- Home |

- Search Results |

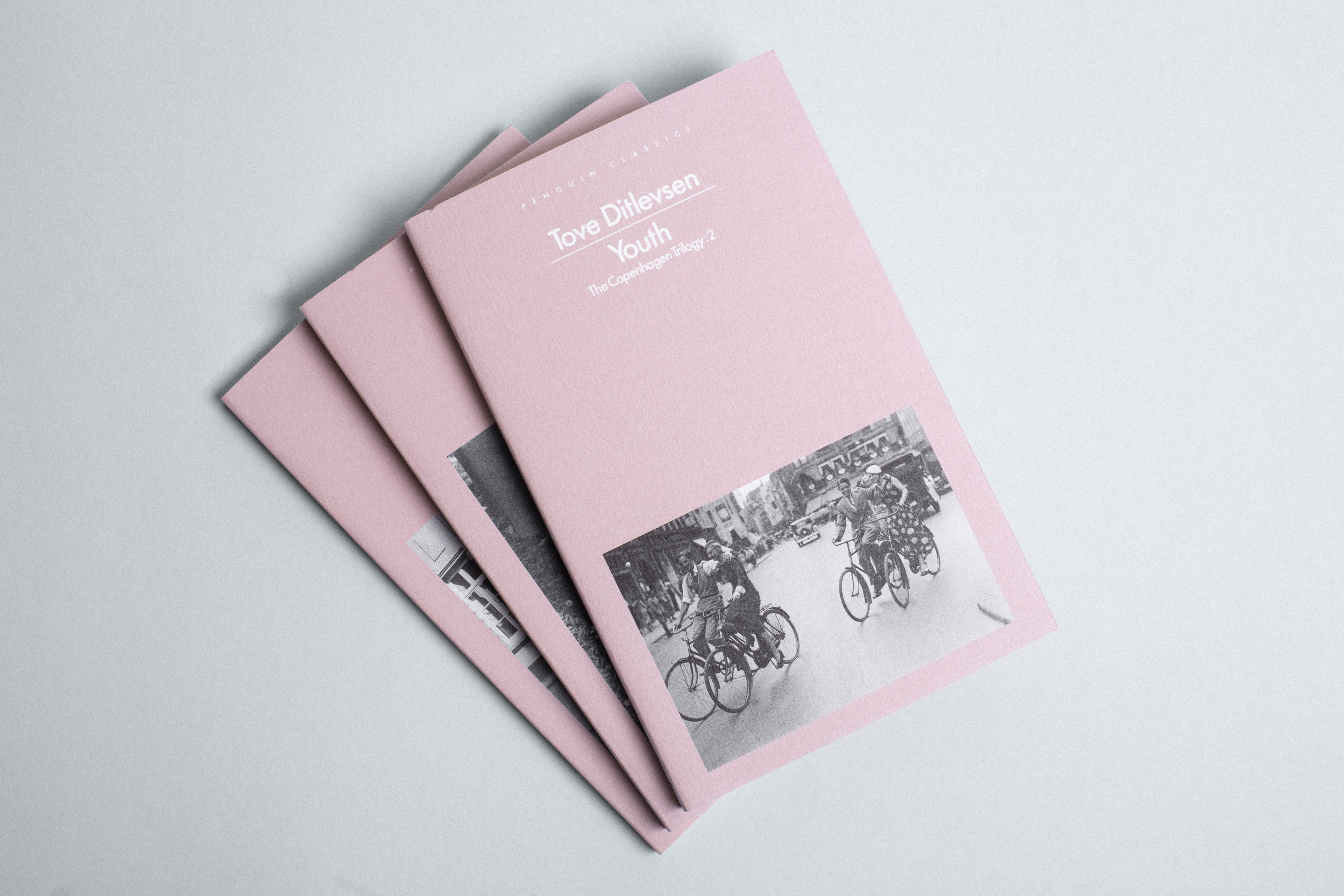

- ‘The Copenhagen Trilogy is a testament of survival’: Erica Wagner on Tove Ditlevsen

‘The Copenhagen Trilogy is a testament of survival’: Erica Wagner on Tove Ditlevsen

Initially dismissed for being working-class and female, Ditlevsen is enjoying a renaissance with 'Tove fever' sweeping Denmark. Author and critic Erica Wagner details why her Copenhagen Trilogy is as pertinent as when it was first published in the 60s.

These days Vesterbro – the neighbourhood just west of Copenhagen’s Central Station – is a place of bars, coffee shops and tattoo parlours. As in downtown Manhattan, it was once home to the city’s meatpacking district and similarly the local butcher’s shops have now been transformed into fashionable restaurants. But it is the older, down-at-heel Vesterbro that is vividly conjured in the first volume of Tove Ditlevsen’s remarkable Copenhagen Trilogy: a place of poverty, of shadows, of hunger. ‘Childhood is long and narrow like a coffin,’ Ditlevsen writes, ‘and you can’t get out of it on your own.’, she states in Childhood, the first in the trilogy. Yet despite the darkness that haunts these three books, they shine with Ditlevsen’s honesty and humanity.

Ditlevsen, who was born in 1917 and died by suicide in 1976, is one of Denmark’s most highly-regarded writers; these books, translated by Tiina Nunnally and Michael Favala Goldman, offer a striking introduction to her life and her work. This is ruthlessly unsentimental autobiographical writing: Ditlevsen, in charting her difficult path to adulthood and her growth as an artist, lays herself bare: her pitiless gaze is brutally exhilarating.

Hers is not the conventional life of a writer. At the outset of Childhood her father (‘big and black and old like the stove’) is working as a stoker; disaster strikes when he loses his job. There is a ‘no-man’s-land’ between her and her mother; her older brother Edvin is a distant presence, hovering at the edges of all these books. But despite her difficult circumstances, Tove begins to find her vocation as a writer – not least thanks to a kindly librarian, an experience many readers will recognize. Writing poetry becomes her consolation in ‘this uncertain, trembling world’ and it is her art that leads her out into her adult life.

'We are absolutely present in her pain and loss of control.'

But that path is fraught with difficulty, and the shadow of war hangs over her story. As the second volume, Youth, opens, she begins her independent life: the day she starts a new job in a typing pool is the day that Hitler invades Austria, she writers matter-of-factly. But the focus here is not on global politics; it is the inner drive of the writer. One evening her landlady invites her to drink a toast to the Führer but she is more intent on her mail – she’s sent her poems to the editor of a journal called Wild Wheat. With astonished pride she records his response: ‘Dear Tove Ditlevsen: Two of your poems are, to put it mildly, not good, but the third, ‘To My Dead Child’, I can use. Sincerely, Viggo F. Møller.’

Viggo F., as she calls him, is decades older than she is, but he becomes her first husband, the first in a line of unsatisfying, damaging relationship that will eventually pull her into the cycle of addiction that led to her early death. In clear and tender prose, Ditlevsen conjures an extraordinary mixture of hope and fear at the end of Youth: hope for her writing, her career, fear that she herself is not adequate, is not enough. In the central volume’s final pages, she comes home to find her first book of poems – Pigesind, which means ‘Girl’s mind’ – fresh from the publisher. She feels ‘a solemn happiness’. ‘The book will always exist, regardless of how my fate takes shape,’ she writes. But at the same time she tries to hide what she calls her ‘ordinary’ self from Viggo F.: ‘he isn’t the least bit interested in ordinary people… I hide everything that could make him have misgivings about marrying me.’

It is her own self-doubt that shadows the final volume, Dependency. It’s worth noting that its initial title, upon its publication in 1971, was Gift – Danish for ‘married’. Dependency much more accurately conveys the way in which Ditvelsen not only moves from man to man, but into the numbing fog of drugs that will sap her vitality and her talent. It is Carl, her third husband, who introduces her to Demerol; when he first gives her an injection ‘a bliss I have never felt before spreads through my entire body. The room expands to a radiant hall, and I feel completely relaxed, lazy and happy as never before.’ The reader feels as helpless as the author as the cottony drug-fog envelops her: we are absolutely present in her pain and loss of control.

'Writing poetry becomes her consolation'

The best autobiography enables us to enter another consciousness seamlessly. This is precisely what Ditlevsen achieves in this sequence of books. When her first book is published, she writes that the achievement is a ‘miracle’ to her; and indeed her work, seemingly so simple, has the miraculous quality of a life perceived in perfect clarity. Despite the author’s untimely death, The Copenhagen Trilogy is a powerful – and uplifting – testament of survival.