- Home |

- Search Results |

- The Pandemic Year

The Pandemic Year

Michael Rosen, Afua Hirsch and Jon Sopel join a range of Penguin authors, including doctors, teachers, midwives, scientists and more, to tell the story of Covid-19 and reflect on the tragedies, small victories and unsung heroes from 12 months that transformed the world.

It started with murmurs, then headlines; disbelief, scepticism; then cancellations, closures and, finally, on 23 March 2020, official orders from the government: “You must stay at home.” The novel coronavirus, Covid-19, was wreaking havoc across the country and the world, and to stop its spread, much of the world stopped, too.

Yet life went on: we worked, either from home or on ‘the frontline’; we took care of loved ones, the vulnerable; we watched as a pandemic exposed the cracks in society, shut down livelihoods. And death went on too, a constant, looming presence.

Here is the story of the pandemic year in the voices of people who saw its impact up close, whether in A&E, the classroom or in the corridors of power.

The pandemic expert: Mark Honigsbaum

Experts knew that there would be a pandemic at some point this century, but I don’t think any of us realised, in early January, that this outbreak in China would be ‘the big one’. The penny dropped when we saw those pictures of the quarantining in Wuhan, and the construction overnight of these huge hospitals lined with cubicles and empty cots ready for the deluge of patients. It was the third week of January.

Art Spiegelman’s comics masterpiece – a non-fiction memoir that tells the story about his father Vladek’s experience in the concentration camps during the Holocaust – remains the only graphic novel to have won the Pulitzer Prize, but that wasn’t enough to convince a Tennessee schoolboard to keep it on their curriculum. In January 2022, the McMinn County Board of Education voted 10-0 in favour of removing the book over concerns of “rough, objectionable language” and a drawing of a nude woman.

The book has long been a used to teach schoolchildren in America about the Second World War and the dangers of racism and anti-Semitism, but that wasn’t enough merit, apparently, to keep it in the school system – schoolboard doubled down on their decision the following month. In an interview with CNN about the decision, Spiegelman said “They’re totally focused on some bad words that are in the book. I can't believe the word 'damn' would get the book jettisoned out of the school on its own” and that he tries “to be tolerant of people who may possibly not be Nazis… maybe.”

Art Spiegelman’s comics masterpiece – a non-fiction memoir that tells the story about his father Vladek’s experience in the concentration camps during the Holocaust – remains the only graphic novel to have won the Pulitzer Prize, but that wasn’t enough to convince a Tennessee schoolboard to keep it on their curriculum. In January 2022, the McMinn County Board of Education voted 10-0 in favour of removing the book over concerns of “rough, objectionable language” and a drawing of a nude woman.

The book has long been a used to teach schoolchildren in America about the Second World War and the dangers of racism and anti-Semitism, but that wasn’t enough merit, apparently, to keep it in the school system – schoolboard doubled down on their decision the following month. In an interview with CNN about the decision, Spiegelman said “They’re totally focused on some bad words that are in the book. I can't believe the word 'damn' would get the book jettisoned out of the school on its own” and that he tries “to be tolerant of people who may possibly not be Nazis… maybe.”

A photo of cots lined up in a newly built A&E in Wuhan, China. Image: Getty

When I saw those images, they immediately brought to mind this iconic image from the 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic, an image taken at a US Army training camp in Kansas, in March of 1918, of row upon row of army recruits laid out on cots, called an influenza emergency room. My thought was, “This looks, and smells, and tastes like a pandemic. A big pandemic."

We weren’t getting good data out of China, and although we were tracking cases here and there, nobody knew that the virus has already reached Europe and North America, and was spreading under the radar. But by the weekend of Friday 21 February 2020, when suddenly we saw in Lombardy, Italy that towns were being quarantined, there was panic buying, and suddenly it was in the heart of Europe, that was the wake-up call.

By 23 March, the government had issued orders to stay home. At the end of the month, children’s author Michael Rosen was admitted to hospital with Covid-19. During his hospital stay, his 2008 poem, ‘These Are the Hands’, would become an unofficial anthem for NHS workers, and people countrywide were placing teddy bears, a reference to his book ‘We’re Going on a Bear Hunt’, in their home windows to brighten children’s moods on neighbourhood walks. Rosen wouldn’t know any of this until he awoke in June.

The patient: Michael Rosen

I can say that at the end of March I got Covid; I can say, at the end of June I came out of hospital. For me, what happened in between is up for discussion. I only have a zig-zag of memories in there.

What I do know is that while the UK was entering lockdown, I was in my own version of lockdown: I was unconscious. At that moment, doctors reckoned that the best way to get me over Covid was to sedate me and put me on a ventilator.

The midwife: Leah Hazard

“Call me again on this number when you’re outside the hospital,” I told her. “Put a mask on, but don’t leave your car. Don’t approach the entrance. Don’t touch anything. When you call me, I’ll come out and get you. I’ll look a bit like an astronaut in all my PPE,” I said, in a vain attempt to lighten the mood, “but don’t be scared.”

'I can say that at the end of March I got Covid; I can say, at the end of June I came out of hospital'

Don’t be scared. As if by saying the words out loud, I could will them to be true. It was April 2020, and she was my first Covid patient: heavily pregnant and becoming increasingly unwell at home, struggling to cope with full-body chills and lungs that had begun to grasp for air in short, goldfish gasps.

Many of my fellow midwives would take issue with the use of the word ‘patient’ for birthing women, but as I was soon to discover in the early days of the pandemic, many of these young, healthy women would indeed become ‘patients’, requiring intensive multidisciplinary teamwork and complex medical care in the face of an unknown disease. Midwives caring for Covid patients are always caring for two patients at any one given time: the mother and her foetus. Double the challenge, double the jeopardy. Don’t be scared: hollow words for patient and midwife alike.

By 20 March, schools were closed, leaving parents responsible not just for home care but home-schooling, too; teachers were left to figure out how best to do their jobs remotely.

The parenting coach: Daisy Dowling

The pandemic hit, the city was on lockdown, school was cancelled until who-knows-when and we were hunkered indoors. I kept my laptop propped on the kitchen counter so I could make book edits, help my six-year-old with her distance-learning worksheets, run my coaching business and make our family’s meals at the same time. Like every one of my clients, I was overwhelmed: working parenthood was already hard, but how on earth, I thought, are we supposed to manage it now, without schools, care, our regular support systems?

Each evening, as we leaned out the windows to bang pots and pans in support of the frontline workers coming off shift from the hospital two blocks away, I worried about the ones who have kids too – and wished I could somehow magically make enough noise to make this whole crisis end.

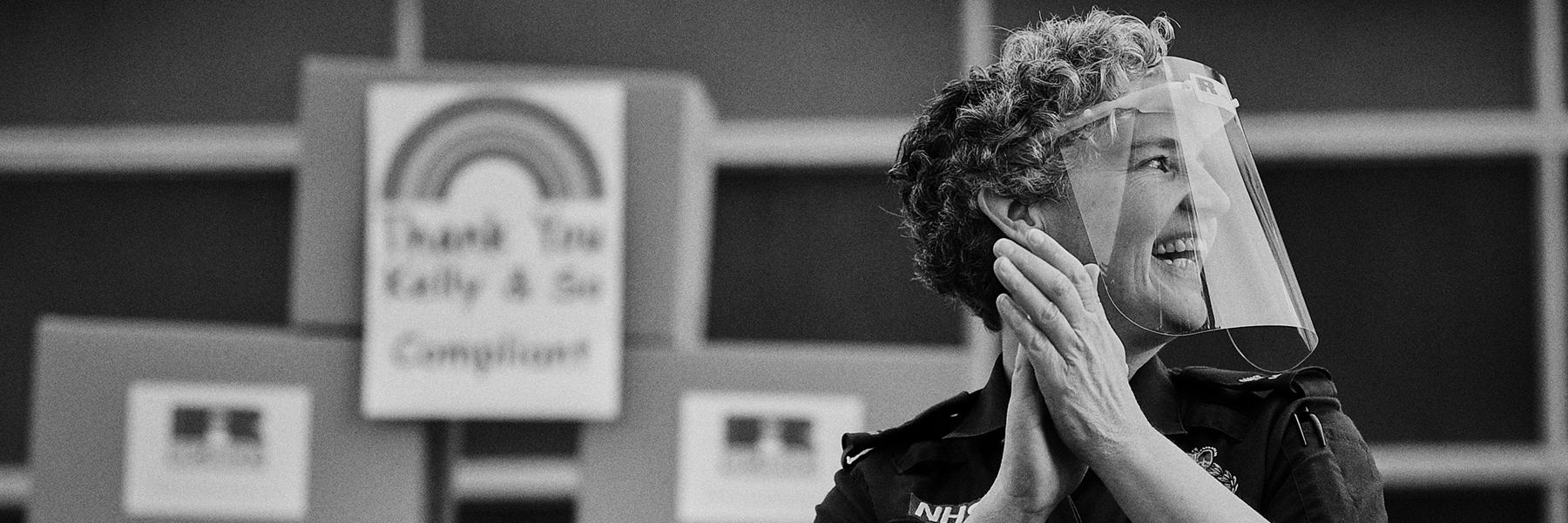

Nurses and citizens alike clapped for the NHS and frontline workers. Image: Getty

The working parent: Nell Frizzell

A month into lockdown last April, I stood on a patch of grass outside the closed Oxford University Museum of Natural History, my son holding his little collection of toy dinosaurs, wet-faced and heaving with grief by my side. I felt guilty, stranded and almost as sad as him. With libraries, playgrounds, nursery, museums and other children all suddenly out of bounds, I had no idea how I was going to occupy this tiny boy for the next few dragging months.

And there it occurred to me: maybe I could find Carl Harrington, the palaeontologist who discovered a plesiosaur skeleton at the bottom of a quarry outside Peterborough, and which was now on display inside the closed-up museum. Perhaps, by some miracle, I could dig him up from the internet. Tweets were sent, email addresses begged for and eventually I managed to send him a message.

And so it was that just days later – as I was burning with cabin fever, health anxiety, fear at what lay ahead and boredom – on a hot May afternoon, deep in the first national lockdown, I found myself sitting by a plastic tub full of sand, burying and reburying various miniature plastic triceratops, pterodactyls and ankylosaurus, weeping with gratitude over my phone. Like pure magic, there was Dr Carl Harrington, in a video, holding a little rubber dinosaur and a hand-drawn sign saying hello to my son. Beside our bucket. Telling us about his dinosaurs.

The school teacher: Amy Hampton

My school is in quite a disadvantaged area, so during the first lockdown lots of our children didn’t have devices to access remote learning. We felt disconnected from them, not being able to see them – it’s hard to engage online if you don’t have the facilities to do so, so they were completing work packs.

As a teacher, when you don’t have that connection with your students, you feel less like a teacher. That can be quite devastating. So what we did as a school, as many schools did, was create a video for our pupils to watch and spot their teachers being kind of silly.

I arranged it all, and when I was watching it I was so emotional; not only did it show how dedicated and committed those teachers were to reaching out to their pupils, it also showed what they were willing to do – whether it was hula-hooping in their garden or reading to their dog – to make that connection and bring that joy of learning back to their pupils. We wanted to show that, ‘Your teachers are human, and we’re feeling the same as you. We’re all going through this together. You’re not alone.’

Covid changed everything: suddenly just buying food was fraught with difficulty, while small businesses were facing increasing strain.

The home chef: Rukmini Iyer

I went to stay with my parents for three months during the first lockdown because I wasn’t sure when I’d see them again. Because they’re both older, I was in charge of the shop: I had them write a list for me, and I was getting food for other elderly people in their village, too, people who couldn’t manage that. It just felt very strange to suddenly do this supermarket sweep, and to know it was one shopping trip per week, maximum, because it would be irresponsible to leave our house more than that. There was no chance of getting anything delivered then.

Going to the supermarket felt like being on a military mission; you know, “I’ve got my list, my gloves, my hand sanitiser, my mask. I might have to queue outside but if I go at 3pm rather than noon maybe there won’t be a queue. Right, that person’s standing in front on the bag of salad, better keep a two-metre distance!” It was very strategic.

My parents cook from scratch, so our diet didn’t change much, but getting fresh veg was a challenge. If you cook South Asian, or Mediterranean cuisine, you need to find aubergines, say, or tomatoes. Having a little bit of cooking knowledge suddenly became very useful.

Shopping for groceries during the pandemic became a fraught ordeal. Image: Getty

The anti-social behaviour officer: Nick Pettigrew

For over a decade I was a local authority Anti-Social Behaviour Officer. To condense a career into a sentence: if people were doing bad things, I would investigate it and try to get them to stop. Lockdown showed me that how rules are communicated, whether it’s from the government or a court, is just as important as what those rules are.

After a year of doing my best to obey the numerous and often contradictory rules being issued by the government via press conference, leaks to journalists and hidden on parts of their website, I was reminded of things I’d heard in court when injunctions were breached by drug dealers: ‘It was just once’; ‘It’s a minor breach’; ‘I didn’t know that wasn’t allowed’. They are all things I’ll confess to having said during lockdown about the rules.

Clarity of language around limits and rules was something I’d underestimated; it can be the difference between people complying or lapsing back into behaviour that puts whole communities at risk.

The small business owner: Mary Portas

Just before the pandemic started, I gave a TED talk on The Kindness Economy. I talked about how the whole of consumer culture needs (and wants) to change, get better, put people and planet before profit – and the jeopardy businesses face ignoring this new and vital truth.

Fast-forward a few months and I found myself needing to turn all this vision into seat-of-pants action. The phone rings, and it’s my CEO Caireen. “Our clients in the States and in Australia have stopped work” she tells me. “Everything has shut down.”

'The business I’ve built up over two decades, my livelihood, is in freefall'

I’m standing in my kitchen realising that the retail consultancy business I’ve built up over two decades, my livelihood, is in freefall. This isn’t a stumble, a momentary loss of balance; it’s a lurching, nauseating heave to the ground. This is everything I believed was my financial safety falling and falling. And I’m not alone.

There is a Sufi teaching. You think that because you understand one, that you must therefore understand two because one and one make two. But you forget you must also understand the “and.” The and became my epiphany. Perhaps everything needed to fall down to make way for something better.

The patient: Michael Rosen

Picture me sitting in a wheelchair in the little scrap of a garden at the front of the old Victorian building that is now the St Pancras Rehabilitation Hospital. It’s June, the sun is out. My family has come to see me, and we sit with our masks and sunglasses on. The nurse who wheeled me here sits apart from us, being respectfully anonymous. Emma offers to trim my beard and cut my toenails. I feel ashamed that I can’t do this myself.

I can’t walk, either. I can’t stand up unaided. Emma explains that I’m ‘deconditioned’ from all that time I was in intensive care. I hear this but don’t ‘get’ it. I just hear that I was cared for intensively. I cast back through memories of lying awake at nights in wards with beeps and groans all around me, lights flashing on and off, nurses telling me to relax. Then we do photos, and agree that one of them looks like some kind of old vinyl record sleeve – I’m the old rocker in the middle. I tell them about the people in my ward upstairs: Ray the singer from Grenada, Dave who sold up and went on the road, and the guy I call Hagrid who fell out of bed. The sun shines on. I tell them that I’m learning how to stand up. My son asks me what do I do all day. I say, I don’t know – just think, mostly.

Later, I will learn how to use a ‘frame’, then a stick and, after three weeks of work in the gym with unbelievably kind and expert therapists, how to totter down the corridor to the loo, unaided, apart from urging myself on. In my mind I sing, “Search for the hero inside yourself.”

Overwhelmed NHS nurses worked tirelessly to take care of Covid patients. Image: Getty

By the summer, it had become clear that Covid was hitting vulnerable communities – elderly people, women, people of colour, and lower-income families – harder than others. The murder of George Floyd in the United States sparked worldwide protests against racism. The politics of the pandemic could not be ignored.

The activist: Alicia Garza

My life, and the lives of so many, will never be the same as they were before the Covid-19 pandemic. I remember reading an article in the New York Times that warned that the pandemic would mark an important shift in our everyday lives, to the scale and tune of how Americans’ lives were altered dramatically after the bombing of the World Trade Center.

Tragic events unify and divide. We are encouraged to do more to help our neighbours, to be connected. At the same time, we are drawn to be suspicious of one another, to demonise and place blame at the feet of those who most often are not responsible for what we’ve experienced. And just as 9/11 resulted in the demonisation of Muslims and Arabic people, the pandemic found Black communities being blamed for contracting and more frequently dying of this virus. Meanwhile, the former President of the United States had dubbed Covid “The China/Chinese Virus,” demonising Asian people.

'Just as 9/11 resulted in the demonisation of Muslims, the pandemic found Black people being blamed for contracting the virus.'

And then, in late May and June, the broadcasting of Black people being murdered by vigilantes and police, combined with the shuttering of my community, shaped my determination to fight back to ensure that we change the rules that have been rigged against Black communities. Tragedies are often openings for a shift in culture, a clarifying of values, and the remaking of rules; millions of others around the world made their voices heard to ensure our impact would be long-lasting.

In the US, Donald Trump’s erratic handling and politicising of the virus was wreaking havoc. Political correspondent Jon Sopel was on the ground as the US election approached.

The political journalist: Jon Sopel

It is a balmy, warm evening in Florida at Sanford airport, about 45 minutes outside of Orlando. It is less than a month out from the election and Donald Trump is holding a rally there. We are doing a report for the 10 O’Clock News, and just before I go live a group of guys make a point of coming over to where I am standing just to berate me. Why? Well, solely because I am wearing a face mask. “Why is it only you guys from the media that wear these stupid things?” asks one. “Just take it off,” another remonstrates aggressively with me.

Donald Trump has careered all over the road on this – once telling Americans it was their patriotic duty to wear a covering, but then sneering at a reporter who asked a question of him while wearing one, accusing him of being politically correct – and hardly ever wearing one himself.

My blood pressure is rising and I want to rail at these guys for their utter bone-headed stupidity. But I need to shoo them out of camera shot. And eventually they go and I am able to do my ‘spot’ on the bulletin.

From masks to social inequality, the pandemic became a political lightning rod. Image: Getty

A face mask may not be the golden bullet against Covid, but it’s not going to do anyone else any harm – and it may protect you and those around you. Yet the mere act of wearing one had – improbably – become freighted with political significance. Real Trump men, it seems, don’t wear face coverings. Only fake news scumbags like me and liberals do. How do you fight a pandemic when a face mask had become the new front in culture wars?

There are so many other incidents that I could talk about: being in the White House Briefing Room while Donald Trump mused on injecting bleach into the human body to kill Coronavirus stone dead (a special two-in-one offer where you would kill yourself stone dead too); the fairly constant undermining of Dr Anthony Fauci for his pesky insistence on sticking to the science; the inexplicable exhortation from the president for everyone to take Hydroxychloroquine, even though it had no medicinal benefits for treating Covid. But it was the consequences of the president’s muddled and mixed messaging that endured throughout the pandemic.

The young person: Caleb Azumah Nelson

The day before a new set of restrictions, in December 2020, I took a moment’s break from shooting a short film and found myself outside, alone, nostalgic and mournful. It was a bright, clear winter day; the sort of the day where, after wrapping up, we might pack into the corner of a pub, leaning over one another with drinks in hand, to laugh and tease, to tell stories and truths, to forge bonds and communities.

'The mere act of wearing a mask became freighted with political significance.'

When that pub closed, we might spill into another bar, or find somewhere to dance, or maybe someone lives close and we would make the short walk towards theirs, taking a perch on any and every available surface in their living room, laughter continuing to echo through the room. We might compare notes about our plans for Christmas, or New Year’s Eve, and beyond.

I miss being out in the world. I miss a busy London street beneath my feet. I miss chance meetings with friends, spontaneous bonding with strangers. I miss it all. A member of the crew walked past as I was imagining these possibilities and I shared how I was feeling. He was feeling the same, but reminded me that this won’t last forever.

There are better times coming. Whenever I remember this conversation, it makes me hopeful for a time where we can gather again.

The ‘time to gather’ was supposed to be 25 December: Boris Johnson implemented a strict lockdown in November in a bid to “Save Christmas”. It failed. On 20 December the government implemented rules that effectively cancelled cross-household Christmas celebrations. And coronavirus cases continued to worsen.

The Christmas case: Nikita Lalwani

It was 28 December 2020. The timing of my illness was telling: despite continued messaging about ‘saving Christmas’, the government’s vague, often contradictory Covid rules meant that we were in the sudden U-turn of Tier 4 lockdown in London. I was part of the daily increase in positive cases that season, and when my oxygen levels dipped now and then, I was fearful of the possibility of hospital. NHS staff were battling with large numbers of patients coming through the door. Within days the death rate would go over 1,300 a day, and continue climbing.

'This was the moment we turned the corner and began to see the light at the end of the tunnel.'

I was sitting in bed, with glazed eyes and mind, holding a book that I could hardly be said to be reading – I had been stuck on the opening page for a couple of days. My nine-year-old son came into the room and asked if he could do ‘joint reading’ with me. I agreed, and he proceeded to tuck himself in and commence his project: to read out loud from a book entitled 1,000 Good Jokes. In the beginning, I think he expected a reaction; he soon realised he wasn’t going to get one from the zombie next to him. But his sporadic laughter, the contented enjoyment of his continued presence, his optimism, I guess – it was infectious and a little humbling. It broke me out of myself. I could see in his eyes the knowledge that things were actually, very probably, at least in this case, going to be OK.

And yet, against the odds, within a year of lockdown, vaccines had begun to be administered. On 8 December 2020, 91-year-old Margaret Keenan was the first person in the UK to be given the Pfizer Covid-19 jab in a hospital in Coventry.

The pandemic expert: Mark Honigsbaum

This was the moment we turned the corner and began to see the light at the end of the tunnel: the rollout of the vaccine. I’ve got an 89-year-old mother who shielded throughout the year, and on 31 December, she got the call to get her first jab. That was very emotional.

Margaret Keenan, 91, was the first person in the UK to be given the Pfizer Covid-19 jab. Image: Getty

There’s so much our government botched, but the one thing we’ve been good at is distributing vaccines. It’s the thing we can really applaud ourselves for. Though I still remember, on 3 March, that first Downing Street press conference, when Boris Johnson was asked whether he would still be shaking hands and he said: “I shook hands with everybody, you'll be pleased to know.”

The journalist: Afua Hirsch

In January this year, a doctor in the north of England reported vulnerable patients were turning down the chance to have the Pfizer coronavirus vaccine because they wanted to “wait for the English one”. The comments prompted many to condemn those vulnerable patients as stupid people who, despite being highly at risk of Covid, would let misplaced patriotism get in the way of their treatment.

But I was not among them. In fact, their scepticism seemed a very rational response to a year in which British people were constantly pumped with fantastic nonsense about how superior everything we did was.

From the outset, the government said Britain’s response to Covid would be the “best in the world”, yet as early as March 2020 it emerged that frontline NHS staff were dying from substandard protective equipment. That May, Boris Johnson said that Britain’s track and trace system would be “world beating”; in fact it was quietly forgotten as an epic failure. Throughout the year, the British people were told to feel superior, whilst our deaths from Covid surpassed almost all other nations.

After a pandemic that by definition knows no borders, and which Britain lamentably failed to control, vulnerable people were refusing a vaccine because they were told that only Britain was capable of excellence. It really is a case study in how the main victims of the British government’s delusions are the citizens themselves.

Despite the increase in vaccinations, January and February saw a catastrophic new wave of cases, as mutant variants of the virus began to spread. The NHS was being overwhelmed.

The ICU doctor: Jim Down

'I was heading into a four-day run of 13-hour shifts. We were past the peak, but still caring for well over one hundred ICU patients.'

It was 7am on 8 February 2021, and the temperature was -2. A smattering of snow covered the car and as I inched down the hill towards the main road, I was anxious that I might glide gently into the oncoming 214 bus. The first item on the news was, inevitably, Covid. A small study suggested that the Oxford vaccine had only 10% efficacy against the new South African variant. It might reduce deaths but it didn’t prevent the disease.

I was heading into a four-day run of 13-hour shifts. We were past the peak, but still caring for well over 100 ICU patients. In many ways the second surge was just like the first, only more so. We were better organised but there weren’t any more ICU nurses so they were, again, responsible for three or sometimes four critically sick patients instead of their usual one. And the disease itself hadn’t changed; some people still recovered on the tight CPAP masks, others became very sick very quickly and died and many were critically ill and unstable for weeks. One, in particular, was staying with me.

Because more than half of our Covid patients were transferred in from other hospitals, already ventilated, we never typically met them awake, but in mid-January I looked after a woman in her early-70s on CPAP. Six months previously, she’d cycled 20 miles along the Suffolk coast, but she had Type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure, and just before the new year she contracted Covid. She knew that, once ventilated, her chances were not good, so she was determined to do everything possible to avoid it. She understood the situation, and as I worked with her, we connected.

She did everything she could but couldn’t change the trajectory. Two days later, we put her to sleep and took over. Initially she was stable: I spoke to her husband every day and was cautiously optimistic. But then, as so often, this brutal disease took its grip and tore through her body’s defences. On 6 February, she became yet another victim of Covid-19, and it hit me hard. Having learnt from the first wave, a part of me thought that if we just hung in there we’d be able to get more of the patients through this time.

The vaccine provided a light at the end of the tunnel, but a new wave was hitting the country in the early months of 2021. Image: Getty

So I’d pinned my hopes on the vaccines. I’d gratefully grabbed mine at the first opportunity, and saw it as the light at the end of the tunnel, the route back to normality. I could do this for a few more weeks – months even, if I had to – as long as there was an end to it. But by 7am on 8 February, serious doubts crept in to my mind. Vaccines would still be vital, but new variants might well mean that we’d need to continually adapt them. We might be playing whack-a-mole with Covid-19 for years and the new normal might be very different to the old.

The grief psychotherapist: Julia Samuel

I have seen greater levels of suffering this year than I have ever witnessed in all of my working life. This is true for my clients in my psychotherapy practice, the staff at the hospital I support, the webinars where I speak and respond to questions, my Instagram followers, and my friends. It has been intense.

It has also been profoundly rewarding, where I have felt that everything I have learned about grief, love and humanity has come together and been useful. In my therapy practice I see a young woman whose mother died last summer of Covid-19. Her grief is more painful and prolonged because the death was sudden and unexpected. For months she was in shock whilst screaming out in the pain of missing her.

'Every day I am deluged with requests for therapy or advice and support.'

Due to lockdown, she hadn’t seen her mum for months, then couldn’t see her when she was dying, nor say goodbye when she died. Regrets and images of the future she won’t have wheel in her mind and can at times make her feel like she is going mad. Yet she is finding her way to live with it. She is already beginning to experience moments of joy.

Every day I am deluged with requests for therapy or advice and support. I respond and refer on as best I can but I am troubled by the level of need and the lack of what is available. My hope is that our community will come together with compassion and live more connected loving lives.

By spring, as vaccines continued to be administered in record numbers, a sense of optimism – or, at least, a sense that an end was in sight – began to settle. A sense of what we may have learned, and what we could change after the pandemic began to emerge.

The parenting coach: Daisy Dowling

A year later, the pandemic continues. Working mums and dads are strained and stretched – we all are – but something fundamental has changed, too. My coaches have stopped apologising when a toddler interrupts a Zoom. Working parents’ networks are sprouting up inside every type of organisation. As hardworking parents, we don’t just want the crisis to end: we want better – and the tools, new approaches, and connections to one another that will help us get there.

The economist: Jason Hickel

As the reality of the pandemic sank in, the world of economics turned upside down. For more than half a century we've been told we need constant growth, growth, growth, even though we know it is driving ecological breakdown, so I was shocked when, in order to protect public health, many governments started slowing down huge parts of the economy and even closing whole sectors: it felt like the planet finally had a chance to breathe again.

Yet it was hardly worth celebrating, because the social consequences were devastating. Many of the affected sectors were vital to people’s lives and well-being: schools, gyms, sports facilities, cafes, art museums and other spaces of conviviality.

Business closures wreaked havoc on the economy, but prompted the question of how to come back better. Image: Getty

The lockdowns revealed that we're stuck in a catch-22, but I think there’s a way out. I remember thinking to myself, “Now that we have the power to slow down the economy, what would happen if, after the pandemic, we used it differently?”

What if instead of scaling down socially necessary parts of the economy, we scaled down parts that we really don’t need at all? Imagine if we scaled down sectors like SUVs, arms, industrial beef, fast fashion and advertising. Imagine if we reduced the number of private cars and improved our public transportation networks instead. Imagine if we banned planned obsolescence and introduced a ‘right to repair’ for electronics and appliances, so we wouldn’t have to produce as much stuff.

Measures like these would help bring our economy back into balance with the living world, while allowing us to keep what’s actually important. Our economy would require less labour, so we could shorten the working week, share necessary work more evenly, and distribute income more fairly. We could reap the benefits in the form of free time: more time to spend with our loved ones, and more time to spend learning, creating, exercising, caring, getting to know our neighbours – things we’ve all learned to appreciate more over the past year.

Lockdowns are terrible, and it will be nice to have them behind us. But I like to think there's something we can learn from this catastrophe that could change the world for the better.

The small business owner: Mary Portas

'This is our task now: to retire the old structures of growth and greed whilst bringing in the new of generosity and good.'

When you have no choice but to rebuild, your default assumptions get stripped away and all you’re left with are the important questions. What kind of business and world do I want to create? Yes, there’s pain and fear, but there’s also an opportunity to do things differently. To forge a new path.

This is our task now. To retire the old structures of growth and greed whilst bringing in the new of generosity and good. This is our opportunity, our life raft. And it’s exciting, scary and exhilarating.

The patient: Michael Rosen

When I come home, my wife Emma explains to me again – and again – that I was in intensive care. She explains that I was unconscious.

“I was unconscious?” I say.

“Yes, you were unconscious… for about seven weeks… April into May.”

“Was I?”

Well, I remember the bit where Emma and our daughter Elsie take me A&E late one night – and that was March. And then there’s a blank, a nothing, until the beginning of June and a memory of a ward where a nurse is telling me in the middle of the night, with beeps beeping and lights winking, not to pull a tube out of my nose…

'I was ‘dead to the world’, I say to myself now. But not dead.'

For seven weeks, Emma says again, as patiently as she can, she didn’t know if I would live. Finally, I see myself as a body, with tubes running into me, feeding me, supporting me, while my microbiology beavers away trying to cope with the viral invasion.

I was ‘dead to the world’, I say to myself. I ponder on it: dead is dead, but this isn’t that. ‘Dead to the world’ is only dead to what’s going on out there – but I’m not dead. Not yet.

The pandemic expert: Mark Honigsbaum

For the vast majority of the population, history suggests that once the pandemic is over, amnesia sets in quite quickly. We’re not very good at remembering things that happened last year, never mind five years ago; we live in an eternal present. The 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic was known for a long time as the forgotten pandemic. It’s understandable: having been through such a difficult period, emotionally and psychologically, it’s human instinct not to want to linger and remember those periods of suffering.

But I think you have to distinguish between the majority and those who have been directly affected – in other words, those who have lost a family member or friend to Covid-19, which is something like 1 in 600 people in Britain. For those who had that experience, this period is something that will forever be seared in their memory; that sort of grief you can come to terms with, but you can’t get over it. The bereaved will have questions that haven’t been answered; they’re not just dealing with grief and trauma, but with anger. To get closure and move on, there will have to be a public enquiry, a process of accounting, a political reckoning. And once the health crisis is over, we’re going to be living with the economic and political fallout. This will require massive reconstruction.

Amidst a year of death, new life provides a reminder there is reason to carry on. Image: Getty

The midwife: Leah Hazard

The NHS and the wider world are still engaged in hand-to-hand combat with Covid, but like the dozens of women who continue to walk, stagger, crawl and stumble through the doors of my workplace every day, our urge to create and sustain life is unstoppable. We try to heed our own advice – to look fear in the eye and move past it – and we search for green shoots, new beginnings and better times ahead.

And sometimes, we find them: after waging war against an illness that seemed at times like it would be insurmountable, my ‘patient’ – if I can call her that – went on to deliver a healthy baby.

What did you think of this article? Email editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk and let us know.

Read our Reasons for Hope essay series which is raising money for the National Literacy Trust to support families affected by Covid-19.

With deepest gratitude to our contributing authors, in order of appearance:

Mark Honigsbaum is a medical historian and journalist, and the author of The Pandemic Century.

Leah Hazard is an NHS midwife and the author of Hard Pushed: A Midwife’s Story.

Daisy Dowling is the founder of Workparent, which offers support and resources to working parents, and the author of Workparent: Thrive in Your Career While Raising Happy Children.

Nell Frizzell is a writer and journalist, and the author of The Panic Years.

Amy Hampton is a teacher at Park End Primary School in Middlesbrough and is a participant in Puffin World of Stories.

Rukmini Iyer is a chef and the author of The Green Barbecue and the Roasting Tin series.

Nick Pettigrew is a writer and former Anti-Social Behaviour Officer, and the author of Anti-Social.

Mary Portas is a broadcaster and businesswoman, and the author of the forthcoming Rebuild: How to Do Business Better.

Alicia Garza is an activist and strategist, the co-creator of #BlackLivesMatter, and the author of The Purpose of Power: How to Build Movements for the 21st Century.

Jon Sopel is a reporter and the BBC’s North America Editor, and the author of UnPresidented: Politics, pandemics and the race that Trumped all others.

Caleb Azumah Nelson is a writer and photographer, and the author of Open Water.

Nikita Lalwani is a writer and the author of You People.

Afua Hirsch is a writer, journalist and broadcaster, and the author of Brit(ish).

Jim Down is a consultant in critical care and anaesthesia at University College London Hospitals, and the author of Life Support: Diary of an ICU Doctor on the Frontline of the Covid Crisis.

Julia Samuel is a psychotherapist and the author of This Too Shall Pass.

Jason Hickel is an economic anthropologist and the author of Less Is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World.

Image at top: Mica Murphy / Penguin