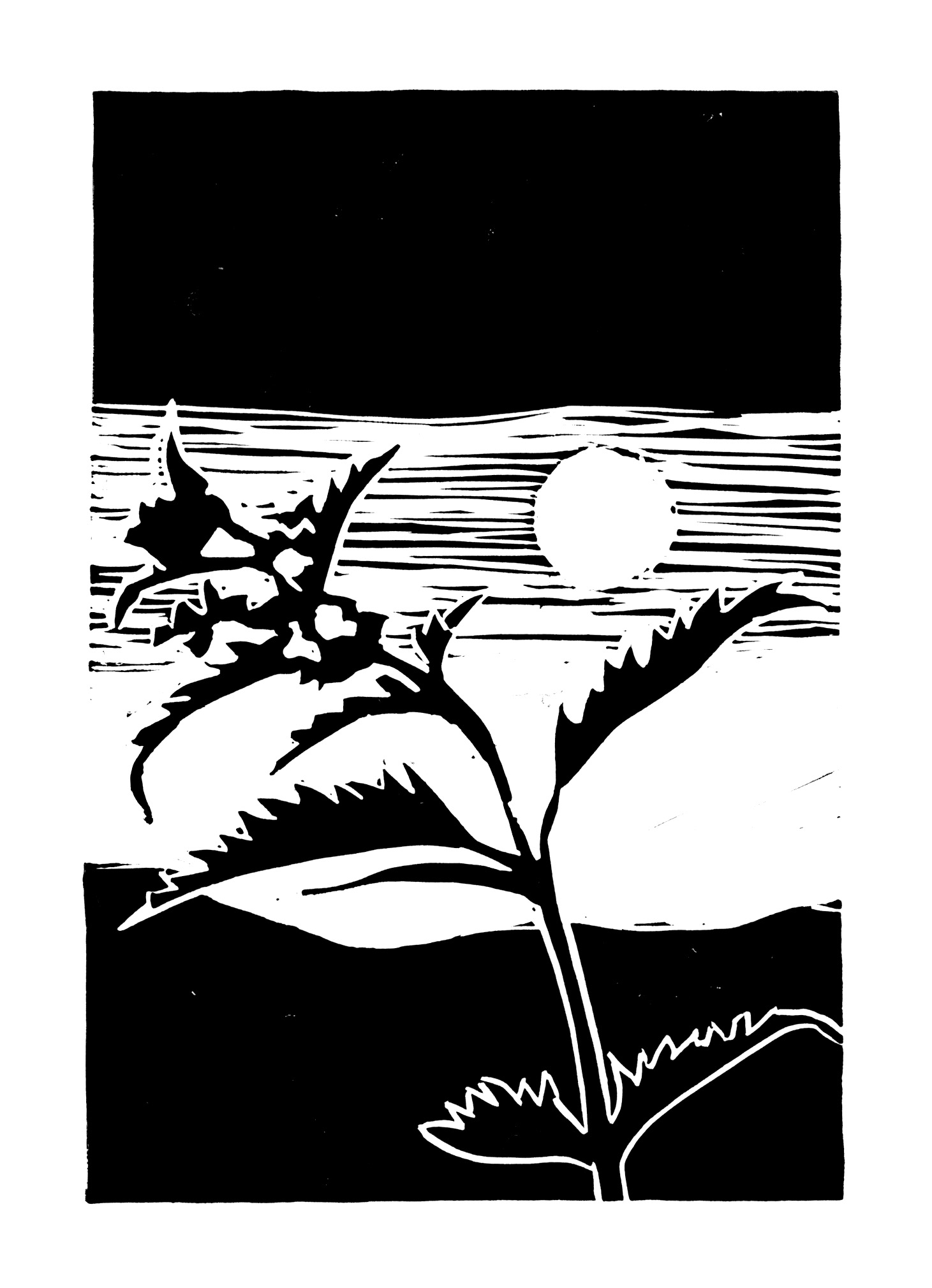

By half past five the light was little more than a blaze of red through the cruciform trees. Dark took the gorge unchallenged. Fallen branches were brittle as antlers but little repositories of life spotted every living shoot of tree. Rock-hard, egg-shaped and bright green, each was an assurance of spring, the promise of life lying dormant. Buds dotted a nearby oak branch. These were different: rounded, rust-coloured and massed in clumps at the end of each meandering twig. A tall beech had pointed copper arrowheads growing from its elegant curved boughs. Perhaps it was just the illusion of their fawn hue, but the leaning pines by the river seemed to retain the faint heat of the day so I hung about their trunks as the last glass bottle-blown notes of a woodpigeon faltered and ceased. Then the river glimmered with the echo of the owls. That extraordinary, aching call. Except it’s not ‘call’, singular. The famous tu-whit, tu-whoo of children’s stories is actually two birds communicating. The female utters less a tu-whit and more a ke-wick, but even this seems a poor transposing of her brief, piercing cry. Similarly, the male’s hoot is not so much a tu-whoo, it is more a syncopated hu ... hu-hulo-hooooo. Warmer than it reads. What the simplified reductions miss are the dexterous parts, the deft little trembling descent at the end like a folk balladeer adding emotional gravitas.

Such vocal attention to detail is hardly surprising. Sound is everything to tawny owls. They exist in loose communities but there are strict rules about spacing and tenancy. Territories lock together as neatly as housing plots delineated by the Land Registry, but having no sense of smell (or Land Registry), theirs is a predominately aural world. Calls are territorial assertions – this is my hunting ground; this is my mate – and like a catchy chorus, they are infectious. Hooting leads to hooting. In the pauses between them, I could hear the faint echoes of other pairs coming from downstream and from the west towards the meadow and town. I imagined the vast linguistic conversations that must flow out, around and across our night-drugged world, the silvery webs of chatter via which disputes are settled and breeding determined.

Books tell us that precisely in the same way we can recognise a change in tone in the voices of friends or family on the phone, owls living in proximity know one another through minute differences in vocalisations. Should a male fail to respond or its call sound weak, word will get around and its territory quickly snatched in a coup of chasing and hooting. But their singing is erotic too and, in established pairs, a male’s crooning stimulates ovulation. The two I could hear had almost certainly paired in the autumn and were probably well into the feathery tangles of mating. Or perhaps even past that, relaxing through post-coital rituals of preening, rest and roost, pressed up flank to flank by their nest site. There’s a softening in behaviour after copulation, a shift away from the talon-flashing late-night flirtations towards mutual trust and friendliness. Maybe the calls I could hear weren’t dirty talk; they’d moved on to rowing about kids, mortgages and money.

Although I didn’t see or hear it move, the male’s calls were suddenly directly above me in the black crown of a pine. I’d never heard an owl as clearly or closely, at the level of valves and throat vibrato, of air being worked to an owl’s purpose, but I couldn’t stay much longer. My own mate was calling; Rosie had been at home in bed for two days with sickness and exhaustion. Now she wanted feeding. The text request was unequivocal: ‘please bring pizza’. It didn’t sound much like the flu to me.

'Remember all of this, I told myself. Remember this ethereal quiet and the lines of melting snow streaking down the glass. Remember the heat of Rosie’s happy tears dampening my shirt.'

A coincidence: snow fell the exact moment I learned I was to be a father. And in that moment everything changed. Entranced by a blue line emerging in the little white window of a pregnancy test, we looked up to find snowflakes pouring into the street as if tipped from the back of a truck, obscuring where the horizon meets the grey roof slates of the terraces opposite. Then we lay together on our bed and watched the snowstorm form. Squalls of silent white swarmed the glass then backed away; flakes doubled in quantity, thickening into conjoined masses like cells dividing. The town was soundless; traffic frightened and slowed. Remember all of this, I told myself. Remember this ethereal quiet and the lines of melting snow streaking down the glass. Remember the heat of Rosie’s happy tears dampening my shirt.

After a while, a burst of laughter from guests downstairs popped our bubble. Suddenly our house was filled with life. Friends from London had booked to come up weeks earlier before any of this was on the cards. It was too early to tell them so we pretended our giddiness was down to the snow and suggested a walk in the blizzard. Half an hour later we were wrapped up and battling down Bilton Lane past houses that looked offended by the covering, like pensioners on their way to church unexpectedly caught up in an impromptu foam party. Cars were crippled. The wind rushed low and fast from the north and sent waves of snow upwards so that the storm appeared to be emanating from the edge-land. A sky of white tracer and the land beyond thick and grey as putty. It soon reached its zenith, though, and waned as we reached the crossing point. The familiar topography beyond formed slowly, as if through a demisting shower screen, then the low clouds flared with sun and evaporated into sky. Suddenly, in every direction, there were two tones: the linen-white of fresh fall and the coalblack of under-tree and under-hedge. Chaffinches struck up from hazels as we squeaked up the lane through virgin drifts. From the high rise of the fields the sun spreading over the distant reaches of the landscape made my eyes ache, but I fancied I could see further than ever, an effect wrought by this great levelling. All bumpy ground was smoothed; there was a new coat of paint. Everything clean and clear.

We let the others go ahead and stopped at a gap in the hawthorns at the holloway’s entrance. The edge-land was still new to Rosie and the view had rooted her to the spot. I put my arms around her, over her stomach, and my head on her shoulder so our faces were side by side looking at the same things – the lone oak, the razor-cut line of hills, the pylons, the smothered steeples, domes and towers of town. My mind raced with the power of nature inside and out; joy swelling and fluttering my stomach, happy as a man can naturally be. But it came with worry. I couldn’t shake the thought of how easily things can go wrong. ‘Wrong’ is not the right word, right and wrong being human concepts; what I mean is the sense of how things sometimes turn out differently from what we hope. Nature is impervious to wishes. Cells fail. Life wanes just as suddenly as a snowstorm. I said none of this, of course, but stood there taking everything in. What I remember most is the sound. The sheer, beautiful absence of it.

Turns out that sound is a pretty important part of the twelve-week scan. They don’t tell you that; the emphasis is always on what you see rather than hear, but the probe is a microphone too. Rachel leans forward, flips around the larger monitor and turns up the volume. The speakers cut in with a hollow cuurrrrrr – the static of a detuned radio or far-off industry, like the idling sewage works heard from the viaduct. Rosie’s grip on my hand tightens as the probe sits tail up in the air, nudging into her stomach. The sound becomes louder and punctuated by a quick, pounding, sluicing rhythm. A heartbeat: woosh-woosh-woosh-woosh. The whole thing is weirdly machine-like; I think of Second World War films when you can hear a ship’s propeller approaching from inside a submarine. On screen, the grainy silver- black sea resolves from owl into a little skin-skeletal shape lying horizontally with a pounding triangle in its centre, its weeny bone legs bent up to its chest.

‘Can you see the hands?’ Rachel asks as she highlights and zooms in. Not really, just a tiny, sleep-twitching fist covering the head in a boxing defence. Then it moves, shifting around onto its side as if trying to get comfortable in bed. This is what we will both remember: staring goofily at its incessant wriggling, a tiny quicksilver ghost messing up the bedclothes.

Along the hospital road, the white and pink cherry blossom is coming. There are spears of snowdrops in the gardens. I didn’t see them on the way there. The world smells cleaner. I confess to Rosie about seeing the owl in the ultrasound and she smiles. Later she says, ‘Why don’t we go down to the edge-land again? I’d like to hear the owls tonight.’