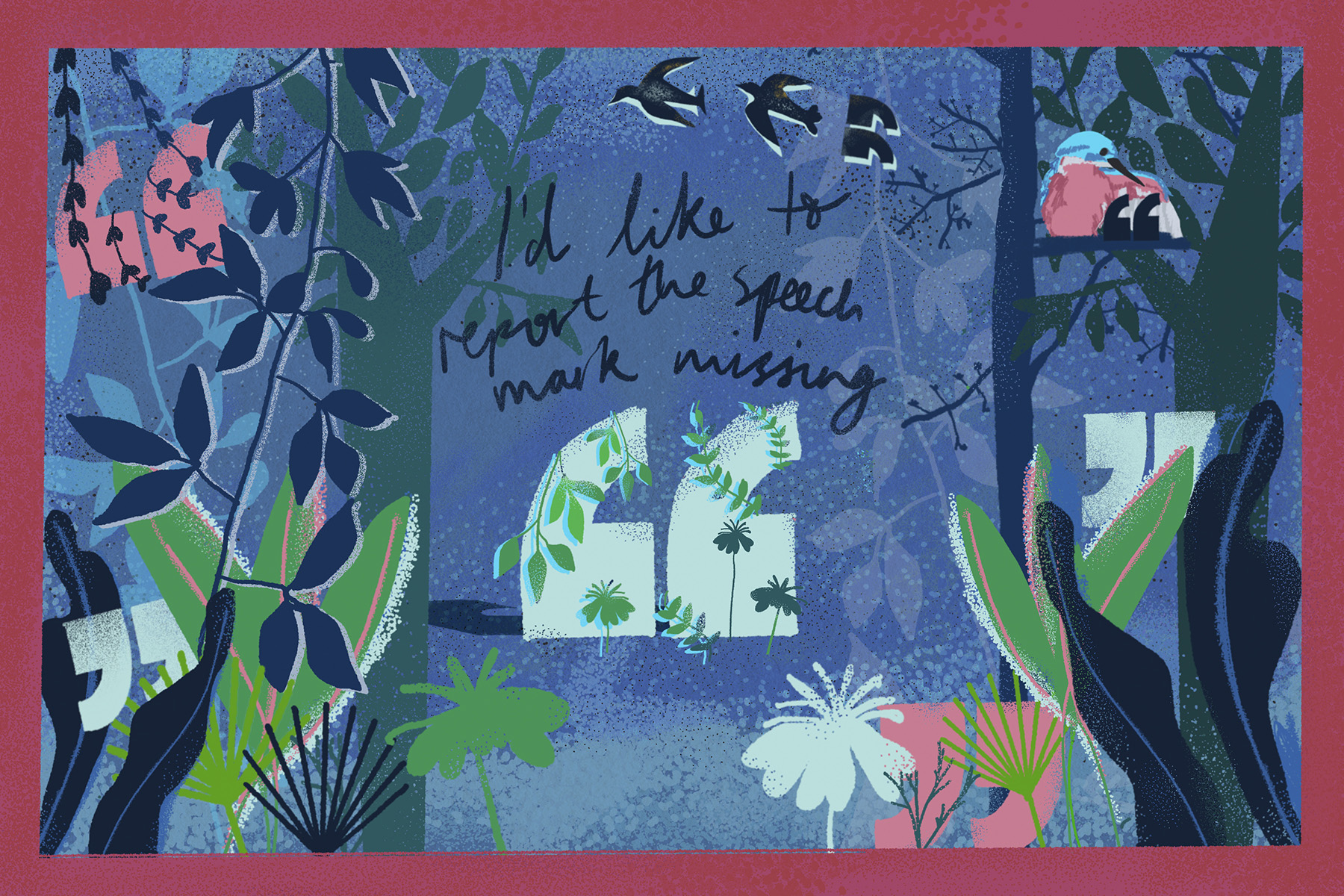

Does fiction still need speech marks? A potted history of vanishing punctuation

I’d like to report the speech mark missing. Punctuation goes in and out of fashion, and the marking of text with inverted commas to signify direct speech seems, in the current moment, to be decidedly out. A slew of contemporary novelists, from Ali Smith to Sally Rooney, have chosen to dispense with speech marks entirely, so that, punctuation wise, the dialogue blends with the rest of the text, as seen in Ali Smith’s Summer:

Are you a lover of art, Mr Gluck? Mr Uhlman says.

I know nothing about it, Mr Uhlman, Daniel says. My sister is sometimes a painter. But I know nothing.

Smith’s work gives Modernism and its flexibility with punctuation an afterlife. Modernists James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Samuel Beckett, Gertrude Stein and Dorothy Richardson were, after all, playing with and testing the limits of language almost exactly a century ago. Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, for instance, opens without them: Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.

Woolf did not dispense with speech marks entirely, but Richardson did – ostensibly on feminist principles. She wrote in 1938 that “feminine prose…should properly be unpunctuated, moving from point to point without formal obstructions”, but later appeared to regret omitting speech marks, saying she “felt like apologising to my readers”. She had, she felt, gained “a reputation for creating unnecessary difficulties” which was “very difficult to live down".

Cormac McCarthy said 'if you write properly you shouldn’t have to punctuate'

Experimental writers still face accusations of difficulty today, as some of the criticism around Anna Burns’ Booker-winning Milkman demonstrated in 2018 (arguably it is its style that contributes to its powerful momentum). Interestingly, Rooney has not faced similar accusations, probably because her prose is so clean, reminiscent of American writers such as J.D. Salinger and Lorrie Moore.

Though Rooney is one of the first novelists of her generation to dispense with the speech mark (and she is now joined by Rebecca Watson and Sophie Mackintosh), discussion as regards the marking of dialogue is longstanding among writers. Cormac McCarthy called them “weird little marks” and said that “I believe in periods, in capitals, in the occasional comma, and that’s it…if you write properly you shouldn’t have to punctuate”.

It’s easy to become wedded to certain ways of punctuating, but history tells us that our use of marks has always shifted and mutated. The origins of quotation marks lie in the diple (>), until the invention of the printing press saw the increased use of a pair of commas (",,") to indicate quotations. It was only with the advent of the novel and the drive for realism on the part of writers such as Daniel Defoe, Samuel Richardson and Henry Fielding that the use of quotation marks became standardised. And, as anyone who has studied French will tell you, other countries tend not to use them at all, favouring guillemets (« and ») or the horizontal dash, as in Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, and later used by Joyce.

'Using speechmarks felt like a breaking out of this ongoing flow'

Writers will make the creative decision not to punctuate for a variety of reasons. It suits stream of consciousness narratives, for example, because it is not as though we punctuate our own thoughts. Rebecca Watson, whose novel little scratch takes place in the mind of a young woman over the course of one day, uses italics. “Speech marks felt too disruptive on the page,” she tells me. “The ongoingness of a day in the life, a mind non-stop, unabbreviated, uninterrupted, present-tense requires far less punctuation. Using speechmarks felt like a breaking out of this ongoing flow.”

And then there’s the internet. To the interest of some linguists and the despair of others, the internet continues to transform our fluctuating use of punctuation. On Twitter or Instagram, users – particularly younger ones – rarely use full stops, quotation marks, and capital letters. Tutors report this bleeding into college essays, while bogus online grammar rationales have led to the increasing use of single quotation marks among students.

“Online has encouraged a levelling, or deformatting,” says Watson. “Say, on Twitter, where you have trolls, misogynists, sensitive thinkers, teenage climate activists and an imbecilic president, all in the same font and character limit. We are more used to sifting between tones and voices without needing huge signposts.”

This “context erosion” forms the underpinning of Patricia Lockwood’s novel No One is Talking About This. Written in fragments, it is peppered with memes and posts and references to online discourse interspersed with “real world” action and the thoughts and feelings of her protagonist. It could be complete chaos for the reader, but through a combination of the use of capitals, italics, font, free indirect discourse and – for offline conversations between people – speech marks, it makes a beautiful kind of sense. I suspect that in Lockwood’s case, the range of punctuation and formatting options allowed her to convey the essence of the internet without it becoming too disorientating, with the “meat space” conversations taking place within the safe bounds of quotation marks providing a pleasing counterpoint to the contextless virtual world she conjures.

So, contrary to what self-identifying language police may tell you, there are many different ways in which to punctuate, and what we do in one text may vary entirely in another. Sometimes writers will wrestle with the decision; Deborah Levy has written of wanting to discard speech marks in The Man Who Saw Everything, because “most of the contemporary writers I admired had skillfully ditched them and I knew this was the way to go.” But ultimately she decided to keep them because “things were wild enough” in her book. They would have to, she concluded, “be the Victorian swimsuit in my modernist novels".

Image by Alicia Fernandes/Penguin

What did you think of this article? Email editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk and let us know.