- Home |

- Search Results |

- Twelve Nights by Andrew Zurcher

Twelve Nights by Andrew Zurcher

Kay's father is working late - as usual. Fed up, Kay’s mother bundles Kay and her sister into the car to collect him – as usual. But when they arrive, nobody knows Kay’s father’s name and there isn’t a trace of him anywhere – and that was the moment that Kay’s life became anything but usual...

1. Removals

The sun set at six minutes to four. Kay lay stretched out on the floor, reading the very small print on the back of the newspaper. Her right eye she had squeezed firmly shut; her left was growing deliriously tired, and the tiny words loomed at her amid the blur of her sinking lashes. More and more she had to close them both, and relax her stiff cheek. More and more she squinted sidelong up at the world, with her head cocked to the right. But if her game caused her irritation, she also felt a sense of modest triumph: she had resisted the temptation to look straight at life since the moment she woke up that morning – exactly eight hours before, according to her watch. Had anyone asked her why she was still keeping her right eye shut at thirteen minutes past four in the afternoon of Christmas Eve, when her mother was going frantic in the back room and her little sister, Eloise, was careening around the house as a fairy-elf-in-the-box, she wouldn’t have known what to say. Keeping her right eye closed was simply something she had to do today, and she was doing it.

Just opposite her head, against the wall, leaned a large metal-framed mirror. Her father had promised to hang it above the fireplace, but three months later it still stood there, neglected, collecting dust. Kay regarded herself with curiosity in its dull glass. At school the teachers seemed to talk endlessly about character: having it, getting it, showing it and, above all, building it. Kay was sure she had none, or at least none that was visible. She was the person no one ever really noticed.

Her father was still at work – late, as he had been every day this week and every weekend this month. As he had been every month this year: down at the lab or his office, away for a fortnight on a dig, disappearing off to libraries or meetings – she couldn’t keep track. This morning Kay’s mum had wiped the worktops forcefully after breakfast, then promised her girls a bike ride and a trip to the cinema. But when the sun went down hours later, their winter shoes and coats still lay undisturbed by the door – exactly where they had left them the evening before. Kay could hear the telephone ringing, and she wondered if it was her father calling. He would be late, as usual.

Just as she was beginning to doze off, her head softly crackling on the open newspaper, her mother burst into the front room, her heels stomping like slippered hammers on the wooden boards. ‘Get your coat on, Kay, we’re going out. Get your sister’s coat on.’

Five minutes later, as they sat in the back of the car blowing steam in the freezing air and giggling nervously, the two girls still had no idea where they were going, or why. As the engine turned over from gear to gear, in rhythm with the car’s regular surges, their nervousness began to subside. Kay’s hand still held the warm ache where her sister had been squeezing it. She put it in her lap. The night outside the window seemed sharp and clear, and the mostly white lights in the houses they passed shone with a direct intensity. Her window, by contrast, kept fogging up with her breathing. She moved her face impatiently around the glass as far as she could reach, but it was no use. As the car jolted through some lights and then curved down the hill, Ell fidgeted with her foot.

‘Eloise, stop it. We’ll be out of the car in two minutes.’

‘But I have something in my boot. It’s uncomfortable.’

Kay turned to the window again. She counted the streetlamps as they passed, numbering them by their glows on the silvery ground, still frosty from the night before. Her left eye was now growing ridiculously tired – or maybe it was the funny flatness of seeing with just one eye – because in the centre of the circle of light cast by every lamp she was sure she could make out a little circular shadow on the ground. Maybe it was just the wisps of foggy breath still clinging to the glass. She was tempted to open her other eye to check – but then, she thought, if she did, and the little dark circles were gone, would that prove that they weren’t there, or that they were? Sometimes when you looked right at a star, you couldn’t see it; but if you squinted or looked away, you could. And stars were there. Otherwise how would you wish on them?

And then, all at once, she knew where they were going, and why her mother hadn’t answered her questions. The car pulled up and stopped outside the familiar gate. Kay went rigid in her seat, feeling her spine arch cold against the comfortable scoop of the fabric behind her. For her part, Ell was obviously disappointed. ‘I don’t want to go to Dad’s work,’ she whined, and kicked her grumpy and uncomfortable boot for emphasis against the seat in front of her.

A night porter sat on duty behind the window at the gate: an old, solid man, stiff and knotted as a fardel of wood, with a curve to his thick back and a white handlebar moustache hanging over a square-set jaw. Kay had never seen him before, but as he shuffled to his feet she recognized the white shirt, black trousers and waistcoat as the uniform of the university’s porters. The gate opened, and he waved them through into the empty car park, but then hobbled out of his dimly lit room, down the steps and after the car. He seemed to guess where they would park, because Kay saw him making directly for the spot as her mother doubled round a set of spaces and then reversed back in. He moved with a deliberate and stilted pace, but he still got there just as they were opening the doors. It was a soft voice he had; not the sort of rough bark common to university porters. Maybe he had been to a Christmas party, Kay thought. People were always gentler after a Christmas party.

‘Can I help you?’ he said to Kay’s mum. His voice sounded the way a flannel felt – dense, light and warm – and to Kay it was like a kind extended hand. Yet he stood with his hands dug in his pockets, his fingers working slowly within the fabric, as if turning over coins.

Kay’s mum was pulling Ell off the booster seat, then checking the little purple boot absent-mindedly. Ell was too old for a child seat now, and far too tall, but her eighth birthday had been a night of tears, and Kay and her mother had afterwards gone from room to room – and even to the car – carefully restoring old and familiar things.

Of course there was nothing in the boot, but her mother shook it out all the same as she answered the porter. ‘No, thank you. I’m just here to collect my husband. He’s working late.’

‘Everyone’s gone home, I’m afraid, Mrs . . .’ The man trailed off, and Kay watched him arch his bushy left eyebrow, expecting her mother to identify herself.

‘Clare.’ That’s because she doesn’t have Dad’s last name, Kay thought. She’s not Mrs anybody. ‘Clare Worth.’

‘Well, Mrs Worth, I’m not telling stories. As I said, I’m afraid everyone has gone home. The only cars still here are mine and old Professor Jackson’s that died Tuesday last, God rest him, and I’ve been round the halls to lock up, and the place is sealed proper and shut down tight, lights off and not even a mouse.’

Kay felt her mother’s arm tense where she was touching it lightly with the palm of her left hand. ‘I’m sure you’re right,’ she said, ‘but he did come down to work earlier, so I’ll go up and have a look all the same.’

‘What did you say your husband’s name was? Worth?’ The old porter sounded soft but insistent, like a wood pigeon maybe. He shuffled his stiff legs quickly to keep his balance. Kay thought for a second that he was almost smiling at the top left corner of his mouth, but then she changed her mind. Or maybe he changed his face.

‘More. Dr More. Edward, I mean. More. He’s a fellow at St Nicholas. He’s working on the Fragments Project.’

‘Well, I can’t say as I know the names of the projects,’ said the old man. ‘They come and go. But I got a pretty good head for the people, and I don’t think I recollect seeing a Dr More before.’ He drew a short breath, held his hands up to his face and blew hard on the tips of his fingers, trying to warm them. ‘But I’m just the night porter around here.’

‘Oh, you’ll definitely have seen him,’ Kay’s mum said. ‘He’s down here almost every evening. Every night.’

The porter told her he had a directory and a telephone, and he would save Kay’s mum the trouble by calling up to the office. She started to protest, but he had already hobbled painfully round and was walking back to his lodge. Eventually they trailed after him. Kay’s mother’s hand was cold in hers, but then it would be, in the middle of winter. They waited outside the steps of the tiny lodge – really just a bricked-in nook between two buttresses on the old archaeology building, with a lean-to roof and a pretty, circular window. The little window had silver stars stuck in it, and Ell pointed at them and started talking about a card she had made at school with stars just the same, and tinsel. She had repeated herself three or four times, to no effect, by the time the porter turned up again in the doorway. Kay tried to ruffle her hair, but it was drawn back over her scalp as tight as ice.

‘I’m afraid I can’t find Dr More on my list,’ he said. ‘In fact, I can’t find him on the university list either. Edward More, you said? I tried both spellings.’

Kay’s mum sighed heavily and, leaving the girls, went in. They were quiet enough under the window ledge to catch a few snatches of conversation from within. The car park, silent and empty except for the three cars the porter had pointed out before, had a few bare trees – saplings of four or five years’ growth – dotted at regular intervals down two aisles. Kay remembered that there had been grass here once, but now it was almost all paved. The tree branches glistened black in the bright spotlights from the roofs of the archaeology building. The Pitt, they called it. Kay squeezed hard on her left eye, plunging herself into darkness, and gripped Ell’s hand more tightly, as if to compensate.

When the door opened, the muted voices suddenly shot out and rebounded around the empty courtyard. Clare Worth was protesting again: ‘. . . don’t understand. I mean, I know you say it’s current, but he’s definitely here. He’s been here for years. I can show you the room.’

Kay heard the porter pick up his ring of keys, then pull the door shut behind them as they descended the three or four steps into the car park. Her eyes were still closed, and maybe that was why she heard the crisp echo in the courtyard so acutely, with its single clear report. Each step her mother took made a crack against the fresh stone and pavement.

‘What did you say your name was?’ Clare was asking the porter as Kay pried open her left eye again.

‘Rex. Just Rex,’ he answered with a wince. He stepped with a stiff hip over a low wall running round the inner grass border of the courtyard, and set off for the near corner where Kay’s father had his laboratory and office, on the second floor. Her mother shot him a sharp glance, as if he had just loosed a tarantula, but then – with more resignation – pursued him. She seemed to have forgotten all about her daughters. She didn’t speak again, but as she passed by, Kay could see that there were a lot of words in her throat; from the side it looked like it was going to burst open. She and Ell fell back and followed the two adults, holding hands and looking down, watching their footprints making tiny depressions in the frost, crunching slightly. Rex had a light step, Kay noticed, because although her mum’s new shoes ground visibly into the frozen grass, for all his rough limp and shuffle Rex’s feet didn’t seem to make any noise, and hardly any marks at all. All she could hear were his keys jangling on the big ring in his right hand. For a second, in the glare from the spotlights, she saw it very clearly, that ring of keys, and noticed that it had an old-fashioned locking mechanism, with a hinge to open it – like something she had seen at her father’s college once, hanging in the manuscript library. Only this ring wasn’t plain. She caught another view of it as it swung again briefly into the light. She made out two bits of carving or metalwork, one on the hinge and another on the hasp. She watched for it as they walked, and with glimpse after glimpse she pieced together the design. It was the same on both sides: a long and sinuous snake entwined with a sword.

He must have been in the army, she decided. He had probably been injured: the limp.

‘His room is on the second floor,’ her mother was explaining. ‘And his name is just here on the board – look...’ And then her voice trailed off, because, as they could all see – and they were all looking – his name was not on the black painted board, where it had always been for as long as Kay could remember, in its official white lettering, next to the others. Where his name should have been, the board instead said, Dr Andrea Lessing. Her mother pushed through the heavy swinging doors into the stone lobby, and the girls trailed after.

‘What’s wrong?’ Ell whispered to Kay. Her voice was sharp, urgent.

‘This is some kind of joke, girls,’ said Clare Worth, forcing a smile at them. ‘It’s a joke, that’s all.’ She took out her phone and dialled. ‘I’ll try the office again,’ she was saying. ‘There was no answer before, but maybe he’s back now.’ And then her face went white. ‘Stay here,’ she said, her voice suddenly pinched almost to a whisper. Turning, she practically leaped up the stairs.

Kay looked at the ring of keys. She stared at it, at every small detail, one after another, taking them in.

Rex noticed her staring, smiled, unhooked it from his belt and held it out to her. ‘Have a look if you like,’ he said with a warm half-chuckle. He passed her the whole set. His hands were big and gnarled, like the rootball of an oak. She observed them as she took the keys: oafish but gentle, and somehow slender, too, and as he stretched out his fingers she thought she smelled something sweet, like soft fruit – maybe blackcurrant. But then she had the ring. It held an amazing collection of keys. Even Ell came over to look, which was unusual because she tended to make a point of being officially uninterested in whatever Kay was doing. Kay handled them one by one. The best was an enormous key that looked like a fork, with sharp tines, and seemed to be made of gold. It had the same snake and sword cut into it as the ring. And there were three silvery keys, each slightly different from the other, but all with the same kind of shape: a long shaft, with a flat bit fixed at the end – one was square, one circular and one triangular. There were three wooden keys, too – but hard wood, almost like stone, with a gorgeous gold-flecked grain in them. And there were others, short and long, stumpy, heavy. There might have been twenty or thirty of them.

‘Stupid keys,’ said Ell, and she turned towards the full-length mirror that hung against the lobby wall, studying herself. Kay and the porter – Rex – watched her, too. That faint smile was hovering at his cheek again; like Kay, he knew that Ell didn’t mean it. Her sister was shorter than Kay by a hand or more. Where Kay was olive-skinned and chestnut-haired, Ell had bright, almost translucent skin, and undulating tresses of a fine, almost golden red. Their father was fond of remarking that their family was composed of four elements. ‘Your angel mother is the air, as open as the sky. I am the hard and plodding earth,’ he would say, ‘but you girls are the quick matter of the world.’ Kay, he said, was water: silent, deep, cold perhaps, but quick with life. Ell, by contrast, was fire, hot and unpredictable, both creative and destructive.

Moody, more like, Kay thought. And she smiled, despite herself.

She looked at the grandfatherly porter and thought she should try to be polite. ‘What are they all for?’ she asked.

He was still watching Ell. ‘Nothing of any consequence now,’ he answered. ‘Just look at that beauty,’ he added, almost as if to himself. ‘I’ll wager she won’t need any keys at all.’

Taking the steps two at a time, Ell had begun to jump up the spiral staircase in her fur-edged purple rubber boots. They were a little too big, a hand-me-down gift from Kay which she had not yet quite grown into. They made her seem smaller than she was; clumsy, a little delicate. At the fifth or sixth step she turned round, grinning impishly, her face flushed and radiant after the cold air outside, her full lips pink and puckered.

It is sometimes the case that something exceptionally beautiful happens just before a calamity. The calamity even seems to reach back in time and twiddle the beautiful thing round, making it even more beautiful because of what was about to happen – or anyway, Kay thought a few moments later, that’s how it comes to seem.

Ell looked so beautiful standing there, her lips grinning and pursed at once, her eyes dancing in the light from the lantern in the centre of the lobby, her radiant red hair now loosely draped across her shoulders, her whole form alight with daring and mischief. And then she started to take a step in those big, stupid purple boots, and tripped, and fell, and her face hit the stone floor first.

In the gap before she could cry out, the porter, Rex, jumped to his feet and sprang lightly over to her. He reached down, lithe and strong, and caught her up. The movement was sinuous, the spring and cradle entirely balletic. Kay hardly had time to breathe before he was sitting down again, the whole sobbing form of her sister tightly, snugly nestled in his arms. She watched, at once shocked and mesmerized. For her part, Ell settled into Rex’s arms as if he were a hearth.

Slowly he rocked her; slowly the little girl’s sobs subsided. Kay noticed she was gripping Rex’s keys so hard that her hand had turned white; a piece of sharp iron had made a welt on the edge of her palm. She held them out. The noise shook Rex from something like a reverie, and he looked up at her. Everything seemed to be happening very slowly. Ell sat up on his knee, as if awaking, and she, too, looked at Kay. Rex took the keys. Still he stared. And then Kay saw it: a perfect symmetry between the old man and the little girl – as if cut from a single stone by the same hand, as if painted in the same colours, as if sung by the same singer, they regarded her with their heads at an angle, their eyes at one focus, their mouths equally parted. All was equal. Kay froze.

‘Sometimes,’ Rex said slowly, somehow at once both fulfilling and breaking the spell, ‘something exceptionally beautiful happens just before a calamity.’

Every hair on the back of Kay’s neck stood up, but not in fear. His eyes were too kind for that – as if they were the eyes of her own sister. Sometimes, somehow, something.

Just then Clare Worth came running two at a time down the spiral stairs. She sprinted past them, out through the double doors and into the courtyard. Rex set Ell on her feet, then, with some deliberateness, put his hands on his knees, pushing himself up. Hooking the keys back on to his belt, he held the girls’ hands, and they walked after Clare Worth as quickly as he could. A few minutes later, safely belted in the back seat of the car, both girls turned as their mother – oblivious – pulled out of the Pitt car park. They were still stunned, watching for the old man on his step. He stood there, looking, Kay thought, like a man composed all of sadness, like someone condemned for a crime he did not commit. His hand was raised in farewell.

It was the same at St Nick’s. No one seemed to know Edward More there, either; and the college room where Kay had spent her half-term holidays, looking impatiently out of the window at the afternoon activity, had someone else’s name over the door. In fact, it had the same name over the door as that on the board in the Pitt: dr andrea lessing. Only this time the light inside was on, and the woman who answered Clare Worth’s knocking appeared to be as surprised as they were. She was tall, but also somehow small and delicate, and Kay thought her bones were probably as thin and wispy as her gold hair. She was wrapped up in serpentine coils of scarves and throws.

‘I have no idea what you can possibly mean,’ she said. ‘I’ve had these rooms for the last fifteen years. I’ve never had any other rooms for as long as I have been at St Nick’s. Have a look round,’ she continued, stepping back from the door and gesturing around the room with fine, elegant fingers. Kay thought they looked, each one, like nimble snakes, writhing with venom and muscle. ‘These are my books, my things, my work.’ Kay’s mum had been frantically explaining while two porters hovered nervously on the stairs behind them, unsure whether to intervene. ‘I really can’t help you,’ Dr Andrea Lessing added. ‘In fact, I was just about to go home for the holiday.’ She started to close the door, but Clare Worth had seen something, and she wedged her foot firmly in the way.

‘I don’t know you,’ she said accusingly. Kay shrank from the menace in her mother’s voice.

‘I am sorry for that, but I hardly think it’s my fault,’ replied Dr Andrea Lessing.

‘Are you an archaeologist?’ Clare Worth’s eyes moved more wildly now, ranging around the room, trying to make out the titles of the books just to the left of the door. The light was low. Kay noticed that her own leg was shaking, so she pressed her foot hard into the floor of the staircase. ‘I see you have some of the same books my husband has,’ she said. ‘Many of the same books, in fact. Do you work on the Fragments Project?’

‘Mrs More –’

‘My name is Worth.’

‘Mrs Worth, really, I’m sorry, I don’t have time for this. Yes, I do, but no, I really must ask you to let me close the door and get home to my family.’ Dr Andrea Lessing was pushing the door. Kay’s mum’s foot was sliding back on the wooden boards. Then her heel hit the ridge where the raised lip of the door-frame blocked the draught. Her foot held. There was an awkward silence, and the porters started to shift, leaning forward as if about to intervene. Kay drew a breath and raised her hand to reach out, to touch her mother on the shoulder or at the vulnerable place at the tip of her elbow. She wanted to get her out of this place. Instead, Ell’s hand shot out and took hers; her face was fierce and full.

‘Do you know about the Bride of Bithynia?’ It was her mother’s most level, grave, but also, now, desperate tone.

Kay knew it the way she knew how the stone outcrop behind her house felt to her knee when she smashed down upon it with her full weight. She knew it as well as she knew the tread of the stairs to her room, the soft click of the door’s latch behind her, and the comforting, lofty quiet of her top bunk. And she knew that the diminutive Dr Andrea Lessing had to be pushing with enormous force, because this door suddenly slammed shut on her mother, knocking her back on to her left foot and very nearly crushing Kay and Ell against the cold and flaking plaster of the stairwell.

Clare Worth looked dazed, her daughters not less so. The porters were clearly distressed and apologetic. For some reason they could not explain or understand, they felt a sympathy for Clare Worth, whom they knew they knew, though they couldn’t say the first thing about Edward More. They kept saying so to one another in muted tones as they walked back through Sealing Court. Clare Worth seemed to have given up trying to understand. The porters held the door for the girls as they stepped through the wicket of the Tree Court gate, back into Litter Lane, where they had distractedly ditched the car half an hour before. With gingerly moving fingers the two men ushered the gate closed behind them, as softly as they could, trying not to give the impression, Kay thought, that they were shutting them out. But they were shutting them out. And the moment the lock clicked, Kay’s mum began to cry. She didn’t move from the gate or put her hands to her face. She just looked down. The only sound Kay could hear was a ventilation fan up the alley, pumping steam and the smell of grease out from the college kitchens. Ell shivered at Kay’s light touch.

‘Mum,’ Kay said.

‘Yes, Katharine, what?’

‘Mum, there was something strange about that porter at the Pitt. Rex.’

‘What, Katharine?’ She was still crying. Clare Worth didn’t sob when she cried, but the tears now came quickly and heavily.

‘Well, for one thing, when you were walking up to Dad’s office – well, what should have been Dad’s office – and the courtyard was really quiet, your feet were making a lot of noise on the stone, and you were leaving footprints in the grass. And so were we. I checked.’ Ell had been kicking a cobble. Now she stopped.

‘Yes, of course, Kay.’ Clare was reaching in her pocket to find an old tissue, which she laboriously picked apart and flattened. She sounded annoyed. Kay took and squeezed Ell’s hand while she waited, but Ell pulled it away and stared hard at her sister, as if to warn her off, to make her stop. Ell was always telling her not to bother Mum, not to stick her nose into other people’s business.

‘Well, you know how that old porter had a limp or something? And he walked heavily? But he didn’t leave any prints on the grass, and I don’t think I could hear his feet on the cobbles at all.’

‘Katharine.’ Clare Worth exchanged the tissue in her hand for the keys in her pocket and unlocked the car. ‘That’s the very least of my worries right now. Something horrible is going on, and footprints in the frost don’t matter. Not at all.’ She stood up and bore down on her daughters with newly hardened eyes. ‘Now get in.’

In the back of the car, Ell’s face was wearing that fierce look again. ‘Told you,’ said her eyes.

So Kay didn’t mention the other things on her mind: Ell’s fall, the strange kindness and familiarity of the porter, and something she thought she’d seen in the room at St Nick’s – what should have been her father’s room, but was the room of Dr Andrea Lessing. Something she had seen while her mother was being pushed back on to her left foot as the door closed abruptly behind the enormous strength of a very slight woman. Instead the two girls sat quietly and the car moved slowly, almost reluctantly, through the empty, dark streets, past the reaching winter spines of the chestnuts and the hawthorns and the oaks and the beeches and, above all, the countless lime trees, blacker than the visible light of the black night. And she didn’t ask about the Bride of Bithynia, and they ate their cold supper where it still sat on the plates Clare Worth had set out in the afternoon. And because of the tears that sometimes drew and dropped down their mother’s cheeks, the girls did as they were asked, or expected, and never once thought of their baubled and tinselled tree, unlit, or of the wooden box that contained their stockings, which in the past they had always hung from the mantel on Christmas Eve. And they never once dared open the door of their father’s study, for fear of the emptiness Kay was sure (her ear pressed to the door’s painted wood) would lie within it – the vacant shelves, the cleared desk, the stacks of papers that would not stand there on the floor where they had always stood before. The girls never once uttered a single word. Instead they brushed their teeth, and they dressed for bed, and they turned off the light. And all the time, without speaking at all, Kay kept her right eye shut, and Ell picked at her hands, and Clare Worth wiped those occasional tears from the bottom of her jaw on the left side, so that they didn’t drip on her blouse.

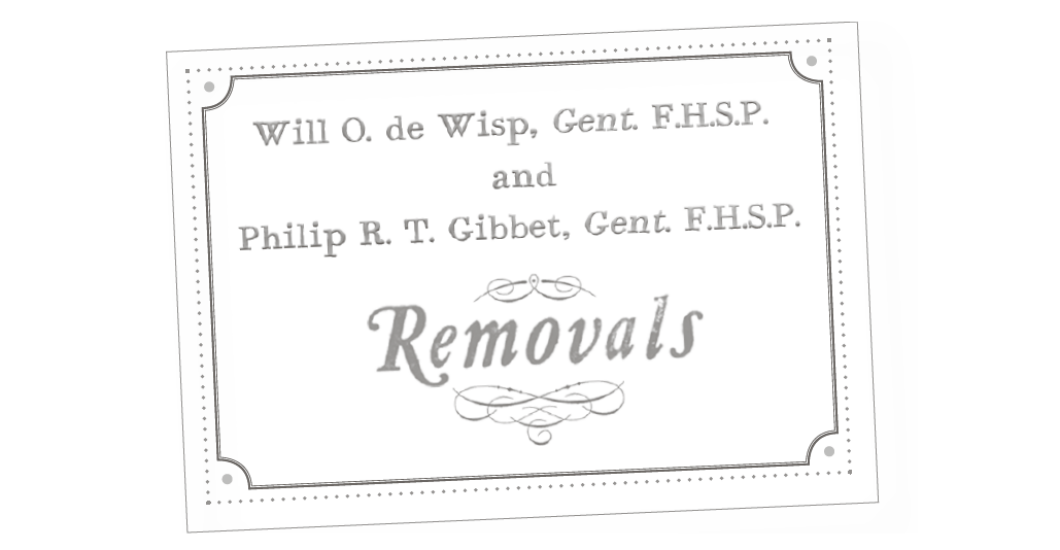

But when Kay climbed up into her bunk bed, she felt something on her pillow. It was a card. She knew at once that she hadn’t left a card on her bed. It was small and stiff, about the size of the train tickets they sometimes got when Mum took them to Ely for a summer picnic. Kay held it up. She couldn’t read the writing at first; but a light shone from her mother’s room, where – uncharacteristically – she was sobbing a little, and a shaft of it, shooting through a crack in the door, caught the card as Kay turned it. Then the silvery letters leaped out, glittering in her hands. It read:

Kay was exhausted, and below her Ell had as usual fallen asleep the moment her head hit the pillow. Listening to her deep breaths made Kay the drowsier, and she looked more and more vacantly at the strange card as it clung to the light in her weakening hand. Just before her left lid finally collapsed, and just as her hand was dropping out of its shaft of light, she might briefly have glimpsed the other side of the card, with its carefully stencilled and embossed silver emblem – the very symbol that, an hour before, she thought she had seen on a book lying on Dr Andrea Lessing’s wide wooden desk; a symbol she definitely had seen several times that day: the body of a snake entwined with the blade of a sword.