Olivia Manning: literature’s brilliant, overlooked woman of war

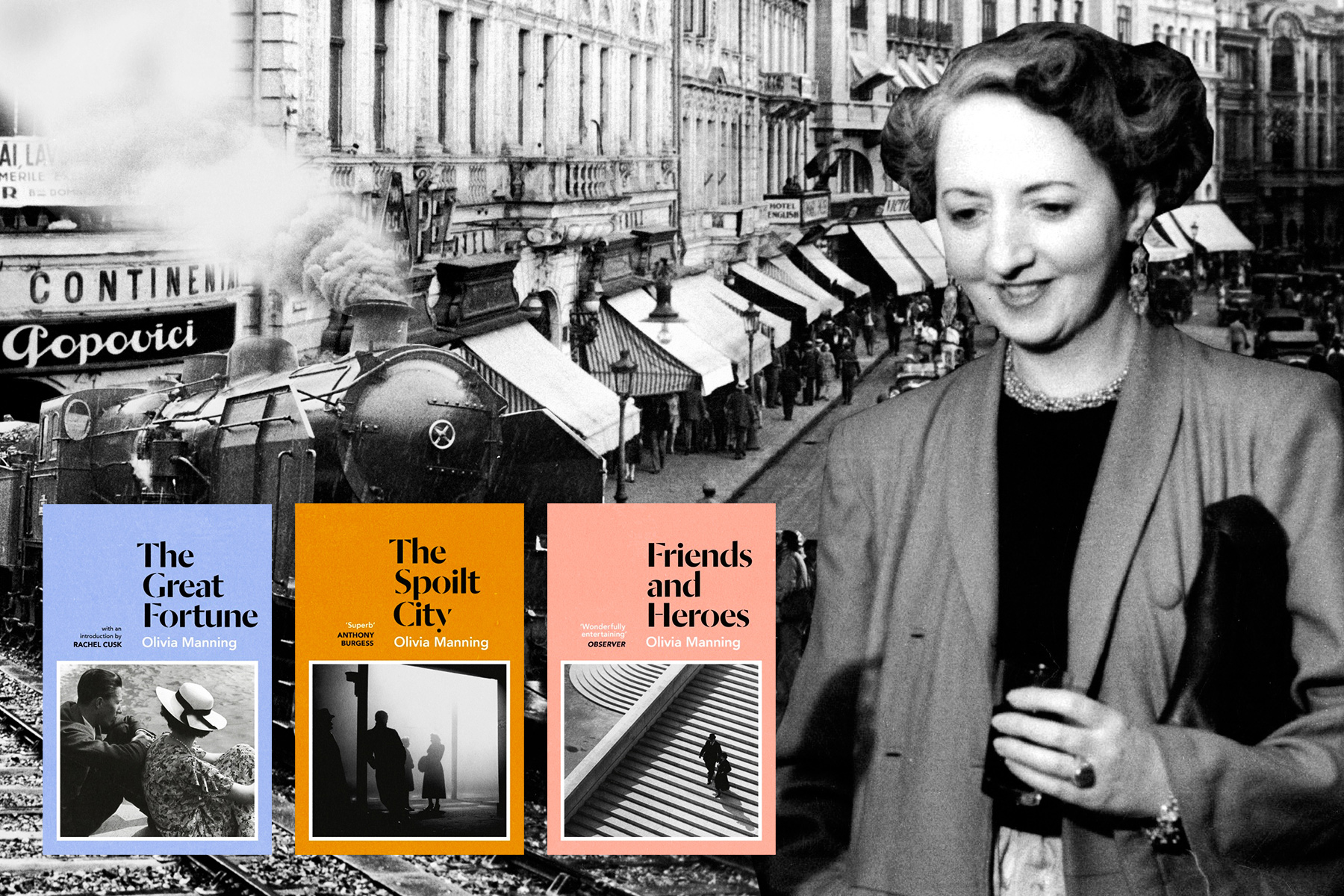

Her life was stranger than the extraordinary fiction inspired by it. As her Balkan Trilogy is reissued, Alice Vincent asks why it took so long for Olivia Manning's talent to be appreciated?

Who could have imagined that, in the grim middle of February 2021, a trip to Bucharest on the cusp of the Second World War would be so welcome.

This is less of a testament to the tedium of the pandemic than it is Olivia Manning’s writing. Manning wrote some two dozen novels between her early twenties and death, in 1980, and yet remains something of a literary footnote. A correspondent and writer whose own life was extraordinary (doomed love affairs; a spy for a husband; international wartime adventure; a complicated lifelong relationship with Stevie Smith; a fierce rivalry with Iris Murdoch), Manning’s talent was equalled by her quiet fury that she wasn’t better read in her time. Now, some 40 years after her death, she’s finally due a resurgence.

It was The Balkan Trilogy that first swept me into Manningland. Consisting of The Great Fortune (1960), The Spoilt City (1962) and Friends and Heroes (1965), the 900-odd page saga is nevertheless a transportive one. The premise is simple: We meet 21-year-old Harriet Pringle and her new husband Guy on the train to Bucharest, shortly after they’ve passed through Venice. He is an English lecturer at the University of Bucharest; they have been married a matter of weeks after a summer romance in London. The whole of Europe holds its breath for war.

As the three novels unfold, Manning’s trilogy manages an artful balance between stasis – of the fine restaurants and hotel bars in which they dine, along with the rest of the British ex-pat community in supposedly politically neutral Romania – and action, as the couple attempt to outrun the grasp of the Nazi occupation: first to Athens, then Palestine, Cairo and, finally to Damascus. Historical events such as the evacuation of Dunkirk and the Italian alliance with Germany pepper the slowly boiling soup that surrounds Manning’s immaculately drawn cast of characters. As Rachel Cusk, who introduces the series, writes: “they have the feeling of real beings who happen to find themselves caught in the narrative frame.”

'Depending on your inclination, The Great Fortune is either a trilogy about a marriage or one about the Nazis'

Among them, the infuriatingly generous Guy, who offers support to everyone bar his wife; the supercilious, hopelessly romantic Harriet, who picks up the pieces; Sophie Oresanu, a Romanian student who wants Guy to marry her for visa reasons; Clarence Lawson, unrelentingly in unrequited love with Harriet and Prince Yakimov, literature’s most deliciously outrageous scrounger. It is the dance between these – against the sweltering summers and relentless winters of Bucharest at the end of the 1930s – that Manning choreographs so well. Depending on your reading and inclination, The Great Fortune is either a trilogy about a marriage or one about the Nazis.

“These are still books we can enjoy today,” says Laurie Ip Fung Chun, the editor at Windmill responsible for re-issuing the trilogy with a 2020 audience in mind. “I think people might assume that Manning’s books might be too of their time, but they are about the big changes in someone’s life.”

And Manning would know them, too. Harriet’s story was hewn from her own. Harriet is a woman who claims not to have any parents, who was raised instead by an aunt who “used to say, ‘No wonder your mummy and daddy don’t love you’” and who winds up falling for effervescent dreamer Guy. Manning, meanwhile, was punished by her mother for reading literary journals and made a mission of escaping her Portsmouth hometown for the glamour of literary London. As her biographer Deirdre David notes: “No one advised her, few encouraged her, yet after typing all day in a solicitor’s office, she managed to write an enormously long novel [and] made it her business to discover the name of Joyce’s Paris publisher.”

'Everything she had to say about her life was extraordinary.'

Romantically, Manning's made Harriet’s life look tame. The author married swiftly (the ceremony was witnessed by Stevie Smith and fellow poet Louis MacNeice) and moved to Bucharest with her new husband, Reggie Smith – who was later ousted as a Communist spy by MI5. The couple roamed around Europe during the war, not unlike the Pringles. That scene from Friends and Heroes where Harriet baptised Guy with a cup of tea so as to avoid spending the afterlife apart? Manning did it first.

“She felt the most valuable fiction was that which drew upon the author's life and experience, but also history itself,” says Deirdre David, who wrote the author’s biography, Olivia Manning: A Woman at War. “That if somehow you could mesh together the life, and the historical moment in which the life is lived, then that could produce good fiction.”

David began to explore Manning’s story having read The Balkan Trilogy. Ploughing deeper into her earlier work (little of which remains in print), David “just became very interested in her, as a writer - and everything she had to say about her life was extraordinary.”

Manning returned to London – having “barely made it into the Middle East”, according to David – in 1945 and took a job with the BBC. She released books throughout the late Forties, but it would be another 15 years before The Great Fortune would come out. It didn’t receive the accolades Manning hoped for; something that pockmarked her entire career. While she mixed in literary circles, Manning never received the recognition of her more lauded friends – and she wasn’t gracious about it, either. “I don’t want fame when I’m dead,” she said, “I want it now.”

“She felt that people like Iris Murdoch, who she called the Glamour Girl of the Sunday Times got too much attention,” says David. “And she hated Elizabeth Bowen and she made no secret of this. [Manning] felt herself, you know, always to the perennial outsider.”

But bad manners don’t warrant bad reviews – plus Manning’s writing was genuinely very good, if lacking the Sixties experimentalism that made Murdoch such a star. Why, I ask David, was she so overlooked for so long? She replies that it’s easier to explain by what Manning wasn’t: “You know, she was not Virginia Woolf. She was not Kingsley Amis. She was not Iris Murdoch. She was not an intellectual novelist. What was she was, was unique.”

It is sad – and ironic – that Manning’s work did achieve recognition after her death, just as some of her friends said it would. In 1987, both The Balkan Trilogy and The Levant Trilogy were adapted for television as The Fortunes of War, starring then-sweethearts Kenneth Branagh and Emma Thompson.

In the 40 years that have passed since The Great Fortune – and the five novels that followed – contemporary audiences have also managed to see Manning’s books away from the context of the war. The stories may be set against a backdrop of international conflict, says Ip Fung Chun, but they’re also of Harriet “finding herself, finding the woman she wants to be. She starts off being very naïve at the beginning, and almost slightly romanticising the situation. But she definitely comes into her own.” Decades on, these are still narratives that need to be told – and when they’re as entertainingly done as The Balkan Trilogy, there’s no excuse not to read them.