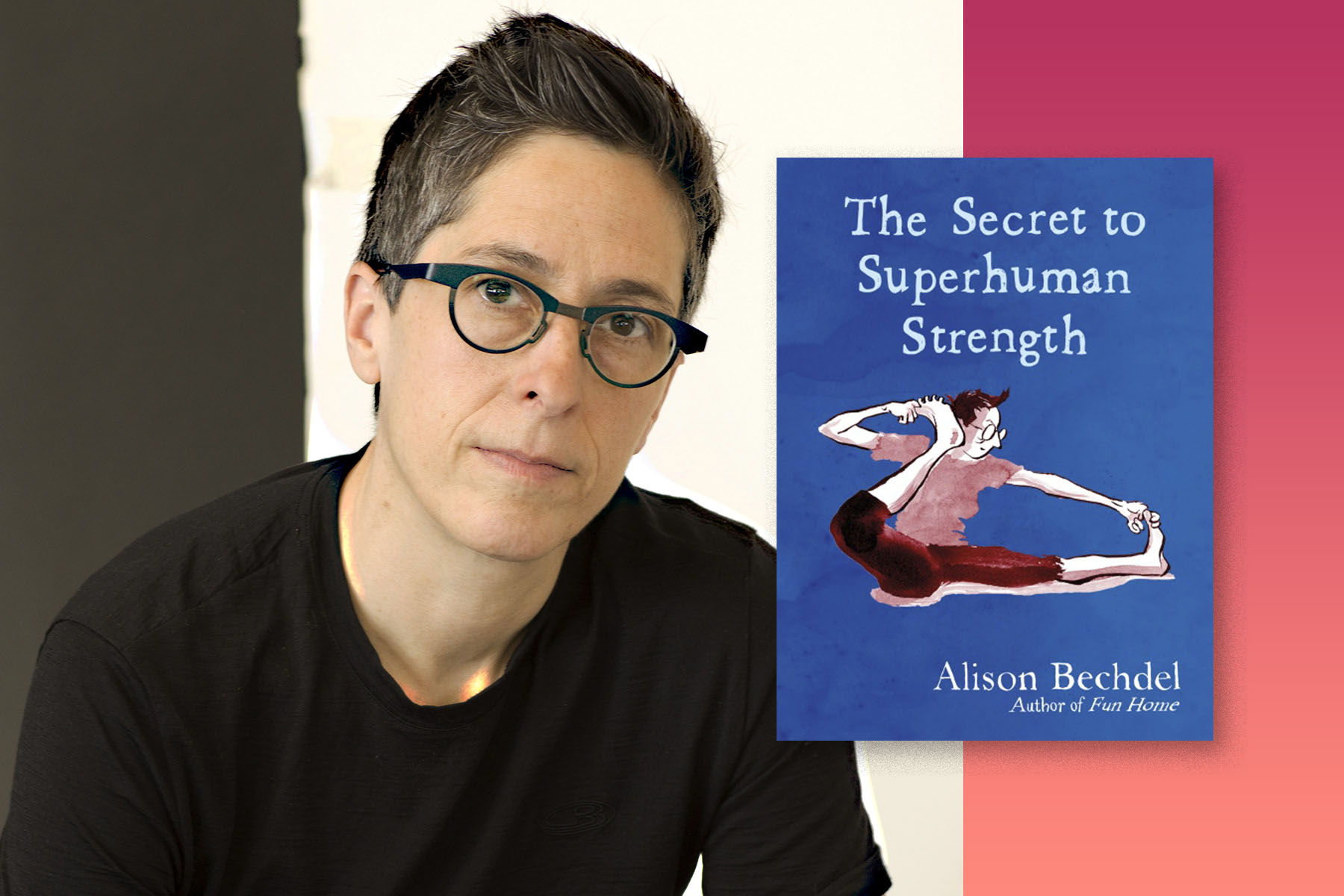

‘You have to let things die’: how Alison Bechdel’s exercise memoir became a matter of life and death

Eight years ago, the cartoonist and author of graphic novel Fun Home set out to write a light-hearted exploration of her relationship to fitness – but was she able to find The Secret to Superhuman Strength?

Tucked near the end of Alison Bechdel’s new graphic novel memoir, The Secret to Superhuman Strength, is a panel in which Bechdel blithely narrates that she’s starting a new project: “I began work on a new book, a light, fun memoir about my athletic life that I could bang out quickly.” The calendar on the wall in the illustration reads ‘January 2013’.

Somewhere between then and its new release, more than eight years later, the book fell more tonally in line with Bechdel’s first two graphic novels: 2006’s wryly titled Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, an autobiographical graphic novel that tracks her family upbringing, and her relationship to her father in particular, both leading up to and following his suicide; and 2012’s Are You My Mother?, a memoir in which Bechdel uses the work and theories of psychotherapists like Melanie Klein and Donald Winnicott to plumb her relationship with her mother, and the sources of her own neuroses.

Over the course of her career, Bechdel has established a penchant for poignantly written, deeply observant memoir. Her work has won numerous awards, and Bechdel herself – a 2014 MacArthur “Genius Grant” Fellowship recipient – has become one of the world’s most recognisable cartoonists. But though her comic strip, Dykes to Watch Out For, which chronicled the lives of a group of (mostly lesbian) friends, often took a genial tone, and she punctuates her books with humour, “light” and “fun” aren’t the first words anyone would use to describe her work.

'Going for regular runs helps me feel open and ready for when the creative flow comes'

“When I began the project,” Bechdel says now, over a Zoom call, “the idea was to do a book that would be quick and easy. I had just finished the second of two intense family memoirs – and I’m a cartoonist. I like to be light and funny, and I thought it was time to sort of switch gears a bit. Ultimately, this book turned out to not be so light.”

The Secret to Superhuman Strength has easily more levity than her other recent works, as evinced by the book’s introduction, in which a cartoon Bechdel bounces around the pages curling weights, high-kicking and cycling, explaining her lifelong role as “a bit of an exercise freak”. But as the pages flick by, so pile up references to the historical and literary figures whose intellectual frameworks will inform her own – William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller, Jack Kerouac, and Shunryū Suzuki, to name just a few – as well as the heady metaphysical themes and dualities that Bechdel will confront in the book: reality and transcendence, independence and interdependence, mind and body. “I’m not just writing about fitness,” she admits early on, but “how the pursuit of fitness has been a vehicle for me to something else; the feeling of the mind and body becoming one.”

But it’s the question of whether that vehicle is to something, as Bechdel says, or away from something, that provides the tension at the heart of Bechdel’s book. It is tempting to say that The Secret to Superhuman Strength is about death and the human desire to circumvent what she refers to as “that granite slab” – on some level, she claims early on in the book, exercise “afforded me the illusion that I might somehow stave off death” – but it might better be described as Bechdel’s journey towards understanding how to live a life.

'Finishing a book – especially a memoir – feels like a version of what death will be like, when you’re just done everything'

When creative flow won’t come to Bechdel, she says, “It’s very hard for me to cut myself some slack and say ‘You’re here, you’re putting in the time, that’s all you can do’. I know that intellectually, but I can’t help feeling a constant sense of falling short in my work when, like most days, inspiration doesn’t come. That’s part of why the book is about exercise: it’s a hack, a shortcut way to get some of that feeling. Going for regular runs helps me feel open and ready for when the flow comes.”

Bechdel’s fitness journey is almost never about physical fitness itself. It is, almost without fail, a means to an end, and that end is usually the transcendence of limitations. Throughout The Secret to Superhuman Strength, Bechdel uses physical activity to overcome not just creative block, but feelings of neurotic self-absorption, dependence on others, and breakups. Early in her life, she uses running to work through anger, and after her father’s suicide in her early 20s, immerses herself in karate to transcend the grief (“My only pain,” she notes while unbandaging her foot in the bath, “was physical”).

As a child, tempted by an advertisement in the back of a comic book, she attempts to transcend her self-perceived weakness by mailing away for ‘The Secret to Superhuman Strength’ – which turns out to be a poorly printed jiu-jitsu manual “laughably beyond the comprehension of a child”. That pivotal moment inspired the book’s title, as well as one of its most charmingly droll motifs: every time Bechdel manages to succeed in temporarily transcending herself, she wonders, “Is this it? Have I found the secret to superhuman strength?”

“These moments,” Bechdel tells me now, “are moments of liberation from myself. In so many ways, I’m my own worst enemy. Over the course of my life I’ve been in my own way and faced these various showdowns where I have to figure out how to get past myself. It’s funny; I think of the scene where I’m learning to do bodyweight exercises, like pull-ups and push-ups, using the weight of my own body to exercise, that feels psychologically important because I got strong enough to wrestle my actual self out of the way.”

'When I’m running or creating, I’m just being, in some stripped-down way'

Similarly, the transformation of The Secret to Superhuman Strength from “light, fun memoir” to a book-length metaphysical struggle reflects Bechdel’s own growth.

“In a way, that’s what I set out to do in the book: to convince or teach myself, to figure out for myself how to stop pushing so hard and start letting this stuff unfold in me.”

By the end of the writing process, she had achieved some semblance of clarity. Late in The Secret to Superhuman Strength, in a panel that hit so close to home I gasped, Bechdel muses about the process of finishing the book: “What if the point was not to finish”, she writes, “but to stop struggling?”

“Endings are so difficult because they’re kind of like death,” she says. “For me, finishing a book – especially a memoir – feels like a version of what death will be like, when you’re just done everything. Making creative choices is so finite; you’re letting go of other possibilities to say one thing. You have to let things go, let them die. I realised, in that panel, I’m talking not just about creativity but about life. Just… allow yourself to be. That’s the thing I have the most trouble with: it’s what happens when I’m running or creating; I’m just being, in some stripped-down way.”

Concerned that “this stuff kind of defies language” – “It’s hard to make sentences about what happens when your self disappears, in that realm where there is no subject or object”, she says – Bechdel points to a recent trip to the hospital for minor surgery as a moment in which was truly able to let go, to transcend.

“The day of the surgery, preparing for it and getting home from it, was the most blissful vacation I have had,” she pauses, laughing, “…ever. In my life. I just put everything aside and turned myself over to this bodily experience. It was so great. It’s sad to think I had to get an operation in order to reach that state of relaxation.”

Yet, after nearly a decade spent writing The Secret to Superhuman Strength, Bechdel takes some solace in her ability to notice and appreciate those moments. Is this, I ask, ‘the secret to superhuman strength’?

Bechdel laughs. “I’m not perfect, but I’m closer than I used to be.”

What did you think of this article? Email editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk and let us know.

Image: Ryan MacEachern / Penguin

Author photo: Elena Seibert