What is the ideal chapter length?

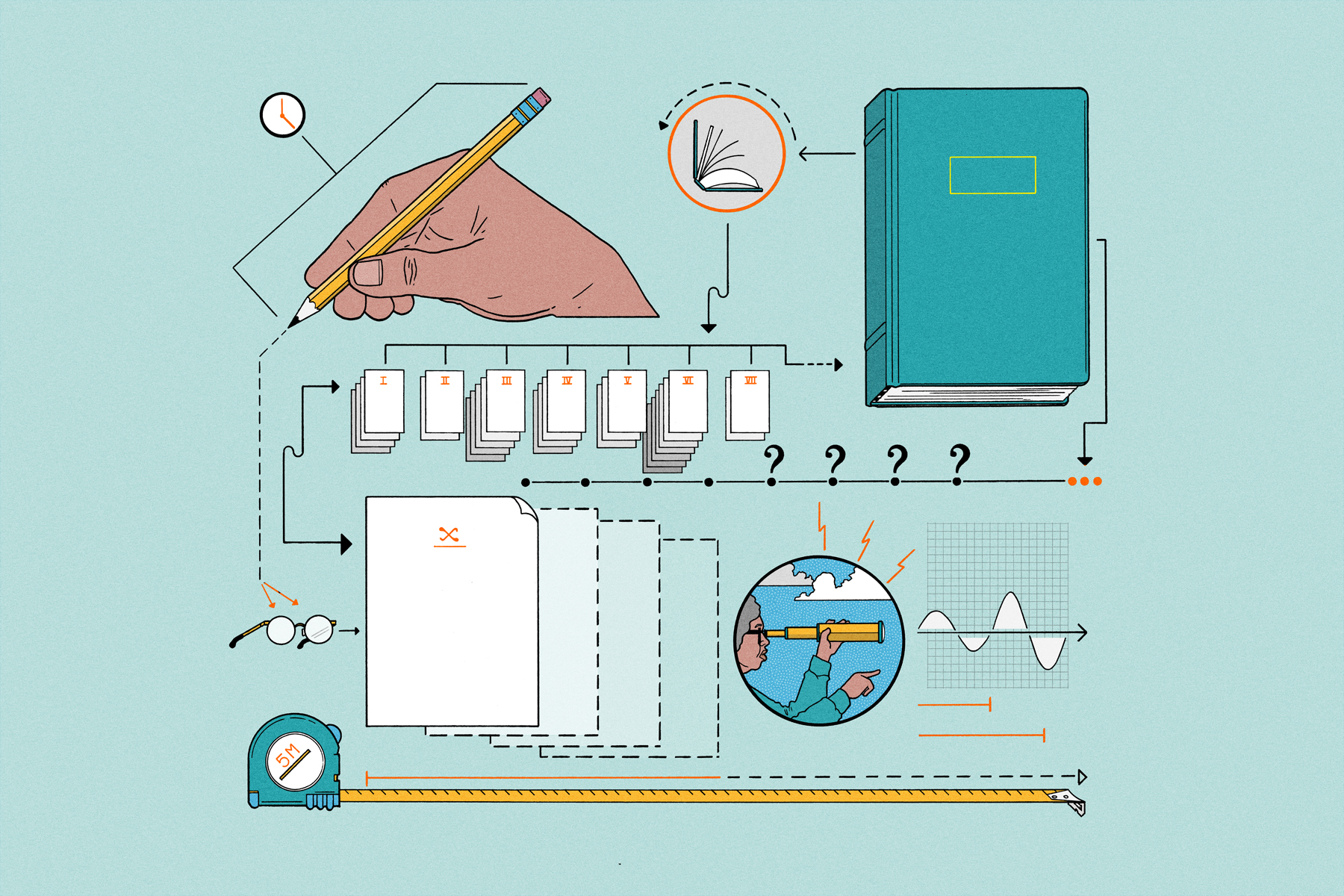

Whether it's shortened for today's distracted reader, or written long, the chapter's 2000-year history is full of variations, trends, and surprises.

In November 2022, a BookTok member reading Donna Tartt’s debut novel, The Secret History, asked, "Why did no one warn me about how long these chapters are? Over 600 pages and it’s only 8 chapters? Disgusting". Yes, they were being deadpan, but also, yes – we’re going through a period with a vogue for short chapters.

Published thirty years before, Tartt's bestseller falls into the dark academia trend that has enchanted readers on TikTok (you could argue it created it), but its 576 pages are divided into eight chapters – a fairly punchy ask for readers increasingly used to short, or what some book marketers call 'potato chip', chapters: snacky, addictive sections of around 2000 words that keep the reader coming back for more.

You could credit TikTok or the impact of the pandemic on this reduction in attention span. However, it may simply be the case that the only consistent thing in life is change. In the 18th Century, your average chapter length was around 1500 words; by the 19th Century, it was more like 3500.

Where did book chapters originate?

Chapters began over 2000 years ago as a feature of what we might now term non-fiction and miscellanies. Divided by number, these breaks in text offered an aide-memoire for a reader whom the author ruefully acknowledged would not be reading the entire thing but dipping in and out for specific information. Such divisions made it easier to remember where the gold was to be found.

What proved helpful for information proved less so for narrative. Ancient and medieval writers working with the Bible tried numerous different ways of dividing up the text, each at the mercy of what the editor decided to be the most important element and thus the name of that part. The Parisian scholars of the early 13th Century could not abide such chaos, and so a standardised chaptering of the Bible was developed, dividing the book into regular sections themed by time and place while still adhering to key moments.

The origin of the name came from the Latin word ‘capitulum’, which became 'chapter' in English. The Bible translator Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus (mercifully also known simply as ‘Jerome’), who first translated the Hebrew Bible into Latin between 382 and 405, is thought to be the first person to use that term, and ‘index capitulorum’, which we would now think of as a table of contents.

While the need for chapters to break up information seems straightforward, why would fiction need them? In his excellent 2014 essay for The New Yorker, The Chapter: A History, Nicholas Dames describes its impact thus: "What the chapter did for the novel was to aerate it: by encouraging us to pause, stop, and put the book down—a chapter before bed, say—the chapter-break helps to root novels in the routines of everyday life."

Chapters in the 18th Century

As Dames said, authors would themselves gently explain to their reader why such a pause might be useful. In Henry Fielding’s 1742 novel, Joseph Andrews, Fielding described “those little Spaces between our Chapters” as “an Inn or Resting-Place, where he may stop and take a Glass, or any other Refreshment, as it pleases him.”

This didn’t mean that authors always took their chapters seriously. Jonathan Swift’s 1704 satire, A Tale of a Tub, features numerous digressions, including a ‘Digression in Praise of Digressions’, with instructions from the author to cut out and replace the chapter elsewhere in the book should the reader so desire. In The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, Laurence Sterne used his chapters as visual underlinings, leaving a full page of chapter 38 blank for the reader to 'paint to mind' the comely widow Wadman, and leaving chapters 18 and 19 entirely blank, only to be filled in once the reader has completed chapter 25.

Chapters in the 19th Century

The episodic nature in which some novels were delivered, such as Charles Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers and George Eliot's Middlemarch, both released in monthly instalments, brought in cliffhanger endings and an increased sense of adventure. Chapter titles often carried a mini summary of what was about to happen, in the style of a breathless envoy enticing the reader to keep going. Later novels of the 19th Century balked against this trend, with shorter, often one-word titles becoming more common.

It was a fabulous way of building a loyal audience and keeping them on side, and it meant that reading fiction became affordable, too: while the cost of a book had dropped by forty per cent between 1828 and 1853, that was still from a very high starting price. Most novels around Dickens' time sold less than five hundred copies, which made his own sales so extraordinary - 800,000 copies of the book form of The Pickwick Papers by 1879, significantly helped by the serialisation.

While he wrote much of his earlier work for the weekly reader, Dickens preferred monthly instalments, which allowed him to use "the large canvas and the big brushes", as he put it. The nature of being so close to his readers (and writing as he went, albeit to a well-planned structure) meant that their responses could shape the narrative. Dombey and Son's Walter Gay was originally intended for a miserable end, but reader response meant Dickens changed this to a happy one.

Chapters in the 20th Century

As the chapter has become engrained in the construction of fiction, authors have found ways to play with it still further, whether by using the titles or numbering structure to underline elements of character or subject, or themes within the book. The horrors of the First World War, and the many deaths that came as a result, led to literary as well as social rejection of the status quo, and unreliable narrators. Virginia Woolf divided her stream-of-consciousness novel, Mrs Dalloway, into twelve sections rather than chapters, each representing an hour in the day. James Joyce divided Ulysses into three books and 18 'episodes' that match up loosely with the 24 in Homer's The Odyssey. These episodes did not have chapter headings or titles, although Joyce named them in his letters.

Using chapter titles and contents to play with the form was by no means a new feat, though. Lewis Carroll underlined the fantastical nature of 1871's Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There with rhyming titles for his late chapters 'Shaking' (contents of which just over 50 words) and 'Waking' (seven: "—it really was a kitten, after all."). The rise of metafiction and the general playfulness of postmodernist literature took this to new heights. Flann O'Brien's At Swim-two-birds begins with 'Chapter 1' and never mentions chapter structure again. Conversely, Kurt Vonnegut used 127 chapters for his Cold War satire Cat's Cradle – most a page, some only a sentence, all ending with a punchline.

Chapter length today

Chapter structure has also been used to emphasise the author's themes. For The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, the hero of which is a mathematical adept with autism spectrum disorder, Mark Haddon used prime numbers to title the chapters. Cormac McCarthy eschewed a chapter structure altogether for his 2006 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Road, to emphasise the gruelling journey being undertaken by his father and son lead characters through post-apocalyptic America.

With our phones offering us immediate dopamine, books now have to work harder to keep us engaged. 'Busy-ness' has become an increasing distraction, through work and parenting as well as social media. That's why you may have noticed shorter chapters in more recent books, especially ones aimed at readers of millennial age and below (that's pretty much everyone under forty).

As any writer will find, however, there is no magic button when it comes to chapter length: the 'right' one is a blend for each novel being written. There's no point in worrying about the length of your piece of string if the string itself isn't useful or compelling.