- Home |

- Search Results |

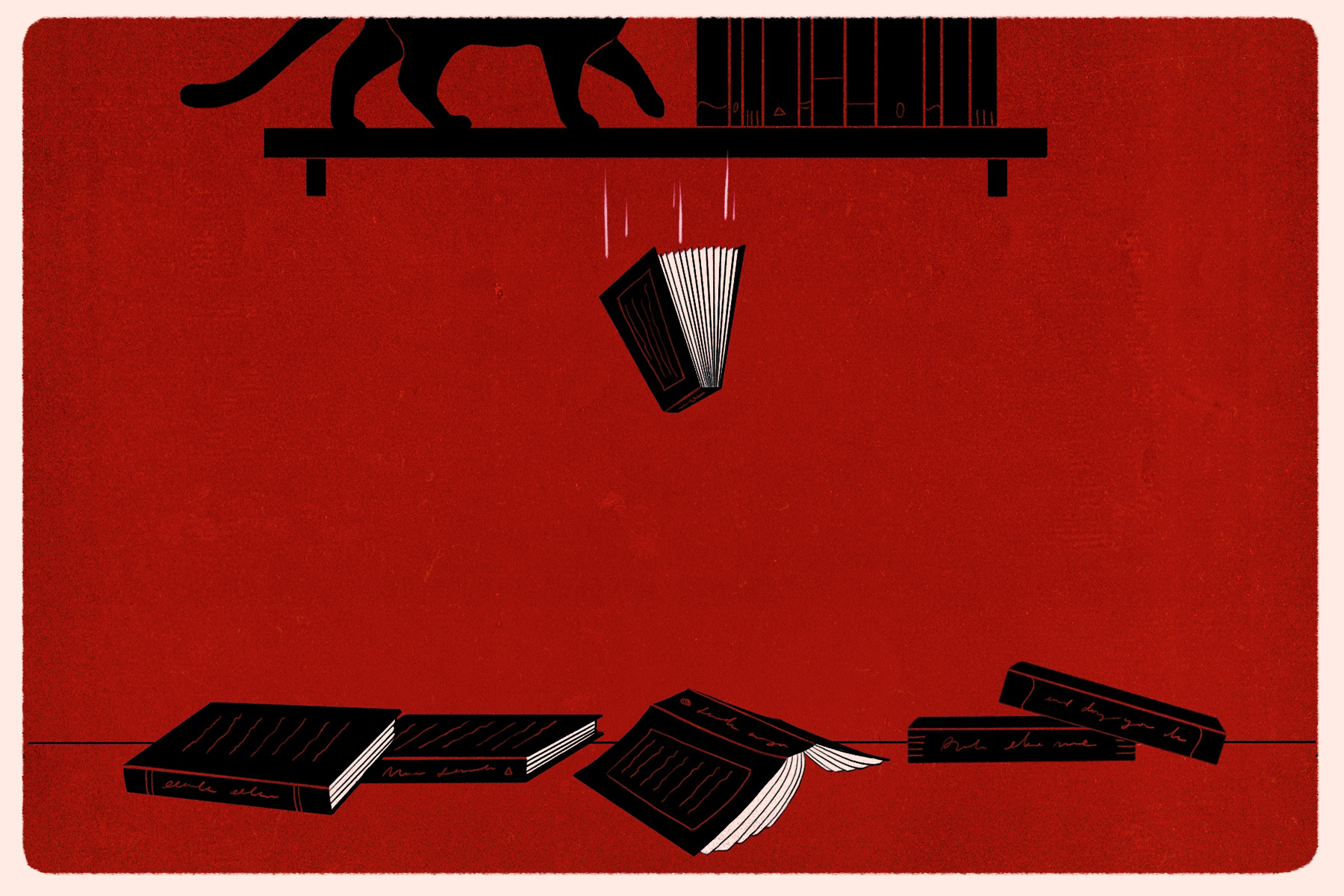

- A short history of literature’s love affair with cats

Many writers have found cats ideal muses, and some have found their lives transformed by them. Patricia Highsmith, who invented the amoral murderer Tom Ripley, found animals – cats in particular – better behaved, and endowed with more dignity and honesty, than most humans. Though she was a brilliant exponent of the psychological thriller, she claimed she would never understand human beings. In one of her short stories, 'Ming’s Biggest Prey', which appears in her collection The Animal Lover’s Book of Beastly Murder, the most vivid character is the cat Ming, who kills his mistress’s lover in revenge for being mistreated.

Perhaps Highsmith simply liked cats more than most of the people she knew. Certainly she praised them for what they gave people like herself. Cats, she wrote, "provide something for writers that humans cannot: companionship that makes no demands or intrusions, that is as restful and ever-changing as a tranquil see that ever moves."

Highsmith is not the only writer of thrillers to have cherished cats. Chester Himes, often considered the father of the Black American crime novel, loved his Siamese cat Griot so much that he went to extreme lengths to obtain food it would eat.

Himes believed the cat would starve to death rather than eat anything he didn’t like. Griot refused tinned cat food, except for a brand called Tabby Treat. When living in Spain Himes wrote to his friend John Alfred Williams asking him to find the address of the company that produced it. Tabby Treat did the trick, and Griot survived.

'Samuel Johnson would walk into town to buy oysters for his black-furred cat Hodge'

The 18th-century English novelist, biographer and lexicographer Samuel Johnson also took great care with his cat’s food. Rather than giving the task to a servant, he would walk into town to buy oysters for his black-furred cat Hodge, and valerian to ease the cat’s pain when it was ill.

Johnson had an unsettled mind and often feared madness. His acquaintance the poet Christopher Smart was confined to an insane asylum for seven years, his only regular companion being his cat, about whom he dedicated a famous poem, 'To My Cat Jeoffry'.

Johnson feared a similar fate. He suffered from depression and anxiety, which he tried to cure by a variety of obsessive-compulsive rituals. When walking in London, he touched every post with his cane; if he missed one, he would start his walk again. He was a great conversationalist and eager for human company. But Hodge seems to have given him something human beings could not – respite from his own thoughts, and thereby from himself.

The American writer Mary Gaitskill, author of the short story on which the 2002 film Secretary was based, adopted a tiny one-eyed cat in Italy, which she called Gattino.

The loss of Gattino affected Gaitskill’s view of love – feline and human –profoundly. Human love she thought was "grossly flawed", often serving as a means of manipulating other people. A recurring theme of Gaitskill’s work is how human beings use love to exercise power over others, to escape boredom and to feel the excitement that can come from being humiliated. Feline love, however, does not have these flaws. A cat loves you if she enjoys your company; if she does not, she leaves. Yet Gaitskill believed her time with Gattino, and somehow even the experience of losing him, enabled her to love the human beings in her life more truly.

A collision between human and feline love is the subject of The Cat, a novella by the French writer Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette in which a lovely Russian Blue cat competes successfully for the love of a newly married young man. Colette too found human love imperfect.

As shown in the 2019 film Collette, where the author is played by Keira Knightley, her first husband exploited her literary talent by publishing a number of novels under his own name. She married again, this time happily, while having several fulfilling long-term relationships with women. Yet she never lost her passion for cats, and lived with them throughout much of her life.

'Not wanting to be anything other than they are, they are calmly content being the cats they happen to be'

Many interpret the human love of an animal as an expression of anthropocentrism – the projection of our own emotions onto other species. With cat-lovers, however, it is not their likeness to us that is adorable but their differences from us. Unlike human beings, cats are by nature happy and do not need to seek respite from being themselves. Not wanting to be anything other than they are, they are calmly content being the cats they happen to be.

This may be the reason human beings, and especially writers, value the company of cats so much. Writing is a solitary business, and the trouble with being alone is that you are never far from your thoughts and anxieties. Cat relish being alone, and yet enjoy being with humans they like. As Collette put it, the secret of cats is that they are necessary to our solitude.