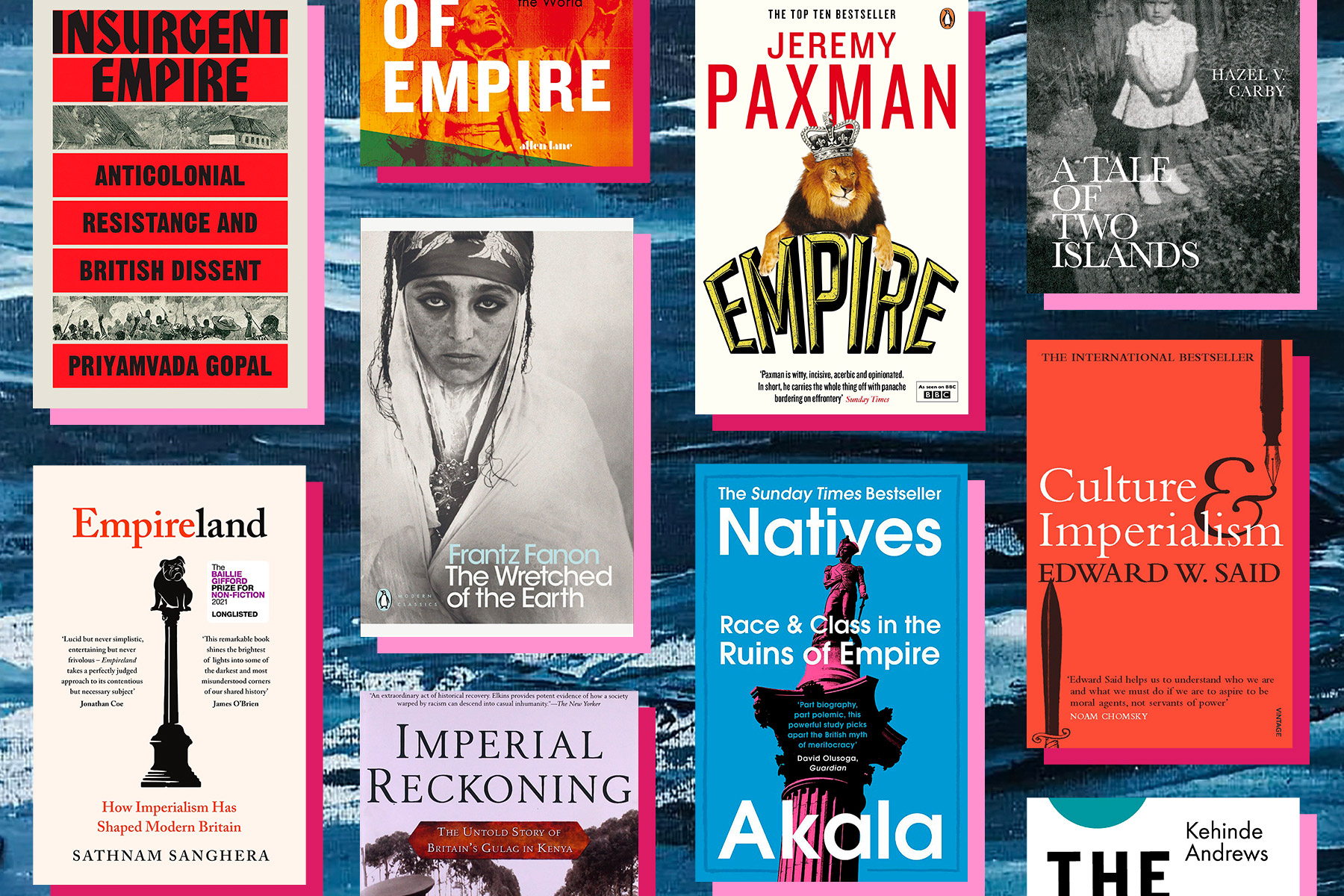

Books to help you understand colonialism

The age of Empire was technically “history” when I was raised around Britain by Iraqi doctors working for the NHS, yet I was always conscious of some lingering colonial spirit. Colonialism remained an undead, shape-shifting force. As a kid, I was distinctly aware of colonial spirit in pop culture – “funny foreigners”, “restless natives” and “swarthy terrorists” were mainstream staples of 1980s and Nineties entertainment – and if you weren’t rooting for the white Western good guys, then what exactly were you?

Growing up, colonial hangovers revealed themselves through British street names, structures and borrowed slang, and certainly through the way that the contemporary world was perceived. When I left Britain to live in Saudi Arabia in my early teens, I found a firmly colonial pecking order in place, with luxurious gated communities for Western “expats” and menial roles for “immigrants” from economically poorer nations such as Indonesia and the Philippines (my Iraqi Shia family resided low-key, on a lower-middle rung).

Later, back in Britain, my answer to that ubiquitous question – “where are you really from?” – went from barely eliciting interest to ringing alarms, when Iraq’s brutal dictator Saddam Hussein (a long-time friend of the West) invaded Kuwait (over a border drawn by Britain in 1922). Iraq became another project for Western intervention, retribution and “liberation” including two shattering Gulf Wars.

What we studied in school – particularly the stultifying lessons of my History A-level – formally detached me from the subject. Meanwhile, everyday events – foreign policies and refugee crises; media reportage from the Windrush scandal to the “War on Terror”; Black Lives Matter movements – continually reminded me of broader narratives around colonialism, racism and Empire.

The increasing range of literature critiquing colonialism surely does not undermine the positive “British Values” (diversity, tolerance) that are now taught in schools, and that are clearly informed by global cultures. The books below are rarely a comfortable read, but they are sharply informed and frequently inspiring, as well as crucially empathetic – after all, an emotional response to colonialism is an entirely human one.

Natives: Race & Class in the Ruins of Empire by Akala (2018)

London hip hop MC and commentator Akala has an assured way with words, like a restless dynamo, and that energy flows onto the page in Natives, which is both lively memoir and multi-layered meditation on Empire and colonialism. Born in the Eighties (“the decade of Thatcherite-Reaganite ascendency”) to a Scottish/English mother and British Caribbean father, Akala uses personal anecdotes to introduce cogent broader arguments, including social and educational assumptions of “Blackness” and constructions of “whiteness”. His boyhood memory of a schoolteacher showing him a portrait of 19th century reformer William Wilberforce and expecting gratitude (because “this man stopped slavery”) spurs much wider considerations: relatively overlooked anti-slavery campaigners (from striking textile workers to Black British abolitionists including Mary Prince Ottabah Cuagano and Olaudah Equiano) and parallels with 21st-century anti-war movements. Quickfire details are distilled throughout into a lucid, invigorating worldview.

Imperial Reckoning by Caroline Elkins (2005)

Shortly after World War II (when thousands of Kenyans had fought alongside British troops to defeat fascism), a movement grew, headed by Kenya’s Kikuyu people, demanding independence from the “British Colony and Protectorate of Kenya”. This was the 1950s Mau Mau uprising; its formation, and the British response – including the detainment, torture and deaths of Kikuyu in “rehabilitation” camps – is the subject of US academic Elkins’s Pulitzer Prize-winning study. The dehumanization of colonial “subjects” is an effective tactic; Mau Mau became synonymous with Western depictions of tribal “savages”, though many British official records of this period were strangely destroyed. Elkins spent a decade travelling, researching and living in rural Kenya to create this devastating work; she does not discount Mau Mau atrocities, but she also gives a vital platform to camp survivors; the accounts of Kikuyu women including Ruth Ndegwa and Esther Muchiri are unforgettably gruelling. Frequently, the images speak for themselves, including the eerily familiar “altruistic” slogan at a detention camp gate: “He Who Helps Himself Will Also Be Helped”.

Insurgent Empire: Anticolonial Resistance and British Dissent (2019) by Priyamvada Gopal

In contemporary news reports, the term “insurgent” feels so heavily loaded; it is conveyed with implicit disapproval (and aligned with terrorism), although it essentially means rebellion against invading forces. In this precise and authoritative study, Cambridge University Professor Gopal explores how rebellions, spanning the 1857 Indian “mutiny” against the British East India Company to the Mau Mau uprising a century later, and how opposition to Empire existed within the “motherland” itself. The dense academic detail makes this involved reading, but it’s also involving and expansive: highlighting alliances (for instance, how Italy’s 1935 invasion of Ethiopia forged pan-African and black anticolonial movements), and organisations, such as the Movement for Colonial Freedom, founded in London in 1954.

Imperial Intimacies: A Tale Of Two Islands (2019) by Hazel V Carby

“Where are you from?” is the repetitive question that spurs writer and academic Hazel V Carby’s extraordinary book, entwining her own family histories while analysing the cultural, political and historical links between the two “small islands” of Britain and Jamaica. Carby, a long-standing Professor of African American and American Studies at Yale, was born in post-war Britain, to a white Welsh mother and a black Jamaican father who had served in the RAF. She writes beautifully, bringing a poetic vivacity to accounts of her ancestral relatives as well as her contemporary encounters. She brings her professional scrutiny to research, including the horrific record books of enslaved humans as colonial “property”; she is diligent in her insights, yet never disengaged, and this is an intensely personal, richly moving and relatable account.

What did you think of this article? Email editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk and let us know.