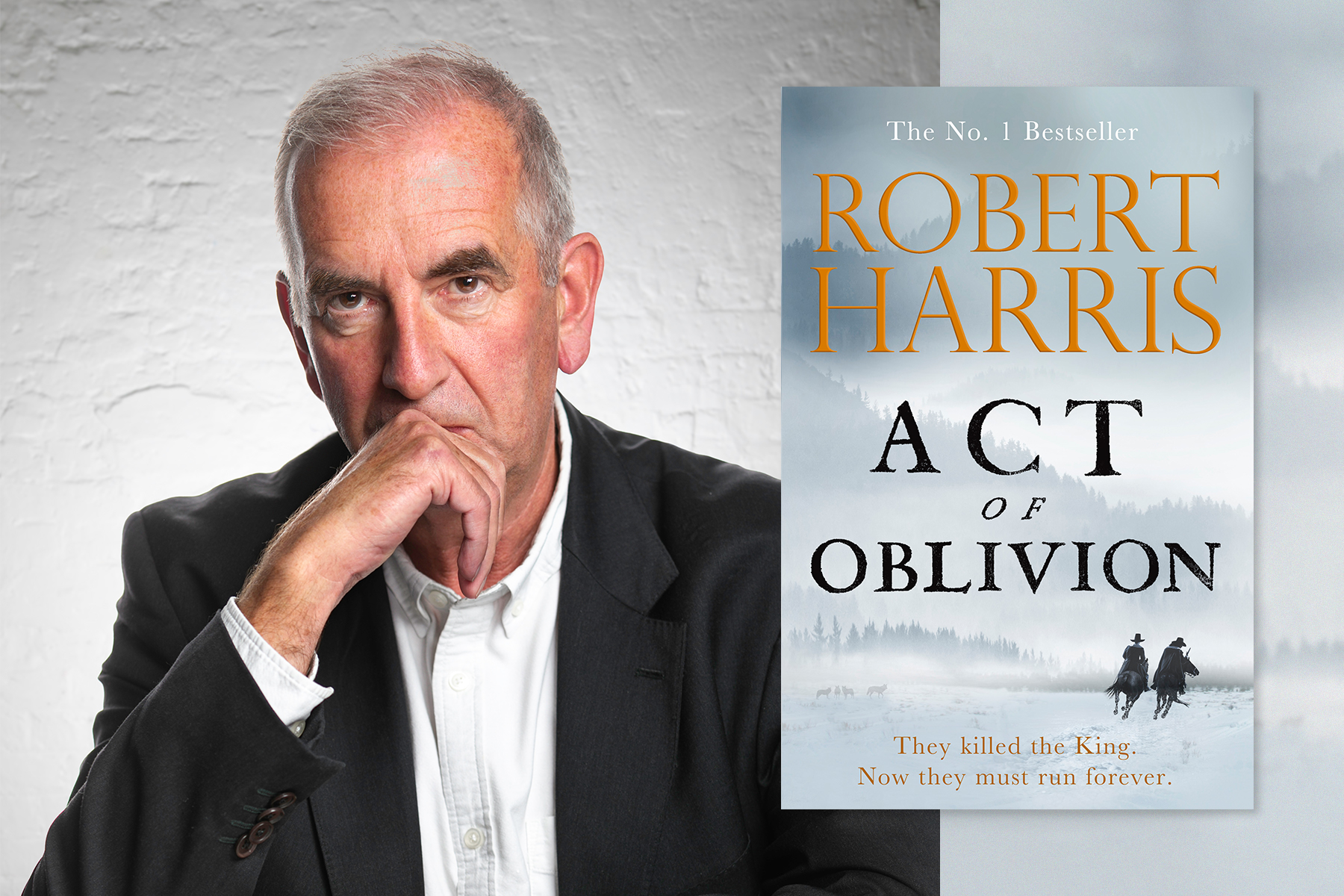

First read: an exclusive extract from Robert Harris’s Act of Oblivion

In September, Robert Harris will release his long awaited novel Act of Oblivion. Today, we’re revealing the book’s cover above, as well as an exclusive extract of its opening chapter, in which a band of fugitives arrive in 17th-century America with a murderous secret…

1

IF YOU HAD SET OUT in the summer of 1660 to travel the four miles from Boston, Massachusetts, to the village of Cambridge, the first house you would have come to after crossing the Charles River would have been the Gookins’.

It stood beside the road on the edge of the settlement, midway up the marshy land between the river and Harvard College – a confident, two-storeyed timbered property in its own fenced lot with an attic in its steep roof commanding a clear view of the Charles. In 1660 the colony was still building its first bridge across the river. Great wooden piles had been driven into the mud close to the ramp where the ferry boat ran, and the sound of hammering and sawing and the shouts of the workmen carried all the way up to the house on the drowsy midsummer air.

On this particular day – Friday 27 July – the front door was flung wide open and a childish sign reading ‘Welcome Home’ had been nailed to the gatepost. A ship from London, the Prudent Mary, was reported to have dropped anchor that morning between Boston and Charlestown. Among her passengers was believed to be Mr Daniel Gookin, the master of the property, returning to America after an absence of two years.

Once the news of the ship’s arrival reached Cambridge, the house, which had been spotless to begin with, had been freshly swept and tidied, the children scrubbed and forced into their best Sabbath clothes. By early afternoon all five were sitting waiting with Mrs Gookin in the parlour: Mary, who was twenty and named after her mother; Elizabeth, who was eighteen; and their three younger brothers, Daniel Jr, ten, Samuel, eight, and four-year-old Nathaniel, who had no memory of his father, being unable even to speak at the time of his departure, and who was fidgeting in his chair.

Nat’s eyes widened. ‘If he’s dead then who will protect us?’

Yes, that would be it. She could see it clearly: the shrouded body, the ship’s company assembled, the brief prayers, the corpse weighted at the neck sliding head-first down the gangplank and into the waves. It had happened twice on their original voyage from England nearly twenty years before.

‘Go outside, boys, and wait for him there.’ Nat scrambled off her lap and all three darted for the door like cats released from a sack. ‘But don’t dirty your clothes!’

The girls remained in their places. Mary, who was most like her mother in her stolid good sense, and who had acted the man’s role in the household over the past two years, said, ‘I’m sure there’s no need to worry yourself, Mama. God will have protected him.’

But Elizabeth, who was prettier than her sister and who grumbled about her chores, burst out, ‘Yet it must be seven hours since his ship arrived, and it is only an hour from Boston!’ She folded her arms in irritation.

‘Lizzy, don’t question your father’s actions,’ chided Mrs Gookin gently. ‘If he is delayed, he will have good reason.’ And if it turns out he isn’t in Boston – But before she could complete the thought, Daniel called from outside: ‘Someone’s coming!’

Daniel called from outside: ‘Someone’s coming!’

They hurried out of the house, through the little gate and on to the dried rutted mud of the road where Mrs Gookin squinted in the direction of the river. Her eyesight had worsened since her husband had been away. All she could make out was the dark blur of the ferry halfway across the glittering water. But the boys were shouting, ‘It’s a cart! It’s a cart! It’s Papa in a cart!’ And they dashed down the road to meet it, Nat’s short legs pumping to keep up with his brothers.

‘Is it really him?’ asked Mrs Gookin, peering helplessly.

‘It’s him!’ cried Elizabeth. ‘See – look – he’s waving!’

‘Oh, thank God!’ She fell to her knees. ‘Thank God!’

‘Yes, it’s him,’ repeated Mary, shielding her eyes from the sun, but then she added, in a puzzled voice, ‘and he has two men with him.’

•

In the immediate flurry of kisses and embraces, of tears and laughter, of children being tossed into the air and whirled around, the pair of strangers, who remained throughout politely seated in the back of the cart among the luggage, were at first ignored.

The pair of strangers, who remained seated in the back of the cart among the luggage, were at first ignored

Daniel Gookin hoisted Nat up on to his shoulders, tucked Dan and Sam under either arm and ran with them around the yard, scattering the chickens, then turned his attention to the shrieking girls. Mary had forgotten how big her husband was, how large a presence. She could not take her eyes off him. Finally, Gookin set down the girls, placed his hand around Mary’s waist, whispered, ‘There are men here you must meet; do not be alarmed,’ and ushered her towards the cart. ‘Gentlemen, I fear I have plain forgot my manners. Allow me to present my wife, the true Prudent Mary – in flesh and blood at last!’ A pair of weather-beaten, ragged-bearded heads turned to examine her and hats were lifted to reveal long, matted hair. They wore buff leather overcoats, caked with salt, and high-sided scuffed brown boots. As they stood, somewhat stiffly, the thick leather creaked and Mary caught a whiff of sea and sweat and mildew, as if they had been fished up from the bed of the Atlantic. ‘Mary, these are two good friends of mine, who shared the crossing with me – Colonel Edward Whalley and his son-in-law, Colonel William Goffe.’

Whalley said, ‘Indeed a pleasure to meet you, Mrs Gookin.’

She forced a smile and glanced at her husband – colonels? – but already he had withdrawn his hand and was moving forward to help them down from the cart. She noticed how deferential he was in their presence, and how when they put their feet to the ground after so many weeks at sea, both men swayed slightly, and laughed, and steadied one another. The children gawped.

Colonel Goffe said, ‘Let us give thanks for our deliverance.’ Beneath his beard he had a fine, keen, pious face

Colonel Goffe said, ‘Let us give thanks for our deliverance.’ Beneath his beard he had a fine, keen, pious face; his voice carried a musical lilt. He held up his hands, palms flat, and cast his eyes to the heavens. The Gookin family quickly wrenched their gaze from him and lowered their heads. ‘We remember Psalm

one hundred and seven: “Oh that men would praise the Lord for his goodness, and for his wonderful works to the children of men! They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters; these see the works of the Lord, and his wonders in the deep.” Amen.’

‘Amen!’

‘And who do we have here?’ asked Colonel Whalley. He moved along the line of children, collecting names like an officer inspecting his men. At the end, he pointed to each in turn. ‘Mary. Elizabeth. Daniel. Samuel. Nathaniel. Very good. I am Ned, and this is Will.’

Nathaniel said, ‘Did you know the Lord Protect Her, Ned?’

‘I did, very well.’

‘He is dead, you know.’

‘Hush,’ said Mrs Gookin.

‘Aye, that he is, Nathaniel,’ replied Ned sadly, ‘more’s the pity.’

Mary Gookin had nursed a hope that her husband had merely offered the two men a ride. Now, she felt dismay

There was a silence.

‘Boys,’ said Mr Gookin, ‘fetch the colonels’ bags for them.’

Until that moment, Mary Gookin had nursed a hope that her husband had merely offered the two men a ride. Now, as she watched them unload their luggage from the cart and hand it to her sons, she felt dismay. It was hardly the homecoming she had dreamed of all those months – to feed and shelter two senior officers of the English army.

‘And where are we to put them, Daniel?’ She spoke quietly so they could not overhear, and took care not to look at her husband, the easier to keep her temper.

‘The boys can give up their beds and sleep downstairs.’

‘How long are they to stay?’

‘As long as it is necessary.’

‘What is that? A day? A month? A year?’

‘I cannot say.’

‘Why here? Are there no rooms to be had in Boston? Are the colonels too poor to pay for their own beds?’

‘The Governor believes that Cambridge is a safer lodging-place than Boston.’

Gookin took a while to reply. By the time he spoke the men had gone inside. He said quietly, ‘They killed the King'

‘You have consulted the Governor about this matter?’

‘We have been with him half the day. He gave us dinner.’

Dinner. So that is why his journey from Boston has taken him so long. She watched the boys struggling under the weight of the large bags, the two colonels walking behind them towards the house, talking to the girls. To her feelings of dismay and now irritation was suddenly added an altogether sharper emotion: fear.

‘And why,’ she began hesitantly, ‘why does the Governor say that Cambridge is “safer” than Boston?’

‘Because Boston is full of rogues and royalists, whereas here they will be among the godly.’

‘They are not visitors from England, then, so much as – fugitives?’ He made no answer. ‘From what is it they flee?’

Gookin took a while to reply. By the time he spoke the men had gone inside. He said quietly, ‘They killed the King.’