- Home |

- Search Results |

- Sara Taylor on multi-threaded narratives

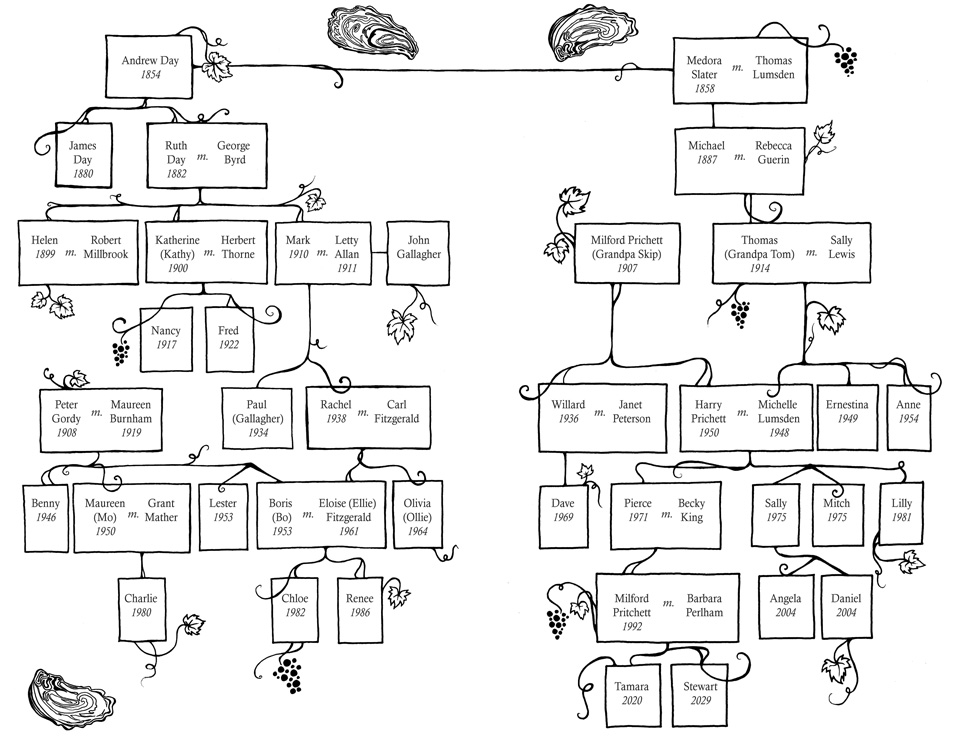

One kind of novel: someone – let’s call them Noel – tells a story from the first thing that happened to the last thing that happened. Another kind of novel: Noel still tells his story, but his brother and daughter and ex-lover and grandmother and postman all get to tell their stories as well, and because we’re all the heroes of our own stories Noel might only get a walk-on part in most of these.

A strength of the first way is that it’s comfortable, familiar, the way that humans have told stories for hundreds of years. A strength of the second way is that it has the chance to get closer to the way things are; we live stories that are complicated and confused, and the characters around us all have knowledge and experience that we lack.

If you wanted to write a novel with many threads, you could begin by asking questions: who are the characters? How do they interact? What does one character’s story tell the reader about the characters that don’t appear? What does one know that another doesn’t? Who’s lying, and who’s lying to themselves? Then you could map it out, plan which characters tell what parts of the story, when information comes to light, what parts of their stories to show and what parts to gloss past. Then all you would need to do is to follow your plan.

My socks never match and my kitchen is frightening, so I tend to take a different approach. First I set the limits: a small place, over a few hundred years. Then I write Noel’s story: a moment when something happens, when something changes for him. When it’s finished I look at it and try to find the important people. They could be his parents, a friend he no longer speaks to, a child he doesn’t know he has, the person walking down the sidewalk that he only notices for a moment before he crashes his car and then forgets about them forever.

I write their stories – some I keep and some get thrown away – and look again for the important people. After repeating the process a few times the pattern of how the characters all connect emerges, and it becomes easy to see where important stories are missing, and to see which ones need to be cut out.

Either way, the result should be the same: a novel in the shape of a web, a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts, a shard of mirror held up to reality in such a way that, for a moment, a small part of it makes sense.