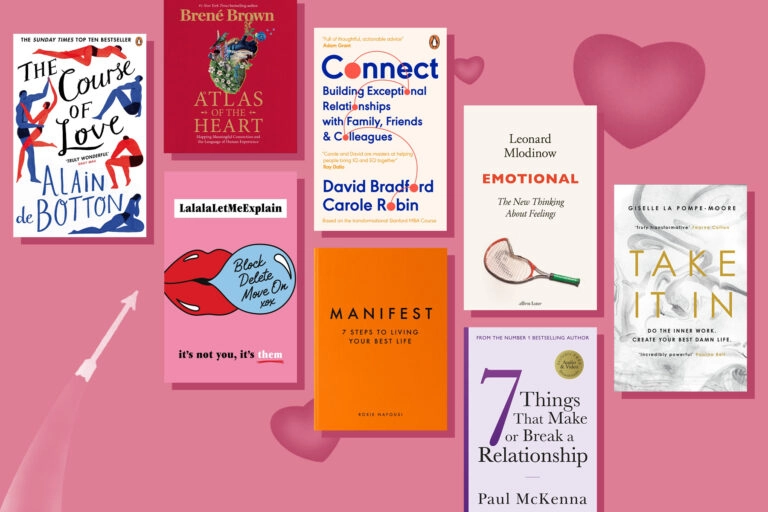

Self-help, health & well-being

Our spotlight authors

Sign up to the Penguin newsletter

For updates, exclusive content and more

By signing up, I confirm that I'm over 16. To find out what personal data we collect and how we use it, including for our recommendations, please visit our Privacy Policy.

Articles to inspire

About our self-help, health and well-being books

The best self-help books recognise that personal development – whether from mental health books, books about mindfulness, or self-improvement books – is an never-ending journey. Whether you’re looking for secrets to business success from Steven Bartlett or The Chimp Paradox, new modes of self-care from Why Has Nobody Told Me This Before?, or new life practices from guides like Atomic Habits, 12 Rules for Life, and Surrounded By Idiots, there’s a book to help you achieve your potential.