Why read the classics?

Summary

Let us begin by putting forward some definitions.

1. The classics are those books about which you usually hear people saying: ‘I’m rereading . . .’, never ‘I’m reading . . .’

At least this is the case with those people whom one presumes are ‘well read’; it does not apply to the young, since they are at an age when their contact with the world, and with the classics which are part of that world, is important precisely because it is their first such contact.

The iterative prefix ‘re-’ in front of the verb ‘read’ can represent a small act of hypocrisy on the part of people ashamed to admit they have not read a famous book. To reassure them, all one need do is to point out that however wide-ranging any person’s formative reading may be, there will always be an enormous number of fundamental works that one has not read.

Put up your hand anyone who has read the whole of Herodotus and Thucydides. And what about Saint-Simon? And Cardinal Retz? Even the great cycles of nineteenth-century novels are more often mentioned than read. In France they start to read Balzac at school, and judging by the number of editions in circulation people apparently continue to read him long after the end of their schooldays. But if there were an official survey on Balzac’s popularity in Italy, I am afraid he would figure very low down the list. Fans of Dickens in Italy are a small elite who whenever they meet start to reminisce about characters and episodes as though talking of people they actually knew. When Michel Butor was teaching in the United States a number of years ago, he became so tired of people asking him about Émile Zola, whom he had never read, that he made up his mind to read the whole cycle of Rougon-Macquart novels. He discovered that it was entirely different from how he had imagined it: it turned out to be a fabulous, mythological genealogy and cosmogony, which he then described in a brilliant article.

There will always be an enormous number of fundamental works that one has not read

What this shows is that reading a great work for the first time when one is fully adult is an extraordinary pleasure, one which is very different (though it is impossible to say whether more or less pleasurable) from reading it in one’s youth. Youth endows every reading, as it does every experience, with a unique flavour and significance, whereas at a mature age one appreciates (or should appreciate) many more details, levels and meanings. We can therefore try out this other formulation of our definition:

2. The classics are those books which constitute a treasured experience for those who have read and loved them; but they remain just as rich an experience for those who reserve the chance to read them for when they are in the best condition to enjoy them.

For the fact is that the reading we do when young can often be of little value because we are impatient, cannot concentrate, lack expertise in how to read, or because we lack experience of life. This youthful reading can be (perhaps at the same time) literally formative in that it gives a form or shape to our future experiences, providing them with models, ways of dealing with them, terms of comparison, schemes for categorising them, scales of value, paradigms of beauty: all things which continue to operate in us even when we remember little or nothing about the book we read when young. When we reread the book in our maturity, we then rediscover these constants which by now form part of our inner mechanisms though we have forgotten where they came from. There is a particular potency in the work which can be forgotten in itself but which leaves its seed behind in us. The definition which we can now give is this:

3. The classics are books which exercise a particular influence, both when they imprint themselves on our imagination as unforgettable, and when they hide in the layers of memory disguised as the individual’s or the collective unconscious.

For this reason there ought to be a time in one’s adult life which is dedicated to rediscovering the most important readings of our youth. Even if the books remain the same (though they too change, in the light of an altered historical perspective), we certainly have changed, and this later encounter is therefore completely new.

There ought to be a time in one’s adult life which is dedicated to rediscovering the most important readings of our youth

Consequently, whether one uses the verb ‘to read’ or the verb ‘to reread’ is not really so important. We could in fact say:

4. A classic is a book which with each rereading offers as much of a sense of discovery as the first reading.

5. A classic is a book which even when we read it for the first time gives the sense of rereading something we have read before.

Definition 4 above can be considered a corollary of this one:

6. A classic is a book which has never exhausted all it has to say to its readers. Whereas definition 5 suggests a more elaborate formulation, such as this:

7. The classics are those books which come to us bearing the aura of previous interpretations, and trailing behind them the traces they have left in the culture or cultures (or just in the languages and customs) through which they have passed.

This applies both to ancient and modern classics. If I read The Odyssey, I read Homer’s text but I cannot forget all the things that Ulysses’ adventures have come to mean in the course of the centuries, and I cannot help wondering whether these meanings were implicit in the original text or if they are later accretions, deformations or expansions of it. If I read Kafka, I find myself approving or rejecting the legitimacy of the adjective ‘Kafkaesque’ which we hear constantly being used to refer to just about anything. If I read Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons or Dostoevsky’s The Devils I cannot help reflecting on how the characters in these books have continued to be reincarnated right down to our own times.

Reading a classic must also surprise us, when we compare it to the image we previously had of it. That is why we can never recommend enough a first-hand reading of the text itself, avoiding as far as possible secondary bibliography, commentaries, and other interpretations. Schools and universities should hammer home the idea that no book which discusses another book can ever say more than the original book under discussion; yet they actually do everything to make students believe the opposite. There is a reversal of values here which is very widespread, which means that the introduction, critical apparatus, and bibliography are used like a smoke- screen to conceal what the text has to say and what it can only say if it is left to speak without intermediaries who claim to know more than the text itself. We can conclude, therefore, that:

8. A classic is a work which constantly generates a pulviscular cloud of critical discourse around it, but which always shakes the particles off.

A classic does not necessarily teach us something that we did not know already; sometimes we discover in a classic something which we had always known (or had always thought we knew) but did not realise that the classic text had said it first (or that the idea was connected with that text in a particular way). And this discovery is also a very gratifying surprise, as is always the case when we learn the source of an idea, or its connection with a text, or who said it first. From all this we could derive a definition like this:

9. Classics are books which, the more we think we know them through hearsay, the more original, unexpected, and innovative we find them when we actually read them.

It is no use reading classics out of a sense of duty or respect, we should only read them for love

Of course this happens when a classic text ‘works’ as a classic, that is when it establishes a personal relationship with the reader. If there is no spark, the exercise is pointless: it is no use reading classics out of a sense of duty or respect, we should only read them for love. Except at school: school has to teach you to know, whether you like it or not, a certain number of classics amongst which (or by using them as a benchmark) you will later recognise ‘your’ own classics. School is obliged to provide you with the tools to enable you to make your own choice; but the only choices which count are those which you take after or outside any schooling. It is only during unenforced reading that you will come across the book which will become ‘your’ book. I know an excellent art historian, an enormously well-read man, who out of all the volumes he has read is fondest of all of The Pickwick Papers, quoting lines from Dickens’ book during any discussion, and relating every event in his life to episodes in Pickwick. Gradually he himself, the universe and its real philosophy have all taken the form of The Pickwick Papers in a process of total identification. If we go down this road we arrive at an idea of a classic which is very lofty and demanding:

10. A classic is the term given to any book which comes to represent the whole universe, a book on a par with ancient talismans.

A definition such as this brings us close to the idea of the total book, of the kind dreamt of by Mallarmé. But a classic can also establish an equally powerful relationship not of identity but of opposition or antithesis. All of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s thoughts and actions are dear to me, but they all arouse in me an irrepressible urge to contradict, criticise and argue with him. Of course this is connected with the fact that I find his personality so uncongenial to my temperament, but if that were all, I would simply avoid reading him; whereas in fact I cannot help regarding him as one of my authors. What I will say, then, is this:

11. ‘Your’ classic is a book to which you cannot remain indifferent, and which helps you define yourself in relation or even in opposition to it.

I do not believe I need justify my use of the term ‘classic’ which makes no distinction in terms of antiquity, style or authority. (For the history of all these meanings of the term, there is an exhaustive entry on ‘Classico’ by Franco Fortini in the Enciclopedia Einaudi, vol. III.) For the sake of my argument here, what distinguishes a classic is perhaps only a kind of resonance we perceive emanating either from an ancient or a modern work, but one which has its own place in a cultural continuum. We could say:

12. A classic is a work that comes before other classics; but those who have read other classics first immediately recognise its place in the genealogy of classic works.

At this point I can no longer postpone the crucial problem of how to relate the reading of classics to the reading of all the other texts which are not classics. This is a problem which is linked to questions like: ‘Why read the classics instead of reading works which will give us a deeper understanding of our own times?’ and ‘Where can we find the time and the ease of mind to read the classics, inundated as we are by the flood of printed material about the present?’

This is a problem which is linked to questions like: ‘Why read the classics instead of reading works which will give us a deeper understanding of our own times?’

Of course, hypothetically the lucky reader may exist who can dedicate the ‘reading time’ of his or her days solely to Lucretius, Lucian, Montaigne, Erasmus, Quevedo, Marlowe, the Discourse on Method, Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister, Coleridge, Ruskin, Proust and Valéry, with the occasional sortie into Murasaki or the Icelandic Sagas. And presumably that person can do all this without having to write reviews of the latest reprint, submit articles in the pursuit of a university chair, or send in work for a publisher with an imminent deadline. For this regime to continue without any contamination, the lucky person would have to avoid reading the newspapers, and never be tempted by the latest novel or the most recent sociological survey. But it remains to be seen to what extent such rigour could be justified or even found useful. The contemporary world may be banal and stultifying, but it is always the context in which we have to place ourselves to look either backwards or forwards. In order to read the classics, you have to establish where exactly you are reading them ‘from’, otherwise both the reader and the text tend to drift in a timeless haze. So what we can say is that the person who derives maximum benefit from a reading of the classics is the one who skilfully alternates classic readings with calibrated doses of contemporary material. And this does not necessarily presuppose someone with a harmonious inner calm: it could also be the result of an impatient, nervy temperament, of someone constantly irritated and dissatisfied.

Perhaps the ideal would be to hear the present as a noise outside our window, warning us of the traffic jams and weather changes outside, while we continue to follow the discourse of the classics which resounds clearly and articulately inside our room. But it is already an achievement for most people to hear the classics as a distant echo, outside the room which is pervaded by the present as if it were a television set on at full volume. We should therefore add:

13. A classic is a work which relegates the noise of the present to a background hum, which at the same time the classics cannot exist without.

14. A classic is a work which persists as background noise even when a present that is totally incompatible with it holds sway.

The fact remains that reading the classics seems to be at odds with our pace of life, which does not tolerate long stretches of time, or the space for humanist otium; and also with the eclecticism of our culture which would never be able to draw up a catalogue of classic works to suit our own times.

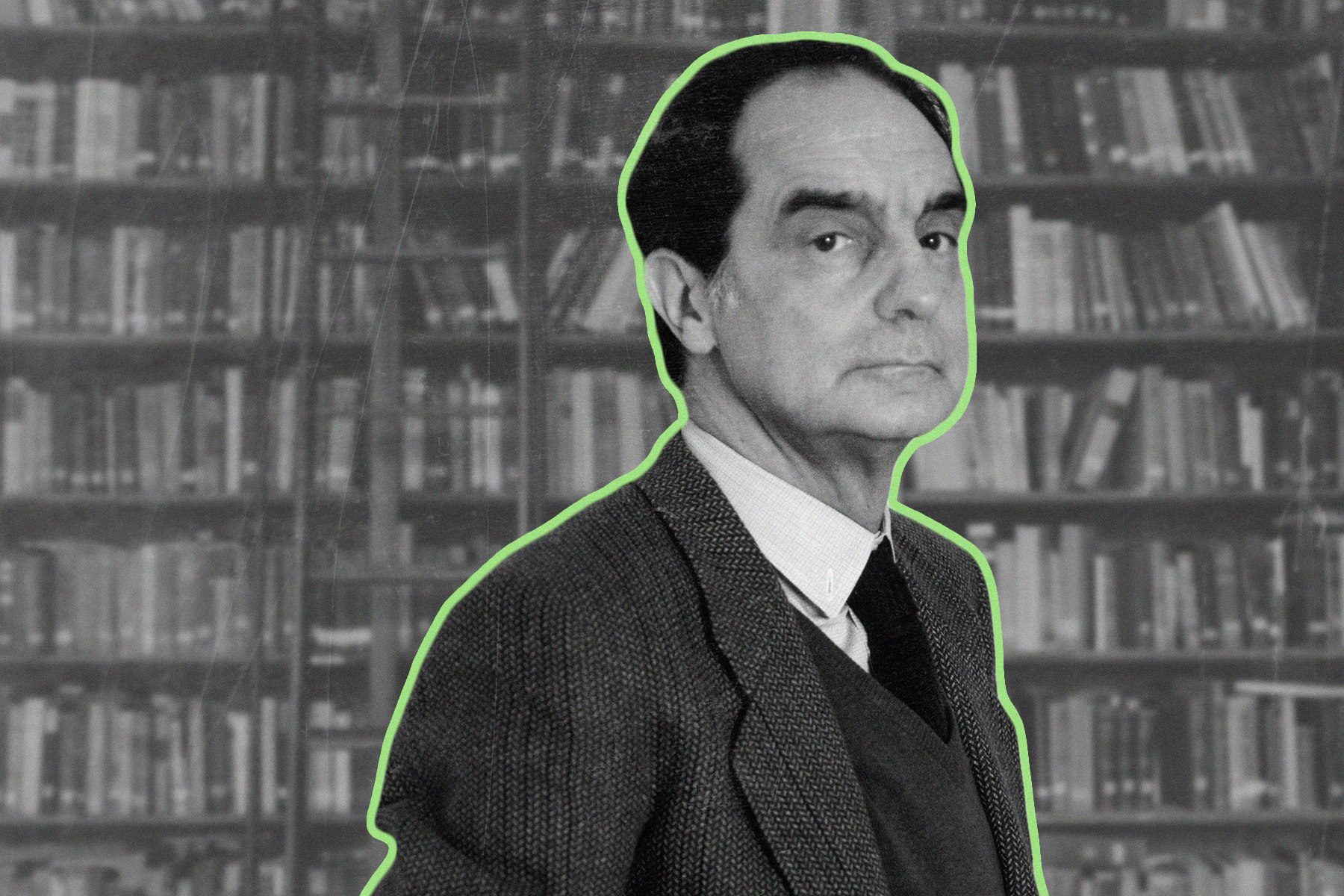

Instead these were exactly the conditions of Leopardi’s life: living in his father’s castle (his ‘paterno ostello’), he was able to pursue his cult of Greek and Latin antiquity with his father Monaldo’s formidable library, to which he added the entirety of Italian literature up to that time, and all of French literature except for novels and the most recently published works, which were relegated to its margins, for the comfort of his sister (‘your Stendhal’ is how he talked of the French novelist to Paolina). Giacomo satisfied even his keenest scientific and historical enthusiasms with texts that were never exactly ‘up to date’, reading about the habits of birds in Buffon, about Frederik Ruysch’s mummies in Fontenelle, and Columbus’ travels in Robertson.

Today a classical education like that enjoyed by the young Leopardi is unthinkable, particularly as the library of his father Count Monaldo has disintegrated. Disintegrated both in the sense that the old titles have been decimated, and in that the new ones have proliferated in all modern literatures and cultures. All that can be done is for each one of us to invent our own ideal library of our classics; and I would say that one half of it should consist of books we have read and that have meant something for us, and the other half of books which we intend to read and which we suppose might mean something to us. We should also leave a section of empty spaces for surprises and chance discoveries.

We should also leave a section of empty spaces for surprises and chance discoveries

I notice that Leopardi is the only name from Italian literature that I have cited. This is the effect of the disintegration of the library. Now I ought to rewrite the whole article making it quite clear that the classics help us understand who we are and the point we have reached, and that consequently Italian classics are indispensable to us Italians in order to compare them with foreign classics, and foreign classics are equally indispensable so that we can measure them against Italian classics.

After that I should really rewrite it a third time, so that people do not believe that the classics must be read because they serve some purpose. The only reason that can be adduced in their favour is that reading the classics is always better than not reading them.

And if anyone objects that they are not worth all that effort, I will cite Cioran (not a classic, at least not yet, but a contemporary thinker who is only now being translated into Italian): ‘While the hemlock was being prepared, Socrates was learning a melody on the flute. “What use will that be to you?”, he was asked. “At least I will learn this melody before I die.”