What ‘Disgrace’ was telling us before we were ready to listen

I can still remember, fifteen years ago, walking through the frost-bitten campus trying to escape the feeling of horror left in me by J. M. Coetzee’s Disgrace.

It was 2005, my first year at university, and the same dog-eared copy that was stuffed into the back pocket of my jeans that day has sat, untouched, on the bookshelf of every home I’ve lived in since. It’s not that I ever forgot about Disgrace. On the contrary, I thought about it strangely often. It was more like a feud I felt unable to resolve.

The novel follows David Lurie, a middle-aged English professor in Cape Town who has an affair with a younger student, Melanie. After she breaks it off and makes a formal complaint to the university, David is – partially through his own refusal to apologise, like a sort of inverted John Proctor – exiled from his job, and goes to seek refuge on a small farm owned by his daughter Lucy.

It’s there, in the baking South African heat, where Disgrace's most cataclysmic scene takes place. Returning from a walk, father and daughter are stopped by three strangers who break into their home and attack them. While David is locked in a toilet, Lucy is victim to a terrible sexual assault for which she can never seek justice, thanks to indifferent authorities and her complicated relationship with a neighbour whose complicity in the event is never fully revealed.

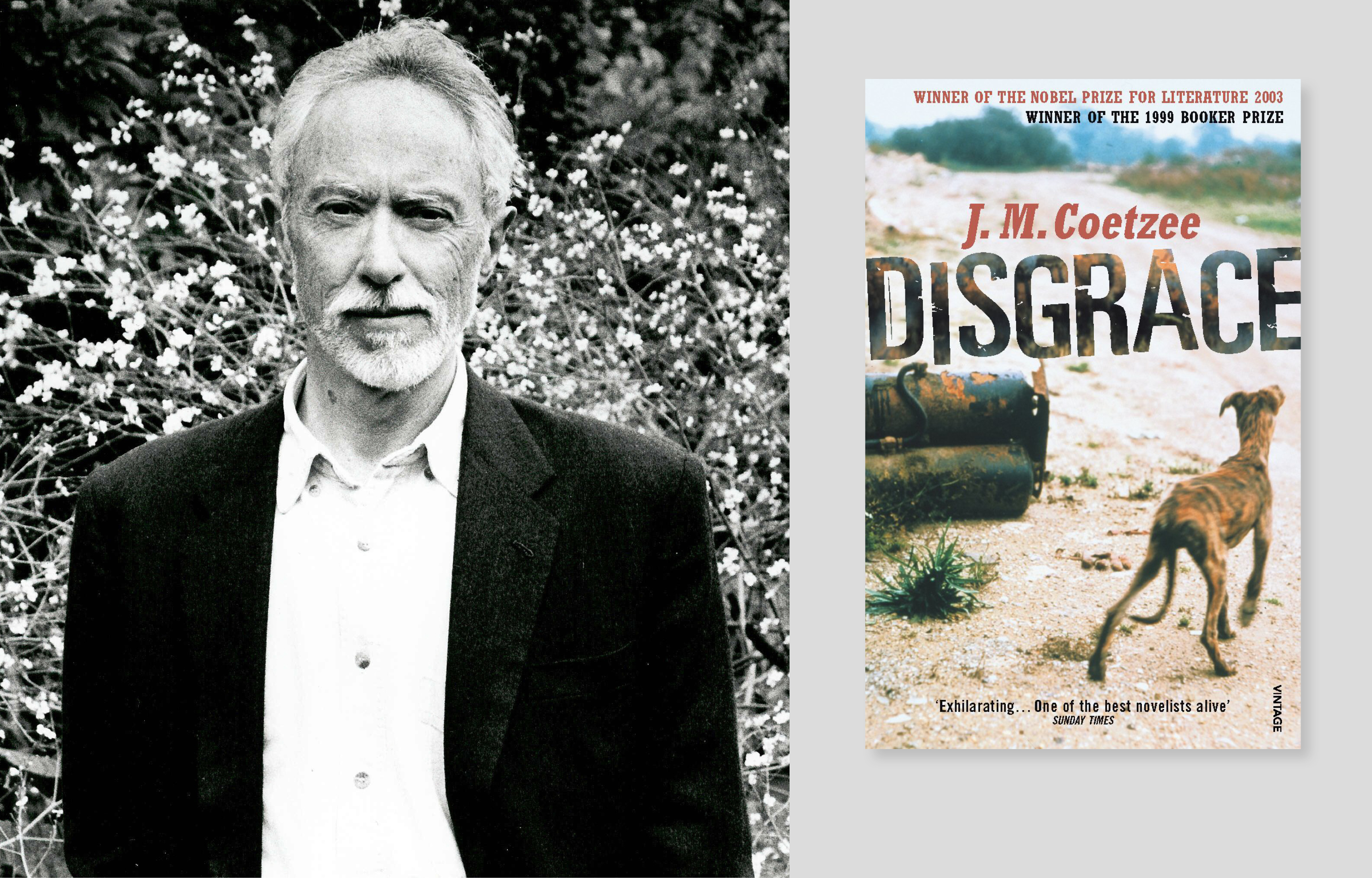

'Twenty years on, the prose is no less startling.'

Disgrace won Coetzee both the Booker Prize in 1999 and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2003. Returning to it this year, the mastery of plot (somehow, it is only 220 pages long) and the perfect weight of his prose are no less startling. That propulsive, disorientating scene in particular, so vivid and haunting in its details – the grass in a shoe viewed from the floor, the splash of toilet water over singeing hair, the youngest of the attackers gleefully scooping ice cream from a tub – is a masterpiece within a masterpiece, a writer at such peak powers the book seems to tremble slightly in your hands.

It wasn’t just what happened to Lucy that disturbed me the first time, but David’s utter inability to comfort, understand or avenge her. The novel is told very much from his (old, white, male) perspective, and the final pages are a portrait of a man so utterly ineffective and out of step with the world he can find solace and purpose only in assisting in the euthanasia of stray dogs.

At the time of its publication, Disgrace was lauded primarily as a searing examination of racial tension and the legacy of apartheid in South Africa, a contemporary classic of postcolonial literature. After finally deciding to revisit it in 2020, I wonder if it might serve us just as well as a critique of male entitlement. In a post MeToo world, the first half of the book, which follows David’s manipulative pursuit of a student several decades his junior, seems just as harrowing as the events on the farm.

After accosting Melanie on campus, David invites her back to his flat where, to strains of Mozart, he insists she drinks wine and pontificates about Wordsworth before, inevitably, forcing himself onto her with a kiss. ‘And passions? Do you have any literary passions?’ he asks, to which Melanie replies: Adrienne Rich, Toni Morrison and Alice Walker. He simply ignores her and starts banging on about The Prelude again.

'Lurie is one of the least likeable protagonists in literature.'

The comic irony of Melanie listing writers David could stand to learn a lot more from than the long-dead Lake poets he venerates is followed quickly by a far more disturbing scene, in which he forces himself onto her again, this time to have sex:

She does not resist. All she does is avert herself: avert her lips, avert her eyes[...] Not rape, not quite that, but undesired nevertheless, undesired to the core.

Back in 1999, the Irish Times summarised this part of Disgrace’s plot by saying: 'Lurie's fall occurs when he forces his attention on a young woman student, who though initially complicit, soon retreats into a disengaged curiosity.' The Independent, meanwhile, declared the book 'concerned with the itch of male flesh', which makes it sound almost like David was the true victim. It reminded me of the way, just a year earlier, 22-year-old Monica Lewinsky was been portrayed as a femme fatale who brought down a helpless president. How far we’ve come. It seems unlikely critics today – or undergraduate students, for that matter – would interpret Melanie’s behaviour, still less an oxymoron as galling as ‘not rape, but nevertheless undesired to the core’, with anything approaching ambiguity.

That Disgrace now seems prescient about the re-examination society is undertaking of our attitudes towards sexual assault, and the experiences of younger women with older, powerful men in particular, is no accident. David Lurie is, to my mind, one of the most unlikeable protagonists in literary history, as self-pitying as Victor Frankenstein, as lacking in empathy as Humbert Humbert and as pompous both. But crucially, Coetzee allows him almost nothing in the way of salvation. He ends the novel professionally and personally chastised, utterly ruinous and barely any more self-aware. Instead, his disgrace feels inextricable from the way he minimises Melanie’s voice and experiences and stomps over Lucy’s in the throes of a misplaced saviour complex. Looking back at the parallels Coetzee draws between Melanie and Lucy, it’s clear he wanted us to consider what happens to them in the same terms, even if, like David, we weren’t all ready to back in 1999. Like most literary masterpieces, Disgrace's power seems to be shifting with our times. It is still lurking, like the dog on its cover, at once menacing and pitiful, and with plenty to show us should we have the courage to face it head on.