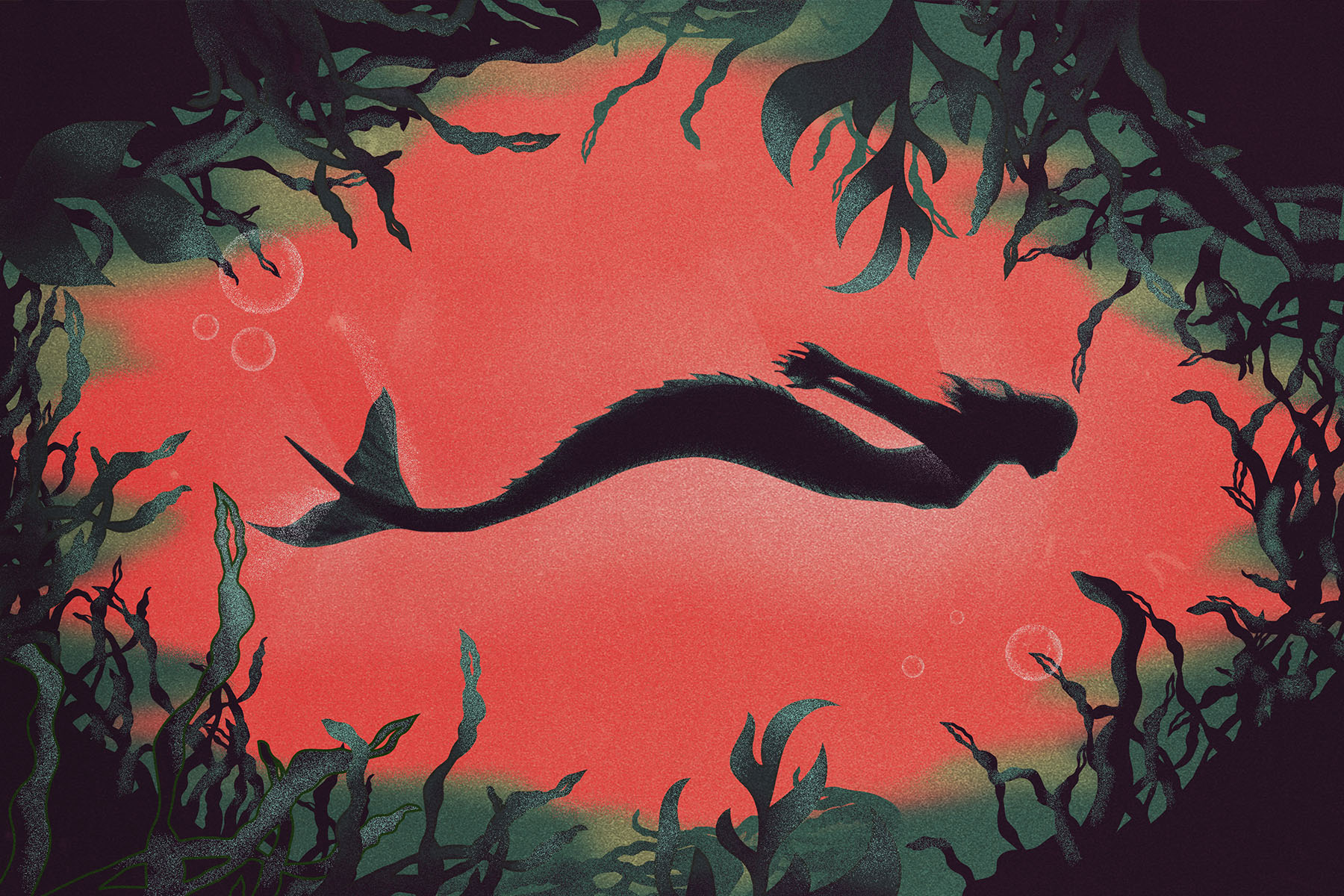

Siren call: How fiction reclaimed the mermaid’s tale

After centuries of entrapment, the mermaid is finally getting to tell her own story. From Monique Roffey to Rivers Solomon, contemporary writers are offering new, feminist retellings of a favourite fable.

Her call has echoed through the centuries and across cultures; she takes many forms: from an Assyrian goddess to the nightmarish Japanese Ningyo, the mermaid has long captured our imaginations. But a wave of recent mermaid-based books suggests that these mythical creatures still have resonance among readers today. Clearly, there is something about mermaids that we can’t resist.

Publishing is currently under the spell of stories inspired by wicked women. Female authors such as Helen Oyeyemi, Francine Pine and Evie Wyld have re-written a new kind of feminist horror that reflects a modern womanhood. The witch, in particular, has become synonymous with female empowerment, though she often pays a heavy price for it. But what about the mermaid? What does her presence on our pages suggest about the world we live in – and how has her modern treatment changed the way we see her?

For centuries, the tail has been tragic. Perhaps the most famous mermaid story in the western world is Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, published in 1837. Andersen’s original fairy tale is far darker than the plucky redhead Disney presented us with. His heroine undergoes a brutal exchange for life on land: each step she takes is akin to “walking on knives”. She cannot speak because her tongue is cut out. Why go through all this? Well, according to the Danish writer, mermaids live for hundreds of years but dissolve into sea-foam at the end of it all. The mermaid’s chances of a soul hinge on the prince’s marrying her. Only, he doesn’t; he treats like a pet. The Little Mermaid is rife with purgatory and pain: ultimately, she is left to circle the earth as a kind of air spirit, as ephemeral and trapped as the sea-bound creature we first meet.

'The mermaid is a curious sex symbol, given that she is half-fish, but this is part of what reels her male victims in'

There are often many versions of a single story and folklore is particularly difficult to date, but Imogen Hermes Gowar mixes history into her compelling debut, The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock (2018). Set in 18th-century England, the novel follows merchant Jonah Hancock, who finds that his ship has been exchanged for what looks like a dead mermaid. This sweeps him up in a whirlwind of fame and fortune, but is this a real mermaid or a clever hoax? There’s definitely something fishy going on here. Published in the same year, Kirsty Logan’s The Gloaming also dangles the question of artifice. Professional mermaid Pearl might perform water trickery in travelling shows, or she might be something else. But where Pearl is all honey, salt and guile, Gowar’s mermaid is “wizened”, “its mouth open in an eternal, ape-like scream”. Aycayia, too, stirs revulsion as well as desire.

The mermaid is a curious sex symbol, given that she is half-fish, but this is part of what reels her male victims in. They can only gaze upon her beauty and otherness. It’s a classic tale of thwarted lust. That tale, however, is being twisted.

In The Pisces by Melissa Broder (2018), we meet a merman: “the tail starts below all that”. In this firmly millennial novel, PhD student Lucy is staying in Venice Beach, attending therapy for her love addiction. When she encounters Theo, fluids leak on every page. In the (explicit) sex scenes, gender perceptions are fluid, too, as Broder flips the binary: “I was yang or yin, or whichever the male was, and he was female for a moment.” Lucy enjoys earth-shattering orgasms as a result. When she asks her lover if he is real, he laughs: “I suffer like I’m real.” While modern daters might recognise some of the merman’s more dubious tactics to hook his prey, Lucy’s approach to relationships can hardly be called healthy. Doomed love and dodgy promises? The merfolk are at it again.

But not all modern mermaids are so macabre. In The Deep by Rivers Solomon, the descendants of enslaved African women thrown from ships can breathe underwater and have formed a paradisical society. Everyone lives in blissful forgetfulness, except Yetu, who carries the trauma of the past and, in an effort to escape it, swims to the surface. The Deep is a story that lends magic to the murky waters of history, published in 2019. The following year, various authors including Emma Glass and Irenosen Okojie, contributed to the anthology Hag: Forgotten Folktales Retold, offering their own takes on some of the more obscure folklore of Britain and Ireland. There are selkies and endless rain and yes, there is a mermaid.

In the Cornish legend, The Mermaid and the Man of Cury, a mermaid named Morvena gives her golden comb to a local man, promising him three wishes. But he struggles to escape her clutches and she curses him to a watery death nine years hence. Hag contains Natasha Carthew’s version, The Droll of the Mermaid, in which it is the man’s descendant, Lowan, who breaks the family curse with an act of compassion. Morvena is still dangerous, but she has gained a sense of justice.

It seems that writers are drifting towards a new maid of the sea. We can see it in films such as The Shape of Water (2017) and in the mermaid’s association with LGBTQ+ groups. She is no longer just a sweet-voiced seductress; she can be a he; she can be ungendered; she can speak her mind as well as sing and she has things to say. Maybe, as Roffey points out, the myth fascinates us so much because water makes up a large percentage of our own bodies: “More than any other element. We may think of ourselves as earthlings,” she says, “but we are waterlings.” Perhaps we’re not so dissimilar after all.

What did you think of this article? Email editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk and let us know.

Image: Ryan MacEachern / Penguin