- Home |

- Search Results |

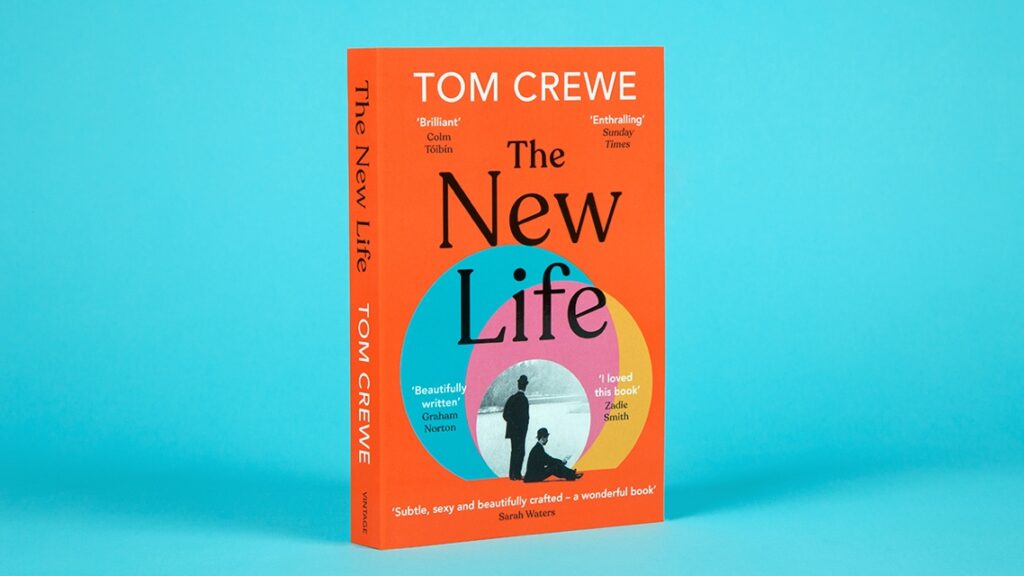

- The New Life by Tom Crewe: Extract

Two Victorian marriages. Two dangerous love affairs. One extraordinary partnership.

After a lifetime navigating his desires, John, married to Catherine, meets working-class printer Frank. Meanwhile Henry’s wife Edith has fallen for Angelica – and Angelica wants Edith all to herself.

John and Henry’s vision for the future brings them together to write a revolutionary book in defiance of convention and the law. Their book threatens to throw both men, and all those around them, into danger. How far should they go to win personal freedoms? And how high a price are they willing to pay for a new way of living?

Read on as John and Frank meet for the first time at the Serpentine swimming lake...

Hyde Park, 1894

The sun was stronger, the river leaching ever more of it into itself, so that the bobbing heads and shoulders had become almost indistinguishable, dark shapes on the diamond-cut water. There were fewer of them now. The grass was largely cleared of the mounds of caps, shirts, boots, trousers and drawers that had covered it. A trail of men led back towards the gate, where, if he concentrated, John could hear the dull chorus of traffic striking up. A man arrived, undressed with furious haste, and raced down to the water, throwing himself into it, arms looped over his head. He surfaced noisily, rubbing under his arms, sinking himself again, and then swam a few noisy strokes before returning to the shore, charging up it, towelling himself with determined energy, his glistening body shaking perceptibly. Finally, the tired clothes were pulled up and over. There was a poem in this, John thought. In this rapid transmutation from one thing, one century, to another, and then back again.

There was a poem in this, John thought. In this rapid transmutation from one thing, one century, to another, and then back again.

He watched the man depart, nimbling through the gold and green dapple. Then, once he could do so decently, he stood, putting away the book he had brought and brushing himself down, picking off individual stubs of grass. He turned onto the path, feeling, as always, relieved, but also wound to too high a pitch. His senses were pricked. The sunshine was harder and hotter.

A young man was at his side. John heard him only at the last moment – the onrush of his breathing.

‘My name’s Frank.’

He had clearly been in the water. His blond hair was dark and heavy with it, there was water beaded along his short moustache. His shirt was clinging to him in transparent patches. But John didn’t recognise him; hadn’t noticed him undress. Which dark shape had he been? Regret pierced him, even as he stood stock-still and fumbled for a response.

‘Can I help you?’

‘It’s a lovely day,’ the man said smilingly, rubbing the back of his neck. There was London in his accent, dragging on every word.

‘It is.’ John smiled back, and started to walk on toward the gate, as though this had been merely an exchange of pleasantries. He had been stopped before, never as many times as in his worst imaginings – only twice, in fact. Both times he had extricated himself quickly, almost run away, his head light and his pulse skipping. Neither time had the man been as beautiful as this.

Frank walked with him, stopping as he did. ‘I saw you watching. No, no–’

John had taken fright, set off again. He felt the man’s hand on his shoulder. The grip was gentle. He turned back, swallowing panic, looking into the beautiful face. ‘No, no,’ Frank repeated, something pained in his blue eyes. There was still water sheltering amid the hairs on his chest, visible at the opening of his shirt. ‘I saw you watching, nothing wrong with it. A lovely day. I only thought you might need a friend, keep you company.’

Frank smiled again; such a beautiful smile, the teeth a bright line under his moustache.

‘That’s kind,’ John said. He felt his strength returning with the absurdity of his response. Perhaps the man was only slow. Perhaps it was funny. He disbelieved these thoughts as soon as he had them.

‘Is it?’ Frank smiled again; such a beautiful smile, the teeth a bright line under his moustache. ‘It doesn’t feel that way to me. Though I do believe in kindness, sir. That is something I believe in. There’s precious little of it.’

People were walking past where they were islanded in the middle of the path. A dog hesitated over and dismissed John’s ankles. Frank seemed completely at his ease. John looked round, to reassure himself that the world was carrying on, that it remained to be got back to. ‘Well, thank you for the thought,’ he brought out. He looked at Frank as if for permission to leave. There was no answering movement in his face, which had become thoughtful.

‘Well shall we?’

‘Shall we what?’ The fear came back. Not the same fear exactly. He said it almost in a pant.

‘Be friends.’

John looked away at the three children scattering that moment around them, the mother lightly laughing an apology. It was as if this man in front of him were an invisible door and he was paused on the threshold.

‘There’s no hurry,’ Frank began again. ‘I’m sure you’ve things to be getting on with. I’m not idle myself, but you must be a busy man. Wait a moment – here’s my address.’ And he passed John a neatly folded piece of paper, taken from his pocket. He fixed John’s eye. ‘It’s not kindness though, sir. I don’t know exactly what it is, when you make a friend. But I don’t think it’s kindness.’

‘It’s not kindness though, sir. I don’t know exactly what it is, when you make a friend. But I don’t think it’s kindness.’

The paper was warm in John’s hand. ‘Well, thank you again,’ he said. He hated himself for saying this – felt that it wasn’t interesting enough, that this man would not be interested by it. But Frank was already stepping away.

‘Goodbye, sir. My reading’s good, if you choose to write. You should have no worry on that account.’

‘I won’t.’ John found himself smiling.

‘Well then. What a nice thing this is. And on a day like today.’ Frank pointed up to the sky with a grin. ‘I almost fancy another dip. Goodbye for now.’

‘Goodbye, Frank.’

As soon as he came out with it, he wondered at it: the use of the man’s name. As though they really were friends, as though what had just taken place could be blithely counted among the haphazard happenings of a day. Frank seemed to appreciate it. He grinned again, doing a strange little jump, his arms pressed to his sides.

‘Goodbye!’

And then he spun round and pretended to swim away along the path, bringing his arms up and over in alternating strokes, head bowed, cutting through the air. He didn’t look back to see whether John was laughing.