In defence of the exclamation mark!

Are you suffering from a case of bangorrhea? For a diagnosis, turn to your sent emails, Whatsapp or Twitter feed, and count the exclamation marks dispatched in the past few days. Any more than a couple and chances are you’re infected – don’t worry, everybody else is, too.

The internet age has rather transformed the exclamation mark, elevating it from the page to something of a personality. We sign off emails with “no worries if not!”, reply to text messages containing fairly banal life updates with “omg!!” Donald Trump, famed bangorrheac, has long been mocked for for his plentiful exclamation mark usage (“SAD!”). And yet, children and budding writers are still being taught to use them sparingly. Perhaps it’s time literature recognised the internet’s favourite sentence-ender.

Because we love exclamation marks far more than we like to admit. Long considered the “fun uncle” of the punctuation family, they’ve been sneered at, overlooked and trivialised in literature for centuries. Elmore Leonard famously decreed: “You are allowed no more than two or three [exclamation marks] per 100,000 words of prose,” before proceeding to use 16 times that allowance in his own work. In red pen, F Scott Fitzgerald scribbled “Cut out all these exclamation points. An exclamation point is like laughing at your own joke” on a Sheilah Graham play. Nevertheless, you will find 356 of them across his four novels.

Anton Chekov wrote an entire short story in their honour called 'The Exclamation Mark'

Our jaunty friends have been sneaking into the canon for years. Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, Jane Austen and Toni Morrison – serious writers all – knew the strength and power of an exclamation mark. So why such denial?

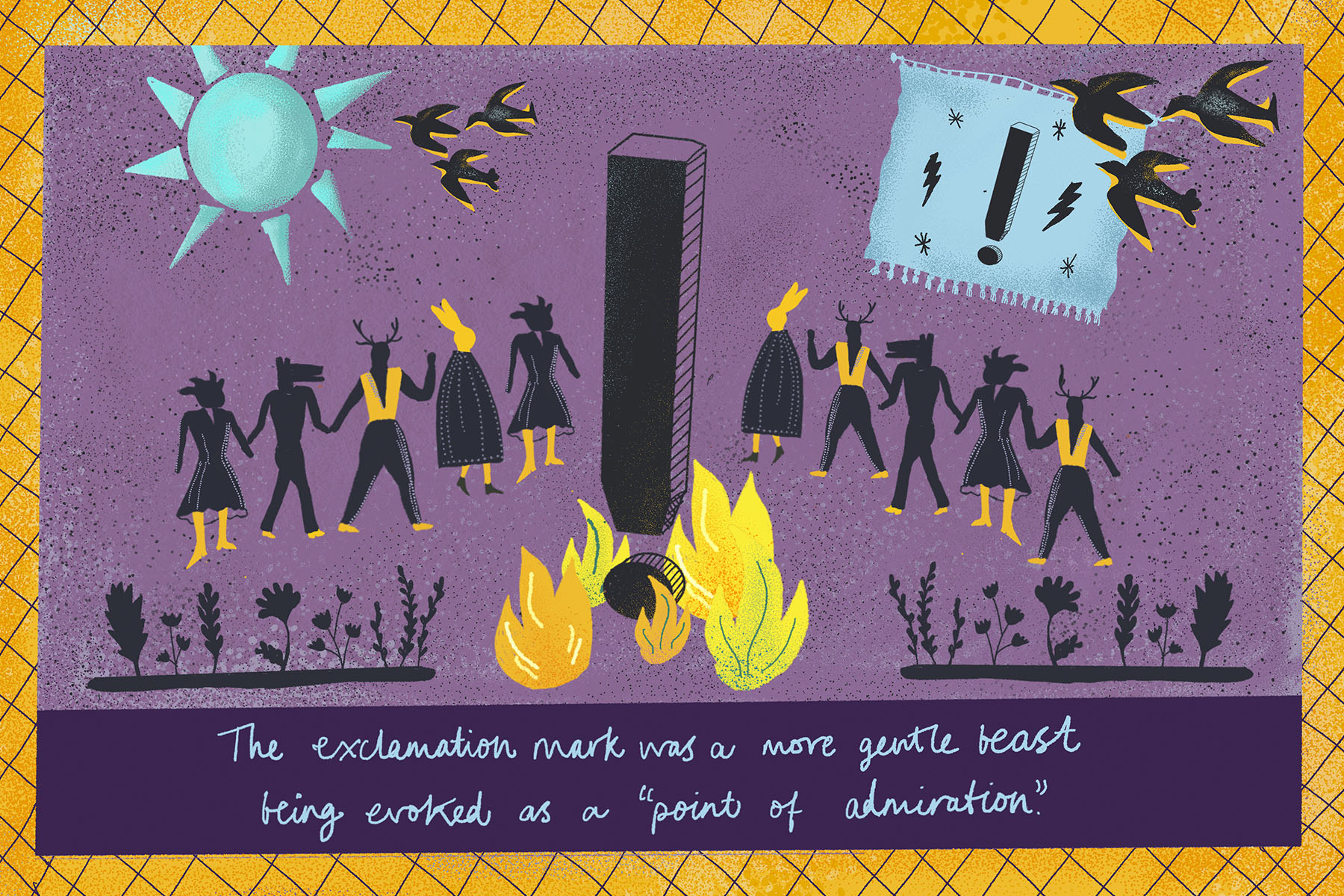

It wasn’t always thus: the mark wasn’t one of “exclamation” until Samuel Johnson said so, in the 18th century. Before then, the exclamation mark was a more gentle beast, being evoked as a “point of admiration” (“I love your hat!”) in the 14th century. By the 17th the mark was referred to as “the wonderer” (“Oh, what a magnificent hatstand!”). The Victorians had no shame, with Anton Chekov even writing an entire short story in their honour – called 'The Exclamation Mark', its protagonist was an uptight civil servant who didn’t use one for 40 years (what a dull little life!).

The turn of the 20th century saw an inevitable backlash to such jollity, with the exception of the modernists, who adored them (see Woolf, who liberally scattered her stream-of-consciousness prose with them). The typewriter further knobbled the exclamation mark’s cause – although the machine was invented in the 19th century, a dedicated exclamation mark key wasn’t added until 1970 (!) as the mark wasn’t deemed necessary in professional writing. Dedicated enthusiasts had to make do by typing a full stop, then backspacing and placing a comma above it.

'The single exclamation mark is being used not as an intensity marker, but as a sincerity marker'

As a child of the Nineties, I too was taught that exclamation marks were bad. Indeed, I rarely use them in my writing. Nevertheless, I probably drop about 50 a day – in emails, text messages, social media and the other relentless written communication the internet demands.

There’s a meme that’s been doing the rounds recently, in which a millennial looks downcast and paranoid when their boss replies to something saying “thanks.” Why? Because, as author Gretchen McCulloch has pointed out, in an era of so much non-verbal communication, “The single exclamation mark is being used not as an intensity marker, but as a sincerity marker.” Typing “great job.” looks underwhelmed at best, sarcastic at worst. But “great job!” ? That’s enough to make someone’s day.

Where sincerity starts, irony soon follows, and so it has proved online. Exclamation marks have become part of a social-media specific dialect to prompt humour and irreverence. Digitally literate millennials deploy them for self-deprecating wit (“I contain multitudes!”). In doing so, they rather prove Fitzgerald right – an exclamation mark is like laughing at your own joke. That’s why we love it.

But back to the books. Our reluctance to send exclamation mark-free emails for fear of seeming too formal, grumpy or cross was rather predicted by Ian McEwan in Atonement (2001), in which Robbie Turner inserts exclamation marks into his letter to Cecilia Tallis because it seems too stuffy without them. More recently, in 2015, Julian Barnes admitted that he felt sorry for the exclamation mark, which had fallen from “high company” to becoming “the slag of punctuation, slumming around with emoticons and OMGs.”

But then a year later along came Ali Smith’s Seasonal, a quartet of books written in the wake of the EU Referendum in which the author often places an exclamation mark singly in its own paragraph to express revelation or delight. In doing so, she inspires it in the reader. In her essays, Zadie Smith drops exclamation marks along with her guard, inviting an irresistible intimacy in her tone. They nudge at what George Saunders has played with for decades: that exclamation marks in prose can bring us closer to real-life communication if used to evoke blind optimism, self-determination or the air of a motivational speech.

Because life is more than full stops and pauses. It holds surprises and joy, wistfulness and laughter. For all the outrage and bluster of Donald Trump’s Twitter account, there is the irresistible glee of a toddler on TikTok. Good writers know this, and sometimes only an exclamation mark will do.