- Home |

- Search Results |

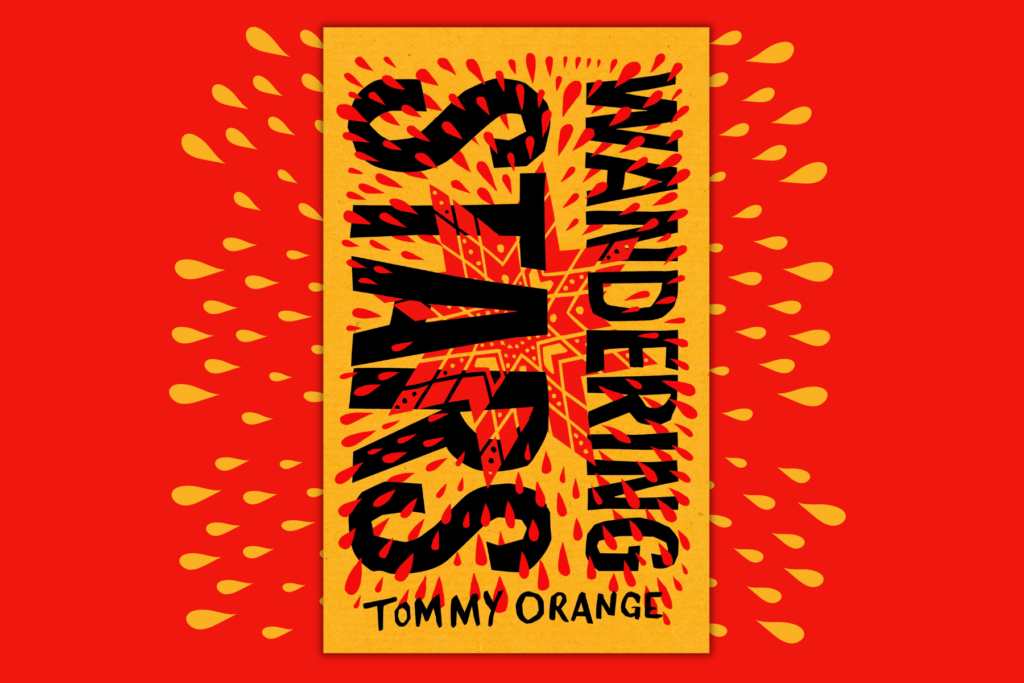

- Extract: Wandering Stars by Tommy Orange

I thought I heard birds that morning time just before the morning light, after I shot up scared of men so white they were blue. I’d been having dreams of blue men with blue breath, and the sound of birds was the slow squeaking of wheels, the rolling of mountain howitzers approaching our camp at dawn. The bad dreams had been coming for weeks leading up to that morning, so I’d taken to sleeping with my grandmother, Spotted Hawk. She’d prayed for me before I closed my eyes to sleep, blew smoke in my face after rolling up some tobacco in a corn husk, then sang me the song that slowed my breath and made my eyelids heavy.

From inside the tipi I thought it was thunder, or buffalo, then I saw the purple- orange dawn light through the holes made by bullets in the walls of the tipi. People outside ran or they died there having been picked off running.

Looking back, everything that happened before Sand Creek once knew my mother’s perfect smile, my father’s crooked one, the way both of their eyes looked to the ground when I made them proud, or cut into me when I made them mad, my brothers’ and sisters’ way of teasing me about my big ears by pulling on my earlobes, or the way they tickled my ribs and made me laugh until I almost cried in that way that made me hate it and love it, but hate it.

Our camp with our animal companions and the big fires we made, the rivers and creeks we played in during summers, or kept away from winters; the hunts I watched the older ones prepare for, how they laughed themselves free when they got back, relieved to have food for everyone, then made

fire and prayed and sang in earnest to the animal and to our Creator God, Maheo.

There were ways to play dead, and come back to life.

Everything that had been before what happened at Sand Creek went back inside the earth, deep into that singular stillness of land and death. At the massacre, while it was happening, the bullets and the screaming, bodies down everywhere, Spotted Hawk shoved a boy at me like: Take him too. I was a young man then, barely not a boy myself. The boy my grandmother pushed at me had freckles spattered around his eyes that looked like blood. If someone had freckles, it usually meant white people had become intimately involved in the lives of one of our people, made some mess. One time, one of my uncles got shot dead right in front of me, some loose white man come to exact revenge shot my uncle in the back of the head, and there splattered on Spotted Hawk’s face was blood patterned just like this boy’s freckles, this boy whose cheeks were full like he’d been saving up spit, like he’d been too afraid to swallow it.

As ever, Spotted Hawk’s face kept whatever she felt behind it. She pointed her lips at a horse, and once we were on, slapped the thing and we were off. When I looked back I saw Spotted Hawk’s body go down. I wouldn’t ever know if it was from a bullet, to take cover, or to play dead. I’d known spiders to do this, had seen a black one with a bright red mark on its belly play dead. I’d hidden and waited, waited and watched, then seen it come back to life just before I came down hard on it with my foot. Years later in Florida, when I first saw the shape of an hourglass, and understood it meant time as the delicate falling of sand through a narrow glass passage, I was reminded of the spider’s mark, and that there were ways to play dead, and come back to life.