- Home |

- Search Results |

- The Rise and Fall of Nations by Ruchir Sharma

The Rise and Fall of Nations by Ruchir Sharma

In his pioneering work, Ruchir Sharma spells out ten clear rules for identifying the next big winners and losers in the global economy. Here he outlines his approach to monitoring trends in inequality through tracking the wealth of 'bad billionaires'

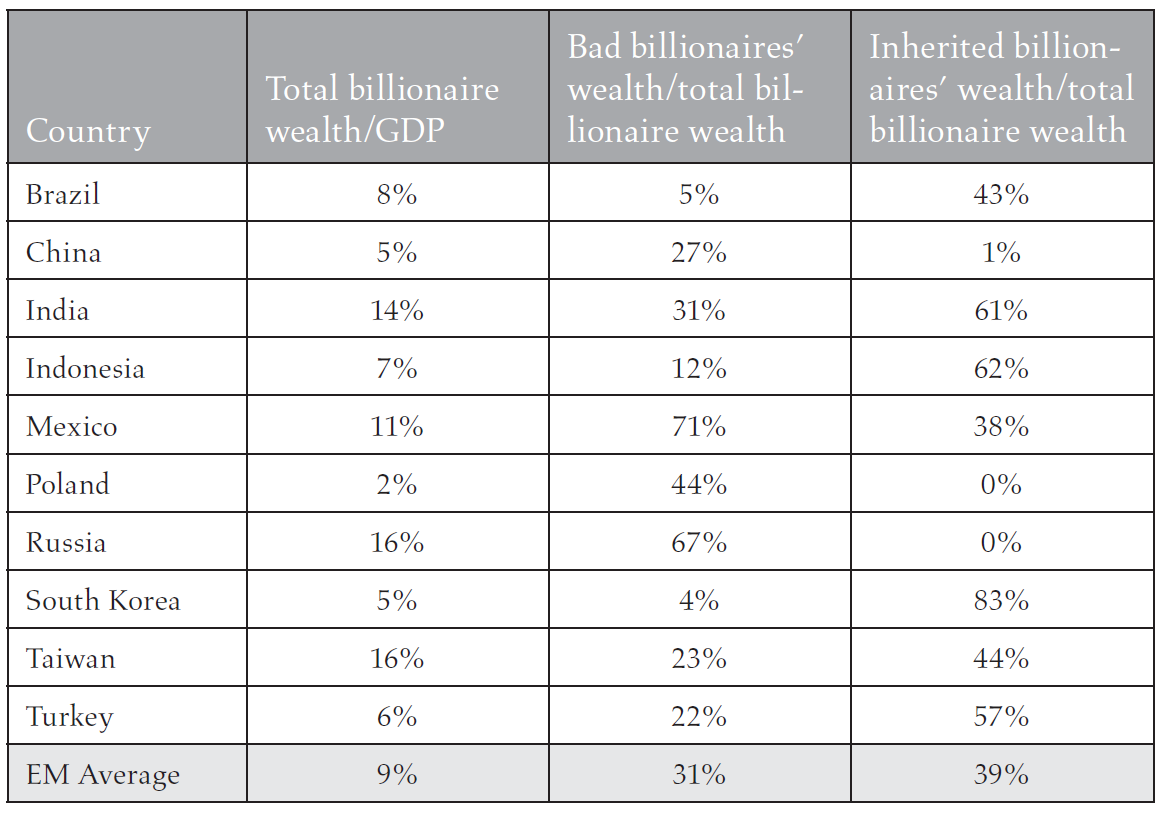

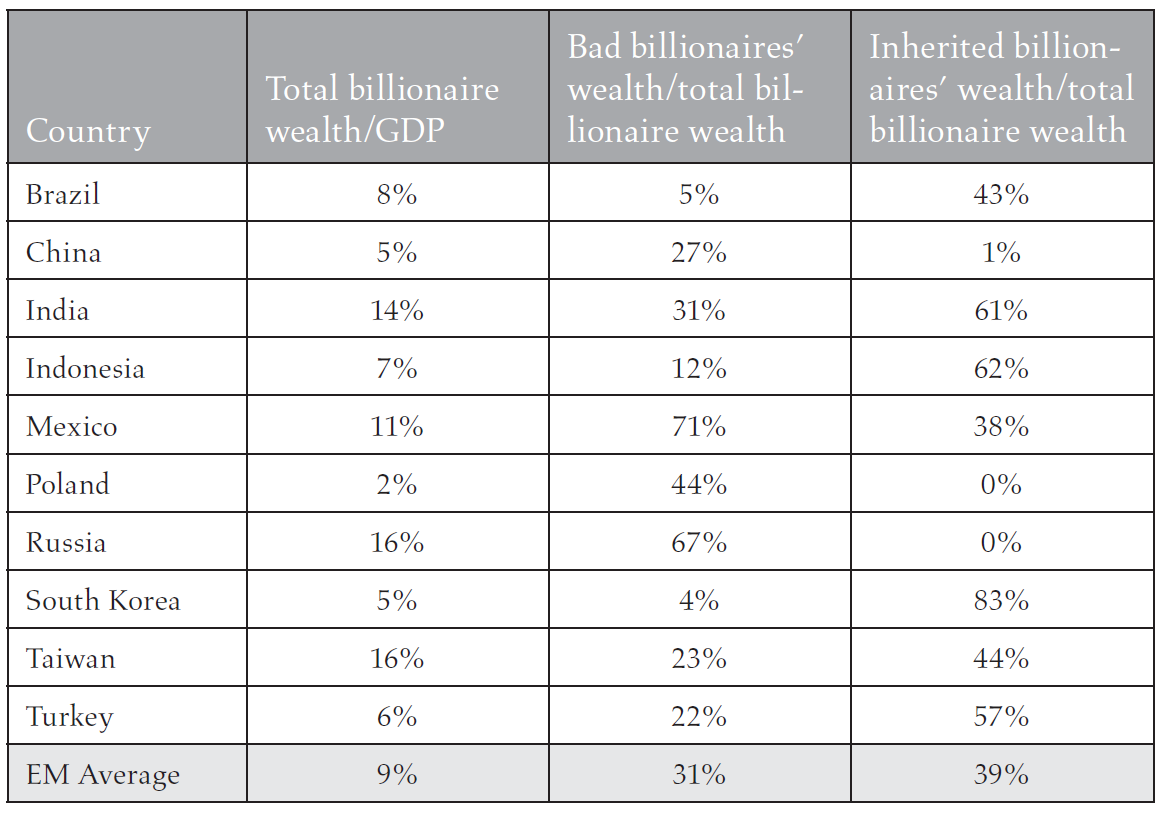

To sceptics who find issues like wealth inequality or an approach like reading billionaire lists too soft to take seriously, I would argue that this is an increasingly vital sign. Some world leaders still tend to dismiss vices like inequality, and the corruption that often feeds it, as timeless and inevitable sins that are common to all countries, particularly poor ones in the chaotic early stages of development. But this is a cop-out. Developing societies do tend to be more unequal than rich ones, but it is increasingly unclear that their inequality problem will naturally disappear.

The belief that inequality fades over time had been the working assumption since the 1950s, when the economist Simon Kuznets pointed out that countries tend to grow more unequal in the early stages of development, as some poor farmers move to better-paying factory jobs in the cities, and less unequal in the later stages, as the urban middle class grows. Today, however, inequality appears to be rising at all stages of development: in poor, middle-class, and rich countries. One reason for the widening threat of inequality is that the period of intense globalization before 2008 tended to depress blue-collar wages. It became much easier to shift factory jobs to low-wage countries, while continuing advances in technology and automation was replacing jobs that had earlier lifted many people into the middle class. As inequality spreads within countries, at every level of development, it is increasingly important to monitor the wealth gaps in all countries, all the time.