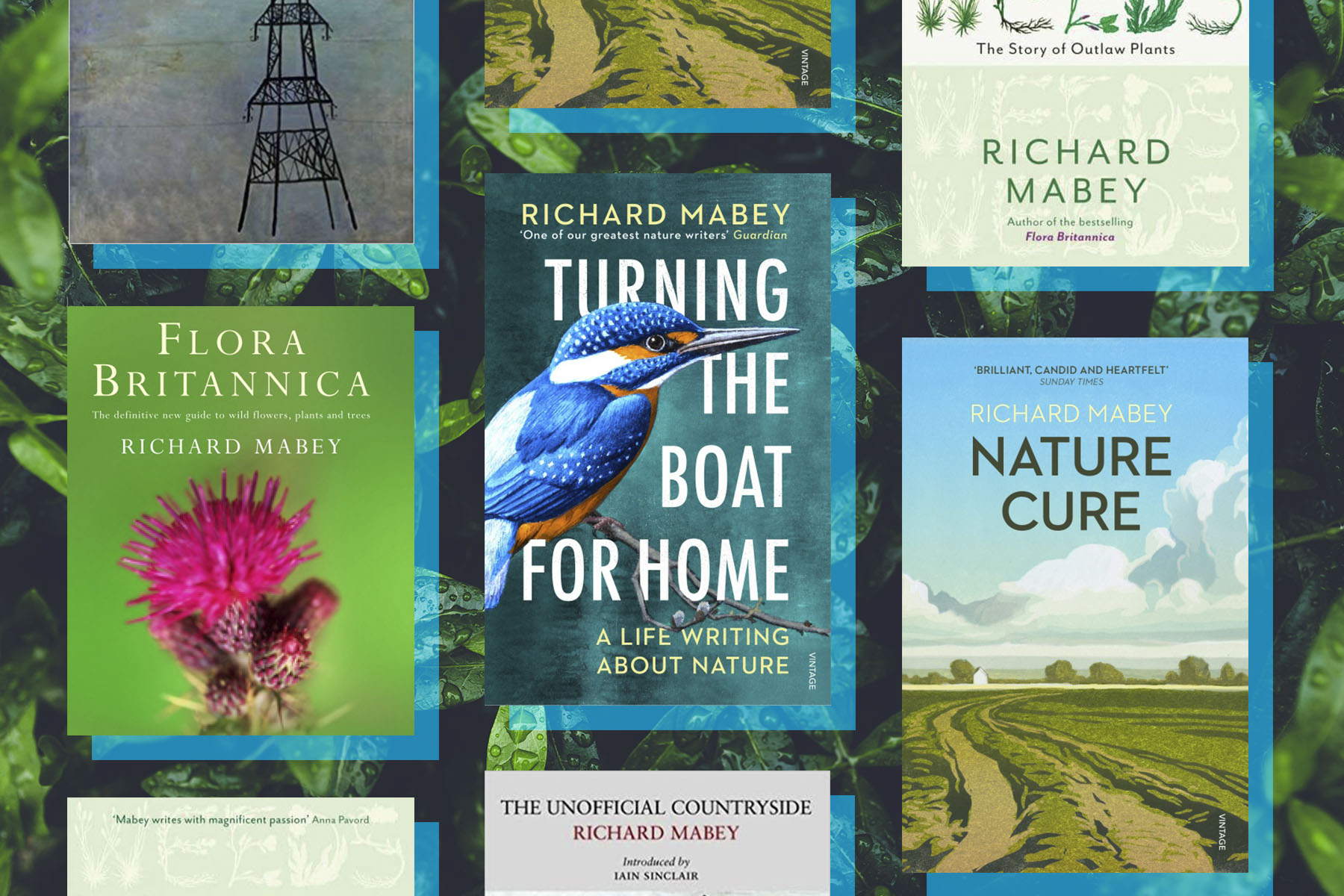

Richard Mabey

Praise for Turning the Boat for Home

Richard Mabey is among the best writers at work in Britain. I don't mean among the best nature writers, I mean the best writers, full stop. I would read anything he wrote, but if such a thing as nature writing ...

Tim Dee

One figure, like no other, looms large in setting the ground for the contemporary form that has come to be called then New Nature Writing. Richard Mabey is an author whose work has consistently pioneered new ways ...

Jos Smith

One of our most influential writers on the natural world

Gardens Illustrated

Richard Mabey is among the best writers at work in Britain. I don't mean among the best nature writers, I mean the best writers, full stop. I would read anything he wrote, but if such a thing as nature writing ...

Tim Dee

One figure, like no other, looms large in setting the ground for the contemporary form that has come to be called then New Nature Writing. Richard Mabey is an author whose work has consistently pioneered new ways ...

Jos Smith

One of our most influential writers on the natural world

Gardens Illustrated

Richard Mabey is among the best writers at work in Britain. I don't mean among the best nature writers, I mean the best writers, full stop. I would read anything he wrote, but if such a thing as nature writing ...

Tim Dee

One figure, like no other, looms large in setting the ground for the contemporary form that has come to be called then New Nature Writing. Richard Mabey is an author whose work has consistently pioneered new ways ...

Jos Smith

One of our most influential writers on the natural world

Gardens Illustrated