Che Guevara writes to his mother: ‘Revolution needs passion and audacity’

By July of 1956, Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara had seen enough to feel that Latin America would never be free of American neo-imperialism without armed struggle. In 1954, he’d watched as the democratically elected president of Guatemala, Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán was ousted – through propaganda and, ultimately, a series of bombing raids – by the U.S. government under Dwight Eisenhower.

The years in between were eventful. Through Hilda Gadea Acosta, a left-leaning Peruvian economist connected to Àrbenz, Guevara had befriended a number of like-minded Cuban exiles; by June of 1955, he’d met Fidel Castro, leader of the 26th of July Movement, whose aim was to overthrow the government of Fulgencio Batista, an American-backed Cuban dictator whose alignment with the wealthy elite had caused a rapid widening of Cuba’s wealth disparity and stagnation of its economy. Radicalised by the poverty he saw around him and the “cold premeditated aggression” he’d seen carried out by the United States – and after marring Hilda in September – Guevara was moved to join Castro’s group, and by the summer of 1956, he and Castro were plotting the 25 November 1956 assault on Cuban shores.

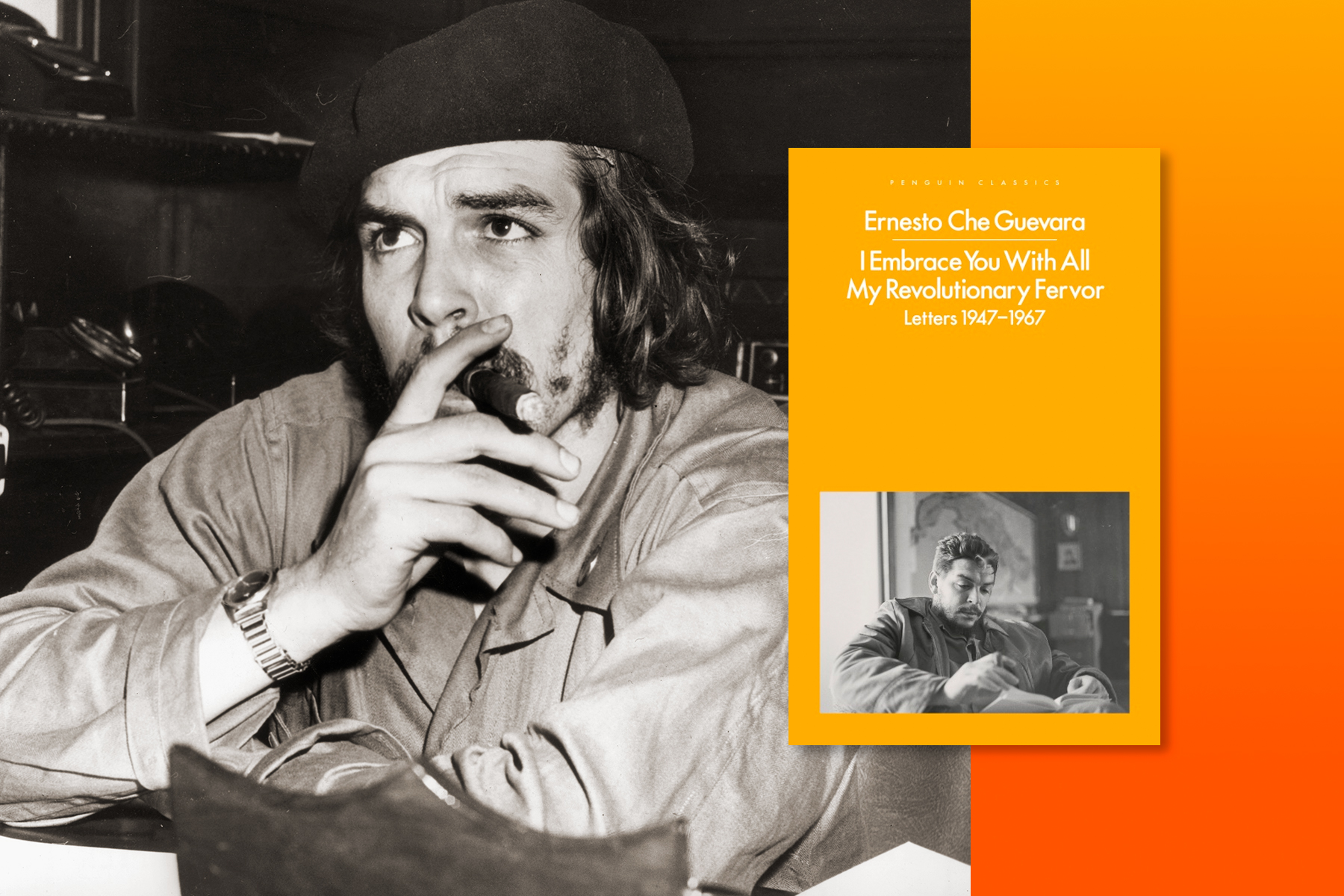

In this warm but forthright letter from I Embrace You With All My Revolutionary Fervor: Letters 1947-1967, sent to his mother from prison in Mexico just ahead of his release, Guevara is full of passion, humour and determination (and a few graphic images, too).

To Mother

Mexico [Miguel Schultz prison, July] 15, [1956]

Vieja,

I received your letter and it seems as though you have been experiencing a pretty bad bout of depression. It contains a lot of wisdom and many things I didn’t know about you.

I’m neither Christ nor a philanthropist, Vieja. I’m exactly the opposite of a Christ and philanthropy looks [illegible] to me, but I fight for what I believe in with all the weapons at my disposal, trying to lay out the other guy instead of letting myself get nailed to a cross or whatever. As for the hunger strike, you’re totally wrong. We started it twice and the first time they released 21 of the 24 detainees; the second time they announced that they would free Fidel Castro, the head of the Movement, and this will happen tomorrow; if they do what they say, only two of us will be left in prison. I don’t want you to believe, as Hilda suggests, that the two of us who remain have been sacrificed. We are simply the ones whose papers aren’t in order and so we can’t access the resources that our compañeros can.

My plan is to leave for the nearest country that will grant me asylum, which might be difficult given the inter-American notoriety I’ve now achieved. From there I’ll get ready for whenever my services are required. I’m telling you yet again that it’s possible I won’t be able to write for a quite a while.

What really distresses me is your lack of understanding about all this and your advice about moderation, selfishness, etc. – in other words, the most execrable qualities an individual can have.

Not only am I not moderate, but I shall try never to be so. And if I ever see in myself that the sacred flame has become a timid little votive flicker, the least I can do is to vomit on my own shit. As for your appeal to moderate selfishness, which means crass and spineless individualism (the virtues of X.X. — you know who), I have to say that I’ve tried hard to purge that from myself, not only of that unmentionable moderate being but the other one, the bohemian, unconcerned about his neighbor, filled with a sense of self sufficiency because of a consciousness, mistaken or otherwise, of his own strength. During this time in prison, and during the period of training, I totally identified with my compañeros in the struggle. I recall a phrase that I once thought was ridiculous, or at least strange, referring to such a total identification among members of a group of combatants to the effect that the idea of “I” was completely subsumed in the concept of “we.” It was a communist moral principle and naturally might look like doctrinaire exaggeration, but it was (and is) really beautiful to feel this sense of “we.”

(The splotches aren’t tears of blood but tomato juice.)

'Carnival is a culture that belongs in the hands of the rebels, the downtrodden and those at the bottom of the pigmentocracy'

You are deeply mistaken to believe that moderation or “moderate selfishness” gives rise to great inventions or works of art. All great work requires passion and the Revolution needs large doses of passion and audacity, things we possess collectively as humankind. Another strange thing I noted was your repeated mention of God the Father. I really hope you’re not reverting to the fold of your youth. I also warn you that the SOSs are to no avail: Petit shat himself, Lezica dodged the issue and gave Hilda (who went there against my orders) a sermon on the obligations of political asylum. Raúl Lynch behaved well from afar, and Padilla Nervo said they were different ministries. They would all help but only on the condition that I abjure my ideals. I don’t think you would prefer a living son who was a Barabbás rather than a son who died somewhere doing what he considered his duty.

These attempts to help only put pressure on them and me.

But you have some clever ideas (at least to my way of thinking), and the best of them is the matter of the interplanetary rocket – a word I like. Besides, there’s no doubt that, after righting the wrongs in Cuba, I’ll be off somewhere else; and it’s also certain that if I were to be locked up in some bureaucrat’s office or some allergy clinic, I’d be stuffed. All in all, I think that this pain, the pain of an aging mother who wants her son alive, is a feeling to be respected, and I should heed it and, more than that, I want to attend to it. I would love to see you, not just to console you, but also to console myself in my sporadic and shameful homesickness.

Vieja, I kiss you and promise to be with you if nothing else develops.

Your son,

- el Che

What did you think of this article? Let us know at editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk for a chance to appear in our reader’s letter page.

Photo above: Getty Images

Design: Mice Murphy/Penguin