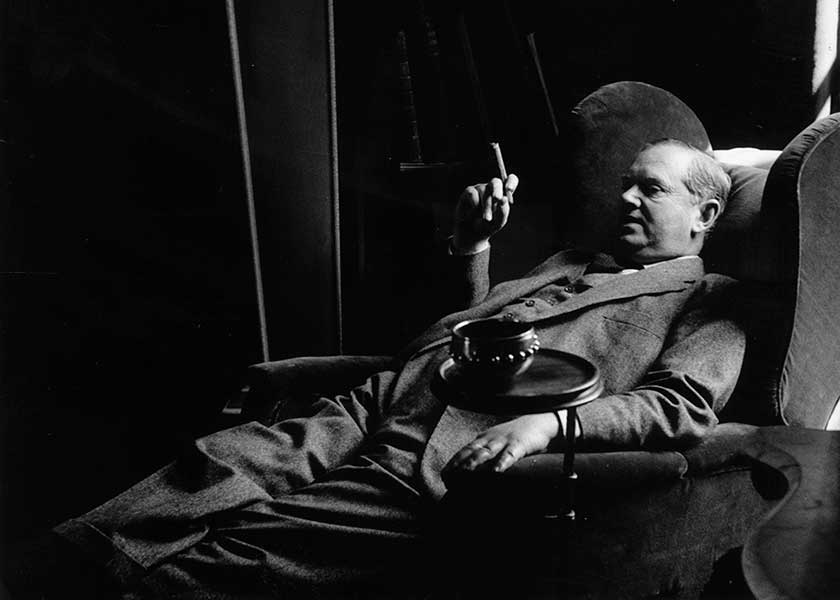

Beyond Brideshead: why Evelyn Waugh needs to be reclaimed as our funniest writer

Sharp, sparkly and endlessly versatile, Evelyn Waugh's overlooked novels make him the perfect choice to cheer us all up, says John Self.

Why read Evelyn Waugh now? Wasn’t he a crusty old conservative snob? Well, up to a point. The writer that Graham Greene called “the greatest novelist of my generation” remains widely misunderstood, though perhaps not as badly misunderstood as when Time magazine in 2016 listed him as one of the 100 most-read female authors in US colleges.

The first reason to read Waugh now is that god knows we all need a bit of cheering up. Waugh is very funny: sharp, sparkly and biting. He made laughter out of school and university (in Decline and Fall), the newspaper industry (Scoop), and even – this might ring a bell – a dysfunctional government at a time of national crisis (Put Out More Flags). Who could be more timely than a writer who, on the very first page of his first novel Decline and Fall (1928), mocked Oxford University’s boorish Bullingdon Club, which gave us two of our last three Prime Ministers? In Waugh’s world it’s called the Bollinger Club:

'Quite often the club is suspended for some years after each meeting. [...] At the last dinner, three years ago, a fox had been brought in in a cage and stoned to death with champagne bottles. What an evening that had been!'

'He is, tragically, famous for Brideshead'

Waugh’s comedy was primarily satirical, mocking the great and good in society, from the newspaper magnate Lord Copper in Scoop (1932), whose foreign editor is so fearful of him that instead of saying 'No' he says 'Up to a point, Lord Copper', to the bright young things of 1920s high society such as fiancées Adam and Nina in Vile Bodies (1930) who succumb to the increasing sexual openness of the time: 'All this fuss about sleeping together,' says Nina. 'For physical pleasure I’d sooner go to my dentist any day.'

Vile Bodies, perhaps Waugh’s funniest book, is 90 years old this year but shows none of its age. That’s not just because of Waugh’s crisp prose and sparky dialogue, but also his modern approach (he claimed that it was the first English novel where telephone conversations play a major part) and his concerns. Vile Bodies portrays shallow people who live life on the surface, a timeless subject that’s renewed every few decades by writers like Joan Didion, Bret Easton Ellis and Ottessa Moshfegh.

It’s possible that if you know only one novel of Waugh’s, you weren’t aware that he’s supremely funny, because he is, tragically, famous for the wrong book. His work is overshadowed by the monolith of Brideshead Revisited, his 1945 novel of nostalgia, aristocracy and Catholicism. It was given a boost by the mimsy 1980s TV adaptation – a soft-focus alliance of Jeremy Irons, Anthony Andrews and a teddy bear – and that legacy lingers, but even in Waugh’s lifetime it was his most popular book, which “led me into an unfamiliar world of fan-mail and press photographers.” But its popularity is hard to fathom to anyone who has read Waugh’s other, funnier novels. Brideshead is solemn and dreary, and the key to this is that it was written during the war, “a bleak period of present privation and threatening disaster,” as Waugh later commented. “In consequence the book is infused with a kind of gluttony, for food and wine, for the splendours of the recent past, and for rhetorical and ornamental language, which now on a full stomach I find distasteful.” Exactly so.

Indeed, it’s Waugh’s usual care for language that makes his best books so funny and piercing. “I regard writing not as an investigation of character but as an exercise in language, and with this I am obsessed.” It is his obsession with getting the right words in the right place that makes his jokes funny, his plot turns shocking and – despite himself – his characters so affecting.

Nowhere is this seen better than in his most perfectly balanced novel, A Handful of Dust (1934), a tragicomedy about the luckless Tony Last, a man whose story spirals downward so thoroughly that his wife’s infidelity at the beginning is as good as it gets. As well as having an unforgettably bizarre and brave ending, A Handful of Dust confirms Waugh's genius as a stylist, proving, as writer Isaac Babel put it, “no iron can pierce the heart so chillingly as a full stop put in just the right place". To give specific examples would spoil the plot, but trust me, they're in there.

(A secondary example in this book of Waugh’s brilliance is the character of Tony and Brenda’s son, John Andrew. He is one of the most distinctively drawn children in literature but appears only through his speech; there is not one word in the book describing him.)

And yes, Waugh was an arch-conservative and a snob, partly through his peculiarly complex relationship to the upper classes, which he longed to be a part of but couldn’t. As a boy he used a postbox some distance from his home, so his letters would be sent with a postmark from Hampstead rather than Golders Green. And when the Honours Committee in 1959 offered him not his coveted knighthood but a CBE (an award he considered fit only for “second grade civil servants”), he crumpled up the letter and rejected the offer.

'Waugh is unlike almost every other major writer of the last century in that his work did not decline with age'

But as a comic writer, Waugh had a vast range: he was (with all due respect to dear old Plum) the P. G. Wodehouse whose books aren’t all the same. Waugh wrote a memoir (A Little Learning, which ends with his life being saved by a jellyfish), a dystopia (Love Among the Ruins), a comedy about the American death industry (The Loved One), and – a very modern idea, this – an autobiographical novel about his period of mental breakdown (The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold). He even, with great skill, illustrated some of his own books.

Above all, Waugh is unlike almost every other major writer of the last century in that his work did not decline with age. Indeed, many think his final work of fiction, the Sword of Honour trilogy, is his greatest achievement of all. It “should be read every year by every serious reader,” says novelist Patrick McGrath. Sword of Honour is fiction on a major scale about Guy Crouchback, a man in his mid-thirties who wants to sign up to serve in the Second World War: “I’m natural fodder. I’ve no dependants. I’m ready for immediate consumption.” Despite its period setting, it shows – in details from a man obsessively checking the news for updates, to evergreen comic asides (“Always go to a taxi driver when you want a sane, independent opinion”) – that fiction which lasts does so not because it shows how much times have changed, but how much people have remained the same.