In 2018, Michelle Obama’s autobiography, Becoming, transcended the usual celebrity memoir to become an immediate worldwide hit. Her story of her upbringing in Chicago, her law career, and her role as First Lady to America’s first Black President, Barack Obama, was as loved by book club readers as it was by activists, with lines becoming much-repeated Instagram quotes.

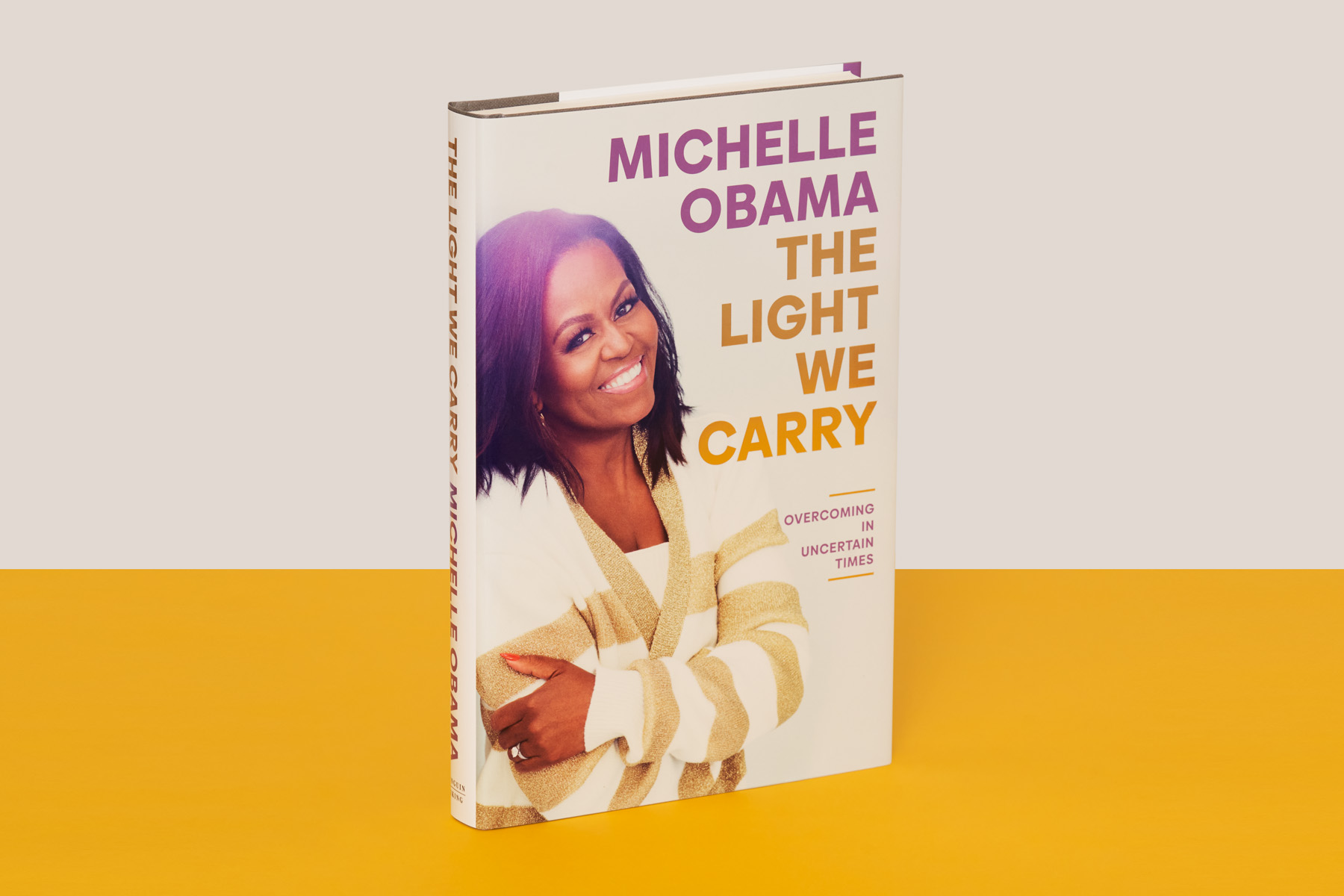

Her new book, The Light We Carry, deftly combines further autobiography with the wisdom and insight that she has gained – not only through her own experience, but the people she has met, and read, throughout her extraordinary career. These range from the young women she has mentored (and whom she credits for keeping her curious) to inspirational leaders such as Toni Morrison.

“I originally conceived of this book as something that would offer a form of companionship to readers going through periods of flux – useful and steadying, I hoped,” she says. Obama hoped to reach out to people going through grief or graduation, birth or loss, from the viewpoint of her nearly 60 years. “I should have known better, of course,” she says wryly – and of course, nobody could have predicted the times we have lived through since Becoming.

But keeping things running through extraordinary times is what Obama knows. She also includes several pieces of advice from her own mother, the remarkable Marian Shields Robinson, who spent Obama’s Presidency in the White House keeping the family running before moving back home when the family moved out.

This book is remarkable both for its reiteration of Obama’s service to America and how she reframed the role of First Lady – something one can only truly appreciate in hindsight. She only names Barack Obama’s successor once, but the horror with which she viewed his impact on the country is evident. Obama may have become known for her line, “When they go low, we go high,” but her final chapters show what that means in practise – the very opposite of lie down and roll over.

How to go high, even now

It's not about slogans or t-shirts, but true hard work. "In the end, at least in my experience, what you put out for others – whether it's hope or hatred – will only create more of the same,” says Obama. So anger needs to be harnessed to make something more lasting than noise: budgeting your energy carefully, so that you aren’t distracted from what is important by noise. Be fit, be strategic. Sleep and eat well. Keep your armour up. Feed your sense of happiness and stability. During times of flux, remember that small power can be meaningful power: voting, joining a cause, helping a neighbour, being visibly glad to see someone. “But more than anything,” adds Obama, “don’t forget to do the work.”

How to stop your fearful mind from taking over

Obama’s pragmatic parents taught Michelle and her brother, Craig, how to discern what to be truly frightened of from a young age: “to help us figure out what was frightening us, and what was holding us back”. The family motto may as well have been, "Go forth with a spoonful of fear and return with a wagonful of competence", whether it was five-year-old Obama walking to school alone or saying yes in 2007 to her husband running for presidency. “Doubt comes from within,” she says. “Your fearful mind is almost always trying to seize the wheel and change your course.” She describes her fear voice as “every monster I have ever known” but that, crucially, “she is also me”. That part of you would rather you comfortably stayed at home and didn’t say yes to that date, travelling abroad, or stepping into a room of new people. When that voice appears, Obama doesn’t ignore it and let it get louder: she addresses it gently. Oh hello. It's you again. Thanks for showing up. For making me so alert. But I see you. You're no monster to me.

Enjoy the 'pleasure of a small feat'

Letting her hands take control and leaving her “brain trailing behind” gave Obama’s mind some respite from anxiety during lockdown. It helped her to refocus while watching the ongoing chaos of Donald Trump’s presidency unfold and to clarify her thoughts into a rallying speech at a time when all she felt was turmoil. Giving herself over to the tiny and precise movements of knitting, “something smaller than that fear”, allowed her to move back towards hope; letting her thoughts roam led her towards her parents and ancestors, made her aware of how previous generations had also had to “mend, fix, and carry over time”, with the aim of making things better for their children and their children’s children. Knitting won’t eliminate racism, she says, but the point is to find something small but active, to stand along the things that seem unimaginably big: to allow yourself the gift of absorption and some respite in the pleasure of a small feat.

What it means to be an 'only'

As a tall child – 5ft 11in by 16 – Obama became used to standing out, but without the role models of sport and culture that exist now, she spent energy compensating for what she wasn’t. Letting in the voices of others allowed them to become self-consciousness – which runs close to self-sabotage. When she moved from her Black neighbourhood in Chicago to the overwhelmingly white, male, rich halls of Princeton, she found herself an “only”: “your own reality seems vanished”. Obama found strength through her council of other Princeton “onlys”, many of whom became lifelong friends. Her father’s motto, “No one can make you feel bad if you feel good about yourself” took years to sink in, but acceptance was crucial to Obama being able to take up space with pride and to find an inner steadiness to help keep her moving – especially when old narratives say, ‘I don’t see you as being entitled to what you have’. Remembering a school guidance counsellor who dismissed her as “not being Princeton material”, Obama says: “My life became a kind of reply: Your limits are not mine.” These limits, she says, remind us why we persist. And sharing these stories can help us to find community and learn that we aren’t the “only” after all.

The importance of 'starting kind'

Obama remembers learning that her friend's husband, Ron, the former mayor of a big city, starts every day by greeting himself in the mirror with a cheery, “Heeeey Buddy!” There’s no assessment or critique. It’s just quite kind. It’s reminiscent of being a child and remembering how delightful it is to see something glad to see you. Obama has taken her lead from Ron: now, she lets any critical morning thoughts slide out of her head, and replaces it with a more intentional, gentler one. Keeping the bar low is powerful and stabilising: "You're here, and that's a happy miracle, so let's get after it."

How to make (and keep) friends at any age

During her husband’s presidency, Obama invited friends for regular weekends at Camp David to spend time together and get fit. One time, there was mutiny over Obama’s initial plans to ban snacks and wine (this was swiftly overturned: “You’re crazy if you think you get to make all the rules.”) Showing up is key to friendship; as is having a couple of solid friends where you are invested in one another and can provide “emotional shelter, humour, and communal energy”. Good friendships also take the pressure off a relationship. It’s something she has had to work at throughout her life. When she moved to Washington, Obama made new friends by asking interesting people for their phone numbers and then suggesting lunch or coffee. "There is both richness and safety to be found in other people if you're willing to extend your curiosity that way, if you can keep yourself open to it,” she says. “Your friends are your ecosystem. When you make them, you are putting more daisies in your life. You are putting more birds in the trees.”

How to make a home where people are always glad to see you

One of Marian Shields Robinson’s five pieces of advice relayed by her daughter is that you can’t expect to be liked at work or in public, but: “Come home. We will always like you here.” How lovely to hear that! Fostering that sense of gladness may require change, whether by creating a feeling of home through chosen rather than blood family, or rebuilding spaces and selves, to learn what “being accepted, supported, and loved truly feels like”. That gladness, a lighting up from within, is something that we can offer the world as well as take in return.

The Light We Carry is out now.