The book that changed Britain: why the Lady Chatterley’s Lover trial still matters 60 years later

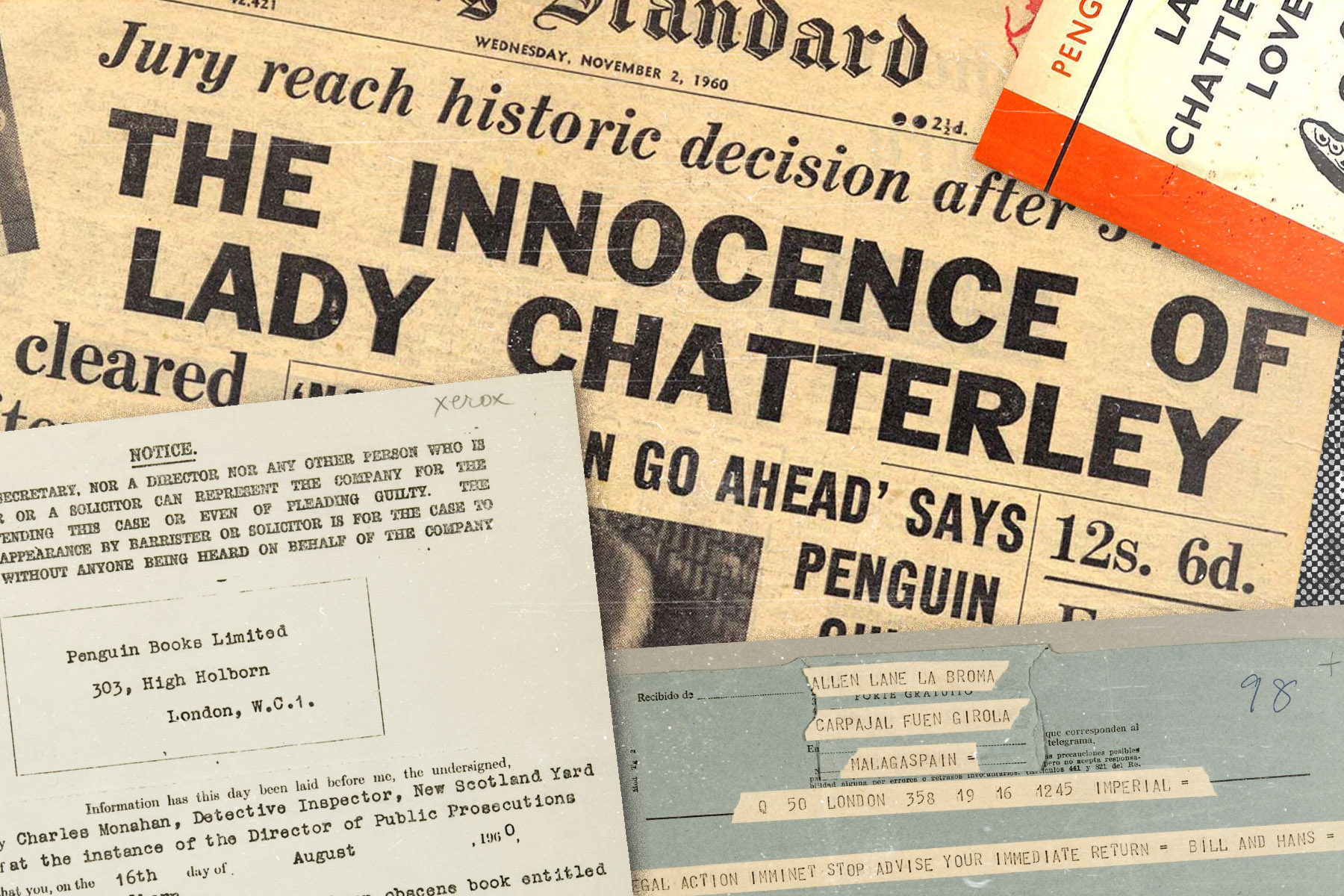

In August 1960 Sir Allen Lane, founder of Penguin Books, was in Spain when he received an urgent telegram from his colleagues. “LEGAL ACTION IMMINENT STOP ADVISE YOUR IMMEDIATE RETURN.” The legal action was a criminal prosecution for the planned publication of Penguin Book no. 1484, better known as Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D. H. Lawrence. The trial began 60 years ago today, on 20 October 1960, and barrister Geoffrey Robertson QC says “no other jury verdict in British history has had such a deep social impact”. It resonates with us still.

This groundbreaking case was the first prosecution of a work of literary merit under the Obscene Publications Act 1959, and the publication of Lady Chatterley’s Lover was a provocation by Penguin to test the new law, 30 years after Lawrence’s death. Not that the authorities needed much provocation: the Director of Public Prosecutions and police had pursued a vendetta against Lawrence’s work for decades, burning his 1915 novel The Rainbow; intercepting his post to seize his poems Pansies; and raiding an exhibition of his paintings.

The establishment was itching for another battle over Lawrence, and Lady Chatterley was the perfect conduit. The novel was, Lawrence said, part of his “labour [to] make the sex relations valid and precious, instead of shameful.” It was “the furthest I have gone.” The novel is about Lady Constance Chatterley, who, finding herself starved of physical love after her husband is paralysed in the war, turns to her gamekeeper, Mellors, to satisfy her sexual appetite. There are a dozen explicit sex scenes in their story – the prosecution at the trial read out to the jury the number of times each “good old Anglo-Saxon four-letter word” was used – but the sex is the measure of how Connie and Mellors build their relationship, and shows a respect toward the physical – not shame or disgust.

The defence diligently defended Lawrence’s reputation: comparing his book stylistically to the Bible; arguing for the “puritanical” quality of a description of “the weight of a man’s balls”

The trial itself is notorious for the words used by prosecutor Mervyn Griffith-Jones QC to the jury: “Is it a book you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?” This line, which got an unintended laugh, is typically seen as a rich man’s out-of-touch viewpoint, but it’s more than that. As defence barrister Gerald Gardiner put it, “that whole attitude is one which Penguin Books was formed to fight against… the attitude that it is all right to publish a special edition at five or ten guineas so that people who are less well off cannot read what other people read.” Allen Lane had formed Penguin Books because “he thought it would be a good thing if the ordinary people were able to afford to buy good books”, and the trial was an extension of Penguin’s role as a driver of social change and progress.

During the trial, the experts called by the defence diligently defended Lawrence’s reputation: comparing his book stylistically to the Bible; arguing for the “puritanical” quality of a description of “the weight of a man’s balls”; and the Bishop of Woolwich, who was rebuked by the Archbishop of Canterbury afterwards, made the headline-grabbing statement that it was a book all Christians should read.

Game to the end, the prosecution appealed to the jury – this populism echoes today – not to trust “the so-called experts” who had given evidence, but to apply “common sense” instead, via an insidious mistrust of the working classes: “Is that how the girls working in the factory are going to read this book?” Even the judge, Mr Justice Byrne, in his summing-up, tilted in this snobbish direction, saying the low price of the book meant it would “be available for all and sundry to read. ...You have to think of people with no literary background, with little or no learning.”

Lawrence’s stepdaughter said, “I feel as if a window has been opened and a fresh air has blown right through England”

But it was a doomed enterprise. It took just three hours for the jury to unanimously find Penguin Books not guilty of an obscene publication. The judge, contrary to tradition, did not thank the jury afterwards.

The verdict was out, the dam broken, and Penguin managed to get some copies on sale the same day, with two million copies sold nationwide a month later. (The printers who’d refused to work on the book had a change of heart and helped with urgent reprints.) Newspapers including The Times and Daily Telegraph were outraged by the verdict, and Tory MPs called for The Guardian to be prosecuted for printing one of the four-letter words used during the trial.

But they were leaves in the wind of change. The sales spoke for themselves, and Lawrence’s stepdaughter Barbara Barr said, “I feel as if a window has been opened and a fresh air has blown right through England.” Was Geoffrey Robertson QC right about the impact of the trial? In a narrow sense, yes: the law had been defanged and it was now impossible to prosecute a work of literary merit for obscenity: the DPP didn’t bother to try with Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer or William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, and the last gasp of an initial conviction for Hubert Selby Jr’s Last Exit to Brooklyn was overturned on appeal.

The Chatterley trial expanded Britain’s vision of the future, right at the beginning of the liberalising decade of the 1960s

In a broader sense, too, the Chatterley trial expanded Britain’s vision of the future, right at the beginning of the liberalising decade of the 1960s. The verdict was almost certainly a factor in the abolition of the Lord Chamberlain’s role as theatre censor in 1968 and the rise of gritty, explicit working-class drama on television. Whether it is directly linked to the liberalisation of laws on divorce, homosexuality and abortion in the same decade is doubtful, but they are all part of the same change in the social contract. As Philip Larkin put it memorably in ‘Annus Mirabilis’:

Sexual intercourse began

In nineteen sixty-three

(which was rather late for me) –

Between the end of the Chatterley ban

And the Beatles’ first LP.

Perhaps the best symbol of how the Lady Chatterley’s Lover trial continues to embody the change it brought about is that last year, the copy of the book annotated by Mr Justice Byrne was sold for more than £50,000 to an overseas bidder. Immediately, the UK’s arts minister put a hold on the book leaving the UK so a crowdfunding effort could take place to keep this “important part of our nation’s history” in the country. As a result, the judge’s copy was acquired by Bristol University, and a book which began as a scourge of the establishment had become, in the end, a totem of national pride.

What did you think of this article? Let us know at editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk.

Image: Ryan MacEachern/Penguin